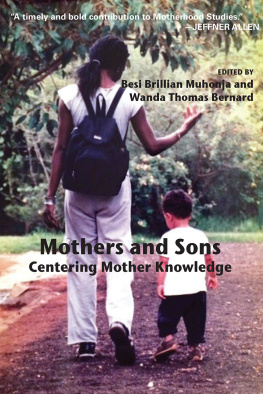

Mothers and Sons

Centering Mother Knowledge

Copyright 2016 Demeter Press

Individual copyright to their work is retained by the authors. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means without permission in writing from the publisher.

Funded by the Government of Canada

Financ par la gouvernement du Canada

Demeter Press

140 Holland Street West

P. O. Box 13022

Bradford, ON L3Z 2Y5

Tel: (905) 775-9089

Email:

Website: www.demeterpress.org

Demeter Press logo based on the sculpture Demeter by Maria-Luise Bodirsky < www.keramik-atelier.bodirsky.de >

Printed and Bound in Canada

eBook: tikaebooks.com

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Mothers and sons : centering mother knowledge / edited by Besi Brillian Muhonja and Wanda Thomas Bernard.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-77258-018-1 (paperback)

1. Mothers and sons. 2. Motherhood. 3. Parenting. I. Brillian Muhonja, Besi, 1972, author, editor II. Bernard, Wanda Thomas, author, editor

HQ755.85.M76 2016 306.8743 C2016-903613-8

Mothers and Sons

Centering Mother Knowledge

EDITED BY

Besi Brillian Muhonja and Wanda Thomas Bernard

DEMETER PRESS

Table of Contents

Acknowledgements

Our appreciation goes first to the brilliant contributing authors whose work we share in this volume and every bold mother whose narrative they share. We extend our gratitude to the Demeter Press team for their support in every way. We especially acknowledge Andrea OReilly for her vision beyond this anthology and her critical role in furthering Motherhood Studies as a discipline.

Besi: I thank my family and friends who inspire and support me, especially my mother, Hellen Muhonja Alumasa, a true feminist visionary; my sisters, Joy, Maureen, Cynthia and Melody, and our babies; my academic mother, Nkiru Nzegwu; and my brother and interlocutor, Cheikh Thiam. To Mama Ojok and Ojok, thank you for so much, and for the cover image. Wanda, thank you for exploring this work with me. A final thanks goes to my very talented research assistant, Rebecca Klein.

Wanda : I am grateful to my spouse of over forty years, who supports every project I take on. I wish to thank all of the men whom I have worked with over the years. Understanding your life journeys and your roles as sons, fathers, brothers, uncles, friends and colleagues has helped me to appreciate your uniqueness as men of African descent and my role as an insider-outsider. My daughter Candace reminds me every day of the significance of mothers, especially black motherhood. I am indebted to all of my sister friends who continue to inspire me to use words as acts of resistance and to my mother who left me a legacy of what it truly means to be a mother in good times and in bad times. Finally, I want to thank you Besi for inviting me to join you in this very interesting project.

Introduction

Mothering at Intersections: Towards Centering Mother Knowledge

BESI BRILLIAN MUHONJA

T HIS BOOK IS PRINCIPALLY ABOUT mother knowledge and not knowledge about mothers. Centring mother knowledge demands a focus on the conceptual, cognitive, and experiential processing of the mother and not that of the scholar. What mothers know subliminally and cognitively, and which they retrieve and apply actively or otherwise in different situations, speaks to a unique insight, which is learned, acquired and embodied. The application of this contextual and conditional knowledge influences and is influenced by practices, philosophies, traditions, and institutions that individual mothers are connected to. Mother knowledge, therefore, expands with compounding maternal experiences for each mother. Thus, one must speak of particular mother knowledge as well as collective mother knowledge imbued with sentience, know-hows, praxes, and affectivity.

Mother knowledge, even the conceptual, is mostly experiential knowledge; what seems conventional is fortified for mothers by interaction with and understanding of the connections between specific individual(s) and the mother cosmos. Different pairings of individuals and circumstances produce differently nuanced knowledges, which subsist in lifeworld(s) where the natural, spiritual, and social worlds interface. The mother and other(s) encounter this world in what Achola Pala refers to as different dimensions of motherhoodbiological, spiritual, and social (8). To perform in any of these scopes demands a negotiation of familial, cultural, societal, political, and economic realities and structures. This is where the completeness of mother knowledge resides because here, the particular intersecting identities and actualities of each mother come into play.

Particularizing knowledge to specific mothers or mother groups allows us to transition into making generalizations as scholars and scholarship define mother knowledge and create credible frameworks around it for studying mother-related phenomena. This is because, at once, the particularization of experiences and knowledges allows us to maintain individuals mother-wit and voices and, also, affords insight into how far the universalization of mother experiences can be functional or not. Expanded individuation allows for critical generalization, distinguishing the mother beyond the person and allowing her to become representative of collective knowledge and memory. In this collection of academics writing motherhood, in centring mother knowledge, the autoethnographic eye is ever present. This book, by embracing the analysis of the self and the personal, with scholars theorizing while maintaining the voices of the mothers and sons, privileges mother knowledge. Such a focus invites the authors to be subjects writing themselves, or to centre the mothers when the authors are not personally located in the work. This academic production, therefore, endorses the personal narrative and personal political spaces as a requisite for analytical studies on motherhood, and this introduction, accordingly, foregrounds the contributors mother knowledge by primarily citing the chapters within the volume. Analysis that erases mother voices expunges the different complexities of motherhood and, worse still, reinforces partiality towards patriarchally constructed motherhood. Therefore, commitment to centring phenomenological mother knowledge, and not just knowledge about mothers, informed the selection of the contributions in this collection. The result was the birth (pun intended) of a book that presents diverse ways of knowing, being, and experiencing motherhood and sonhood.

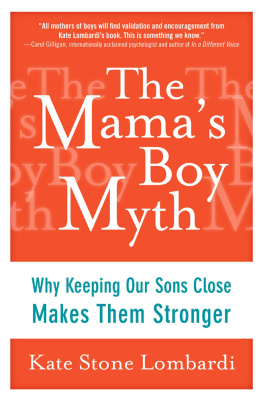

What this book responds to, therefore, is the dearth of scholarship on motherhood in relation to sonhood, which has been occasioned by the fact that conceptual and empirical research as well as creative works tend to primarily contemplate parental interactions and influence in same-sex generational dyads: mother-daughter or father-son. The philosophy held by many that fathers raise sons and mothers raise daughters has compromised investment in research in this area. Although in many heterosexual and co-parenting circumstances both parents contribute to the raising of children from all genders, and many lone and lesbian mothers raise sons without male partners, society in general, consciously or not, still affiliates sons to fathers and stigmatizes particular closeness of sons to mothers, which spawns the pejorative label mamas boy. Considerations of the mother-son relationship focus on subjects associated with the psychological effects of hyper-involved parenting by mothers of sons, attributing therein good and bad mothering of sons. These contemplations presume a uniform approach to the proper parenting of sons. Such a lens assumes gendered parental legacy and focalizes patriarchal estimations of motherhood.