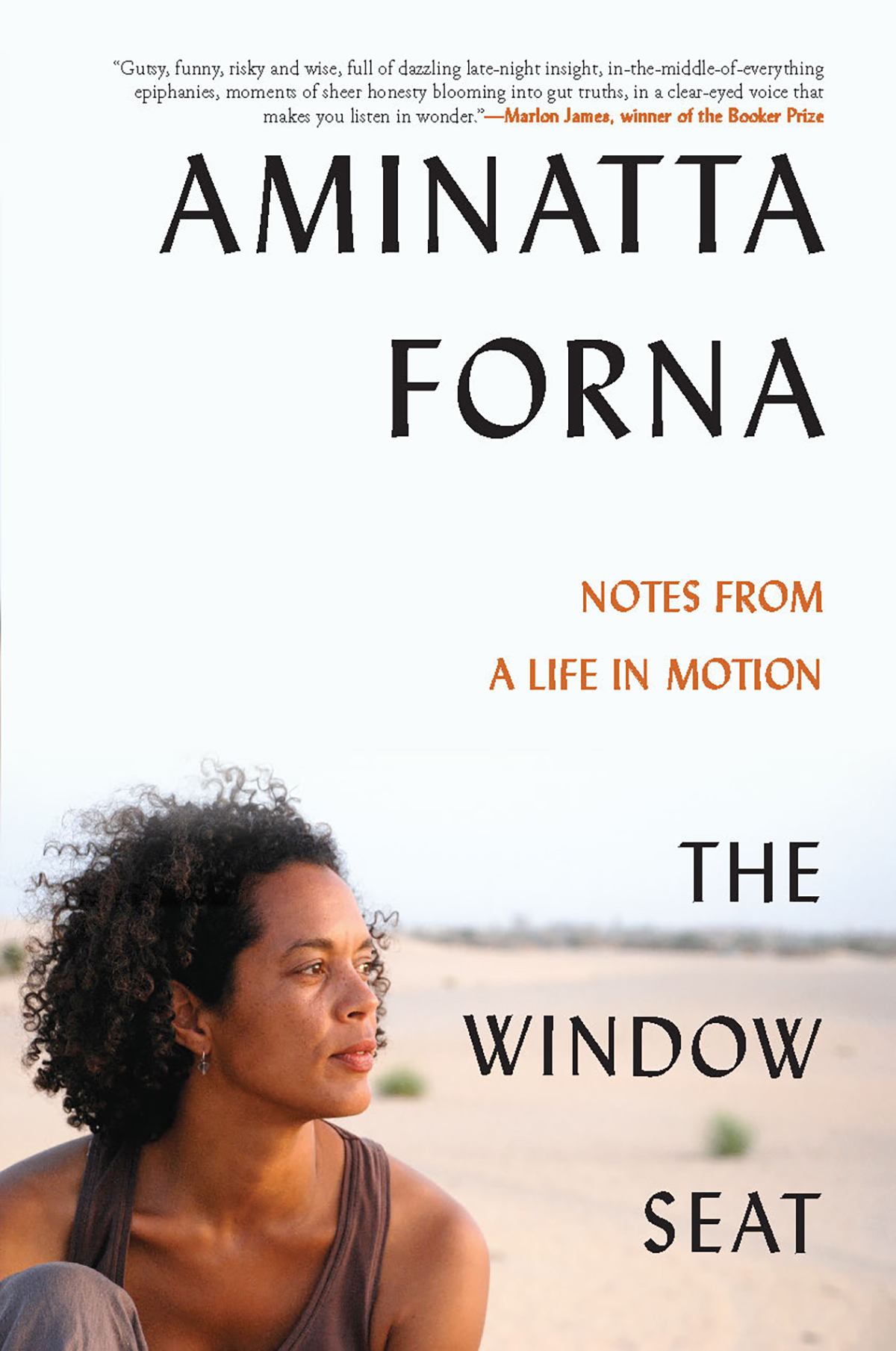

THE WINDOW SEAT

Also by Aminatta Forna

Happiness

Ancestor Stones

The Memory of Love

The Hired Man

The Devil That Danced on the Water

AMINATTA FORNA

NOTES FROM A LIFE IN MOTION

THE WINDOW SEAT

Grove Press

New York

Copyright 2021 by Aminatta Forna

Jacket design by Kelly Winton

Jacket photograph John Christie

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of such without the permission of the publisher is prohibited. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated. Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or anthology, should send inquiries to Grove Atlantic, Inc., 154 West 14th Street, New York, NY 10011 or .

Published simultaneously in Canada

Printed in the United States of America

First Grove Atlantic hardcover edition: May 2021

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is available for this title.

