About the Book

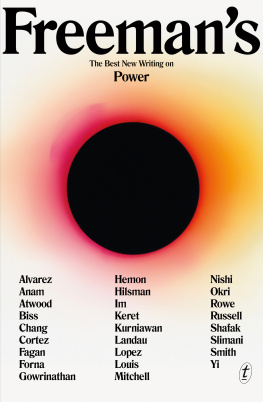

Freemans: Power

From the voices of protestors to the encroachment of a new fascism, everywhere we look power is revealed. This thought-provoking issue of the acclaimed literary anthology Freemans explores who gets to say what matters in a time of social upheaval.

Margaret Atwood posits its time to update the gender of werewolf narratives. Aminatta Forna shatters the silences which supposedly ensured her safety as a woman of colour walking in public space. Meanwhile, the hero of Tahmima Anams story achieves freedom by selling bull semen. Josephine Rowe recalls a gallery attendee trying to take what was not on offer when she worked as a life-drawing model. Booker Prize winner Ben Okri watches power stripped from the residents of Grenfell Tower by ferocious neglect.

Featuring the work of new writers Nicole Im, Jaime Cortez and Nimmi Gowrinathan, as well as some of the worlds best storytellers, including Tracy K. Smith, Alexsandar Hemon and Elif Sharak, Freemans: Power escapes from the headlines of today by going to the heart of the issue.

Contents

When I was a child, I had an obsession with speedometers. I rode around on my bike peering in one driver-side window after another, noting the top speed of all the neighbors cars. This was the late 1970s during the gasoline crisis, so a lot of dials topped out at 75 or 85 mph. Even the font used for these numbers seemed apologetic, and serious, like it was actually saying, You really shouldnt be going this fast. Older and foreign cars provided more thrills. I still feel the shock of looking into a 1955 Chevy and seeing 120 on the gauge. I tooled home for dinner, that miraculous number turning in my head.

Back then my own top speed was around 14 mph, so these numbers were more than trivia. They were a kind of imagined agency. Every single thing I loved back then had some form of locomotive agency. It pierced the earths atmosphere or burned a stripe of rubber at the drag strip or unzippered a lakes calm. I moved significantly only when an adult decided I should. I didnt envy the drivers of fast and powerful things, I envied the vehicles themselves. My dream was to be a truck driver. How wonderful it would be, I thought, to have a strapping friend to explore the world in, sleep in at night, talk to as miles peeled by.

Eventually, I got my chance. In 1984, my family moved to California. A trucking van not much smaller than our house parked outside and men shoved all our worldly belongings into its mouth. We set off in our tiny brown station wagon across the country, and Koolas the stenciled door of his big rig announced himfollowed behind. The plan was to stop every 800 miles or so with a friend or family member, see the country. My father was forty-five years old that year, older than I am as I type this. I try to imagine what it would be like to start my life over with three children and nothing but the anchor of a new job that could go badly, and I marvel.

We arrived in Sacramento a day before Kool, who parked his truck beneath our enormous new palm tree. I climbed into his cab as my grandfather, uncle, and father talked. I was bewildered by the big rigs gauges, amazed by the height of its ride, and confused by how the truck seemed to be floating, almost going backward. In fact, it was: Id depressed an air brake, and four tons of moving van had begun rolling toward the men unloading it. Kool hopped up into the truck in a single bound, and shoved me aside. Look out man, he shouted, youre going to kill someone. My uncle, who had always spoken to me as if I were an equal, took me aside afterward, knelt down, and said the same. This could have been a terrible day.

Those words haunted me upon our arrival in California. Partly because I knew, in some obscure fashion, that I was drawn into that truck by a feeling of powerlessness. Id spent three weeks trapped in our family car, carted across the country, not much freer than the family dog, watching as people freer than me went about their adventures. I wanted power like theirs. I was tired of imagining it; the time had come for me to have some for myself. I didnt think I was actually going to drive away in Kools rig, but I wanted to know what itd feel like. Sort of like holding an unloaded gun.

In light of the possible consequences, this desire seemed suddenly to me like a form of greed. It made me ashamed, and it would later dawn on me that all around forked other forms of power. The power of my imagination, to envision the horror scene Kool had very barely averted; the power of my fathers forgiveness, which washed over me days later like the cool of a cloud stepping in front of the sun; the power of the sun itself, bolting down on us in Sacramento, even in the fall, erasing in all its yellow light the past just like that; and the power of love, which I felt from my grandmother whom wed left behind. I could see her sitting at her writing desk, the lake we used to visit behind her. To feel her warmth from such a distance merely from her letters? That was a power. Everything that was, I discovered, was enacted by power. Having power meant nothingit was valuable depending on how you deployed it.

It says something that in our current political context, an issue of Freemans themed to power may come trailed by an expectation that this will be an issue about the flagrant and breathtaking abuses of power ongoing right now across the globe. I thought of doing this. We are indeed living in a time of power grabbing, of economic sadism, which is to say violence. And there has been precious little leadership from people who possess the greatest power. At the time of this writing, the president of the United States is not unlike a little boy who has climbed up into a huge truck hes always wanted to possess. And already he has run over people. He doesnt even care.

One of the degradations of the recent period, though, is how abuses of power can reduce our definition of power itself. The abiding fantasy of so many, after all, myself included, is to expose corrupt leaders and this current president. To bring them lower than theyve brought people they abused. This is a fantasy like jumping into the truck, though. There are so many other vectors of power slicing through life, from the power of generosity to the power of taking over ones story, and it is this enlarged sense of what power isnot just the power to take, or to dominatewherein lies our salvation.

In this sense, the issue of Freemans you hold in your hand is an attempt to look at how power operates in the world. And I hope it simultaneously recalibrates the balance of power through that observation. I see you, many of these pieces say; I see you seeing me, and heres what youre missing. In her ferocious essay, Aminatta Forna describes all the ways being a woman of color on the street requires constant vigilance regarding how power is being used to frame her. She speaks back. She looks back. Shes tired of having to assess when those actions are dangerous.

Violence lurks within the frame of every single one of these pieces. Growing up in Israel, Etgar Keret learns that the willingness to inflict harm is a great form of powersomething the hero of Eka Kurniawans story grapples with, too. In her startling essay on suicide, Nicole Im turns to the behavior of sharks to meditate on how a willingness to stop pain by turning it on oneself does not necessarily mean freedom. In her poem, Update on Werewolves, Margaret Atwood sees a need to update the horror genre for a world in which women have more power than before, and that danger exists when any power runs amok.

Next page