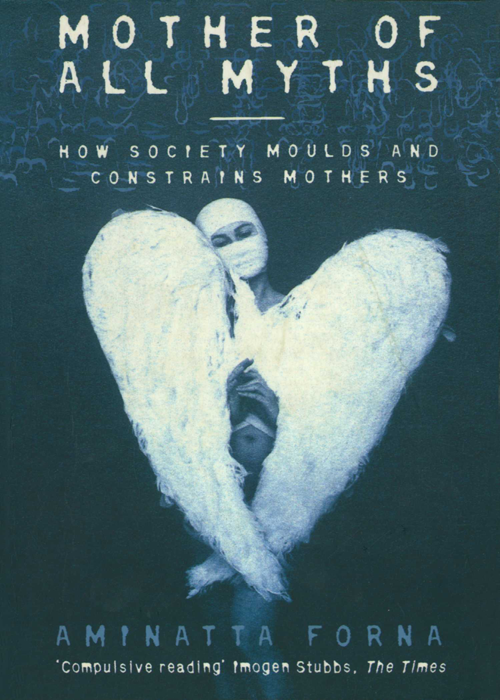

AMINATTA FORNA

MOTHER OF

ALL MYTHS

How Society Moulds

and Constrains Mothers

To Simon

chapter 1

Introduction: The Motherhood Myth

There have been a few key public moments during the research and writing of this book which serve as good illustrations of what it is all about. On a daytime chat show about teenage rebellion, a woman seeking desperately to explain the behaviour of her adoptive daughter apologized over and over again: I know Im not her real mother, but During the O. J. Simpson trial in 1995, prosecutor Marcia Clark fought simultaneous battles to win a conviction in the trial of the decade and to keep her children. Her ex-husband was trying to win custody on the grounds that she was working too hard to be a good mother. When the toddler Jamie Bulger was murdered, I recall reading that his mother had received hate-mail blaming her for looking away for an instant! After the second royal divorce, on what did the press blame the British royal familys misfortunes? Not their own constant intrusion but on the notion that the Queen was a cold and distant mother. Then there was the firestorm of criticism that greeted the announcement of Madonnas pregnancy. Comment on her unsuitability as a mother led to the dismissal of the childs father as a sperm donor, followed, naturally, by speculation after the birth that the state of motherhood would change the singer, a woman who is herself the mistress of image manipulation.

The most public humiliation any mother has ever been forced to undergo was reserved for Deborah Eappen. She was the mother of Matthew Eappen, the small child whose death was at the centre of the murder trial of British au-pair Louise Woodward. For many people, from the very beginning, she was the person who was on trial and not Woodward, because she chose to work three days a week as an ophthalmologist instead of being a full-time mother, because she was married to a doctor and did not need to work, because she left her children to be cared for by someone else. A woman grieving the loss of her child was being torn apart instead of comforted, derided instead of consoled. In the fervour of the lynch-mob mentality, little Matthew was all but forgotten as people carried placards in front of the court bearing the words Dont Blame the Nanny. Blame the Mother! They called television and radio phone-ins to scream how she deserved to lose her baby, and vented their hatred of her in a specially-created Internet website. People ignored the fact that Deborah Eappen came home to breastfeed at lunchtime and that she had halved her workload. People ignored the fact that Matthew had another parent who was also a doctor. It was left to Sunil Eappen to defend his wife, because she could not defend herself and because he, merely the father, was not seen to be at fault. The baby died because she wasnt there.

A great deal has been said and written about motherhood. The only purpose of the bulk of what has already been published is to tell women how to do the job better. You could fill the Augean stables with past volumes of advice to mothers. This book purports to do none of that. I hope it will be many things to many people, mothers and non-mothers, but it is absolutely not a childcare manual.

The rhetoric of motherhood has remained unchallenged for so long that it has become woven into the fabric of our consciousness. For once lets turn the searchlight on those who presume to tell mothers what to do; to analyse their actions, unpick their motives and judge their handiwork, just as they have done not only to mothers but to all women because they have the potential to be mothers. Once held up to the light, the agendas behind many of our assumptions and beliefs about contemporary mothering are exposed, whether their roots are in popular culture, so-called scientific findings, historically accepted fact or the legacy of tradition. First you find the flaws in what are presented as crystal-clear truths and then you see how the flaws form patterns. Finally, you begin to realize that myths have been created about motherhood and see how those myths refract through the many prisms of our culture and through time itself.

The motherhood myth is the myth of the Perfect Mother. She must be completely devoted not just to her children, but to her role. She must be the mother who understands her children, who is all-loving and, even more importantly, all-giving. She must be capable of enormous sacrifice. She must be fertile and possess maternal drives, unless she is unmarried and/or poor, in which case she will be vilified for precisely the same things. We believe that she alone is the best caretaker for her children and they require her continual and exclusive presence. She must embody all the qualities traditionally associated with femininity such as nurturing, intimacy and softness. Thats how we want her to be. Thats how we intend to make her.

The ideology which accompanies the myth of the perfect mother can only conceive of one way to mother, one style of exclusive, bonded, full-time mothering. Despite the changes in the working and family lives of millions of women, despite the talk of an age of post-feminism, attitudes towards mothers are stuck in the dark ages. Thirty years on from the start of the second wave of the feminist movement, we are still debating the effects of daycare on the children of working mothers and blaming never-married or divorced mothers for their childrens problems. This vision of idealized motherhood still permeates every aspect of life from the division of labour at home, to our employment laws, policies and legal rulings, and it drips down continually through popular culture, books, television, films and newspapers.

The ideal mother is also the natural mother, hence the stereotype of the wicked stepmother. The maternal ideal is based on a belief in what is natural, on notions of maternal instinct. Today there is a renewed reverence for ideas about maternal instinct, which has been prompted by the fear that motherhood, one of the two pillars upholding the institution of the family alongside marriage, is being threatened. It stands to reason, then, that if maternal qualities are natural, all women must have them. The growing number of women who choose to delay or avoid motherhood altogether fascinate and alarm the myth-makers because they defy the myth. For them, new mini-myths are invented to try to co-opt them into the maternal state.

Theres a moment in the popular film When Harry Met Sally in which the main character, played by Meg Ryan, is discussing man problems with her best friend. Youre thirty-one. The clock is ticking! warns her chum. No it isnt, she replies. I read it doesnt start until youre thirty-six. The notion of the so-called biological clock is a great example of contemporary mythmaking. The clock has two hands. On the one hand theres the fact that a womans fertility declines over time, which is true and which is being shamelessly exploited to make women anxious about the decision when to have a child. On the other hand, theres the notion, as expressed by the character Sally in the film, that the urge to have a child strikes all women at a particular time, without warning and independent of all intellectual thought processes, which is palpable rubbish and has no scientific basis whatsoever. Those women who say they have experienced a natural urge or need to have a child do so at different times of their lives and in different ways; plenty of women never do. Nevertheless, these two ideas are rolled into one and delivered as gospel in such a way as effectively to browbeat women (including those who may feel ambivalent about having children) into the institution of motherhood. Listen to your heart not your head, is the message.

Next page