ISBN 978-0-8021-5858-1

eISBN 978-0-8021-5859-8

Grove Press

an imprint of Grove Atlantic

154 West 14th Street

New York, NY 10011

Distributed by Publishers Group West

groveatlantic.com

For Maureen Campbell White

Contents

Here are four words you rarely hear these days: I love to fly. I do. Im talking about being a passenger on a commercial flight. Whatever emotions attend the journey, whether I am flying for work or pleasure, towards loved ones or away, once in my seatespecially if I am alone and have managed to secure myself a window seaton seeing the marshaller signalling the plane with orange batons like a tamer before a recalcitrant circus beast, a feeling of ease comes over me. This remains true after the hundreds of flights I have taken. I love the drama of the take off. The improbability of the whole endeavour. A cat jumping is a reversal of gravitythe cat seems to pour itself upwards. An aeroplane is more like a galloping draught horse that, through sheer determination, somehow succeeds in clearing the oncoming fence. Having completed its ponderous journey to the runway, the plane turns its nose to face the long stretch of tarmac. Then comes the bellowing of the engines spooling up. The plane begins to move, slowly at first and then faster, faster. I can judge to the second the moment the nose will lift, the wheels leave the tarmac and we shudder into the air. The plane rises, dips and turns in a new quiet.

In 1967 I took my first flight, of which I remember nothing. I travelled with my mother, sister and brother. We were leaving behind Sierra Leone and my father on our way to my mothers family in Scotland. My father was a political activist, and the mood in the country was taut. He had been arrested, detained and released, but now he was being followed wherever he went. Between them, my parents had decided my mother should leave and take us with her. It would be a year before we saw our father again. Sudden departures and arrivals punctuated my childhood. Looking back, flying and fleeing often amounted to the same thing. Though I was too young in those early days to feel the tension and sadness such departures would one day evince, I imagine I was aware, in some peripheral way, of the drama of our departure, the packing of suitcases, the ferry ride to the airport.

In quieter times we came and went on holiday from school in England, flying without the comfort of either parent. We were unaccompanied minors, which in those days carried a different quality of meaning to that which it does now. I was the owner of a Junior Jet Club member logbook in which I recorded all my flight miles with a fountain pen, which the cabin pressure would cause to leak and so I frequently arrived covered in ink. Id hand my book to the stewardess (they were all stewardesses in those days), who would carry it forward to be signed by the captain. Sometimes, if we were lucky, the captain would invite us into the cockpit. We would walk the length of the plane in pairs, escorted by a hostess like tiny VIPs.

There in the cockpit, flying felt as effortless as sailing; the plane carried the weightlessness of a boat in water. And whereas the windows in the passenger sections were small and dull, here the sky reached out in all directions, a sensation I have only ever had in the widest of landscapes, in the Australian desert or standing before the view from the Bandiagara Escarpment in Mali. In such places the sky is godlike. To fly is to be enfolded into that power. You can do nothing but fall silent. Swimming is as close as humans get to the sensation of flying as birds do. Once, scuba diving, I swam over the edge of an underwater cliff, and below me the seabed fell away some thousand or more feet. Although I was no deeper and in no danger, I felt suddenly afraid and swam back to where I could see the ocean floor.

A few months ago, I was in Heathrows Terminal Three, and I passed a place so familiar it put a sudden squeeze on my heart. A staircase, an empty space, the marbled floor of the terminal building, that was all there was to it. It took me a moment to realise what was missing: a cordon, maybe six or eight chairs in rows facing another chair upon which an air hostess sat. This was the place where we, the unaccompanied minors, waited to be escorted to our gates. Now the cordon and chairs are gone, the carriers who operated the international flights out of Britain, BOAC (British Overseas Airways Corporation) and British Caledonian (which flew out of Gatwick), ceased operations decades before, and their successor, British Airways, announced in 2016 that they would no longer accept unaccompanied minors.

To fly alone as a child was my first taste of what it might feel like to be on my own in the world. The orphaned or lost child is a trope of childrens literature: Cinderella, Anne of Green Gables, Tom Sawyer, Oliver Twist, Mowgli, Mary in The Secret Garden , Peter Pan, Harry Potter, Nemo. The young heroes and heroines are unleashed into the enormity of the world, and must prove their courage and resilience as they find home or simply a way to survive.

The unaccompanied minor was a legacy of Empire: the children of colonial officers sent from Kenya, Tanganyika, Ceylon, Hong Kong and India to be educated at boarding school in Britain. In the early days of Empire, the children would have travelled by ship and they probably would have visited their parents only once a year, if at all. Air travel changed that, allowing more frequent visits. BOAC became Britains national carrier and was created out of the merger of Imperial Airways and another national airline, the first British Airways. During the Second World War, BOAC was tasked with keeping Britain connected to her colonies and the airline continued to maintain those routes after independence.

I was a legacy of Empire as well. But for the Berlin Conference of 1885, which marked the end of the Scramble for Africa and at which the imperial ambitions of the European nations were formalised, my parents would never have met. Africa was stripped of her autonomy and decades of colonial rule followed. After the Second World War, Britain, penniless and under pressure from the United States, handed her colonies their independence with growing haste. Anthems were composed, flags designed, various royals dispatched to oversee the ceremonies at which the Union Jack was lowered. That was the easy part. One among many problems was that there was nobody to run these new states, all of which required lawyers, accountants, engineers, doctors. So, in the years preceding independence, young men and women from the colonised countries were granted scholarships to study in Britain. They were the Renaissance Generation, so named by the writer Wole Soyinka, a generation who came of age at the same time as their countries. One of them was my father. At a reception hosted by the British Council in Aberdeen he met a local girl who would become his wife and my mother. Through my parents, and later my mothers remarriage to a UN diplomat, I had an unusual exposure to large parts of the world. In my family are represented the histories and nations of Britain, Sierra Leone, Jamaica, Iran, Denmark, China, New Zealand and Canada.