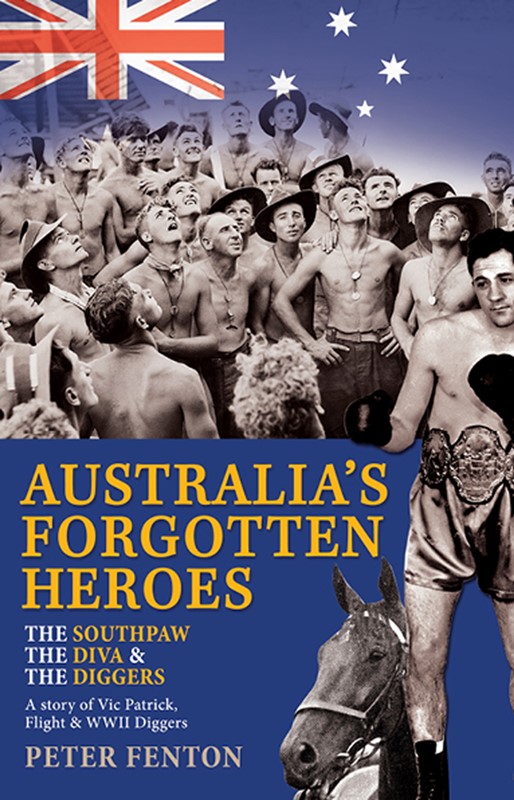

THE SOUTHPAW,

THE DIVA &

THE DIGGERS

A story of forgotten Australian heroes

Vic Patrick, Flight and World War II Diggers

| Published by Brolga Publishing Pty Ltd ABN 46 063 962 443 PO Box 12544 ABeckett St Melbourne, VIC, 8006 Australia |

email:

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without prior permission from the publisher.

Copyright 2015 Peter Fenton

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication entry

Fenton, Peter, author

The Southpaw, the Diva & the Diggers

ISBN: 9781925367102 (paperback)

ISBN: 9781925367539 (ebook)

Subjects: Boxers --Horse racing-

Australia--History--1939-1945

796.0994

Printed in Australia

Cover design by Wanissa Somsuphangsri

Typesetting by Tara Wyllie

THE SOUTHPAW,

THE DIVA &

THE DIGGERS

A story of forgotten Australian heroes

Vic Patrick, Flight and World War II Diggers

PETER FENTON

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

English author Alan Ross was referring to cricket when he wrote, Heroes in fact die with ones youth. They are pinned like butterflies to the setting board of early memories the time when skies were always blue, the sun shone and the air was filled with the sounds and scent of grass being cut. This is not only beautifully put but is highly perceptive. Sporting heroes are never as important as when you are young. Then, mere mortals assume a dimension in impressionable minds that defies logic and relies more on magic.

And yet there can be contributing factors apart from youth that might elevate sports heroes to another level. The great depression that gripped the country in the early 1930s was one. In a nation where so many were imbued with an innate love of sport it was only natural that, while suffering its hardships, people found inspiration in their sporting heroes. Suddenly they resumed the importance of the idols of their youth.

The mighty racehorse Phar Lap, despite his undeniable greatness, could not really have become the legend he did without the circumstances during which he raced. The nation sought a hero and found one. An apparently cumbersome colt, purchased for a song by a door-to-door salesman and prepared by a trainer struggling to pay his bills, went on to defeat the highest priced colts owned by people with means far above the norm. Each time he left his superbly-pedigreed, high profile rivals floundering, his victory was celebrated even when his price was too short to allow his fans to back him. He was the battler who had defied the hardships in a way similar to that which they were asked to do on a daily basis. He had beaten the odds.

And of course there was Bradman. The country boy who played cricket with his father and uncles and honed his hand eye coordination by hitting a golf ball against a round galvanised iron tank with a cricket stump as others hit tennis balls against a wall. The county boy who came to town and tamed the best bowlers in the city, and later in England, in the greatest sporting contest that Australians played; the battle for the Ashes. He too was a hero of the depression.

As the country struggled to overcome the depression years they were met with an even greater disaster. During the Second World War, Australia, for the very first time, faced the possibility, most believed the probability, of invasion. A war that seemed a long way off was suddenly on our doorstep with Japans devastating attack on Pearl Harbor, the invasion of Singapore and the bombing of Darwin. Young men joined up in their thousands. Newspapers which had been filled with stories of Australian servicemen facing death in places previously unknown to them now reported similar danger nearby in the Pacific. At home, every action revolved around the war. Rationing of essential items like food, clothing, tobacco, beer and petrol made times extremely tough, way beyond the understanding of later generations.

As the Olympic Games and international contests in cricket, football and tennis were abandoned, sporting heroes again assumed the role of saviours of sanity. The diversion from worry and pressure offered by an afternoon of sporting excitement was a Godsend. Servicemen returning on leave to play club cricket and football all across the country gave pleasure to those whose loved ones were absent in the Middle East, the Pacific Islands or military camps all over Australia.

The popularity of horse racing and boxing during this time is difficult to comprehend today. Racing and boxing crowds were similar, if not identical. Now, both sports have largely lost their mass appeal except for special carnivals and world title fights. A city like Sydney now has one radio station broadcasting a never ending mix of often inconsequential galloping, harness racing and greyhound racing. It exists because it belongs to the sport.

During the war and the years immediately following, no fewer than three commercial stations, as well as the ABC, broadcast each race from Sydney and Melbourne every Saturday. Soon after the war the ABC was also broadcasting the fights from Sydney Stadium each Monday night, along with at least two and often three commercial stations. There was no television. Radio was king.

Despite various restrictions placed on both sports these would come to be regarded as halcyon days, producing several great champions and many memorable battles. Seventy to eighty thousand patrons attended the feature race carnivals at Randwick as well as Flemington. Crowds of forty and fifty thousand were commonplace. These crowds were bolstered by a large contingent of uniformed servicemen who were admitted free of charge. Among a host of equine champions, a nuggety, bay mare won the hearts of race goers with her courage and brilliance. Flight, who was the cheapest lot sold at the 1942 Easter yearling sales, took her place in racing history alongside two outstanding stallions, Bernborough and Shannon. In Melbourne another queen of the turf, Tranquil Star, was to Victorians what Flight was to Sydneysiders. Their clashes, at wars end, were to determine the greatest stake winning mare ever to race in Australia.

In the capital cities, particularly on the East coast, boxing fans queued each Saturday night for tickets to see local and overseas boxers. In Sydney the largest and most famous stadium was at Rushcutters Bay, but during the week Leichhardt Stadium was also regularly packed for a night of boxing. Smaller venues were located in outer suburbs. When the pubs closed at 6 oclock crowds flocked to the stadium. The standard was high with any number of youngsters anxious to earn an extra quid in the one sport that offered such an opportunity.

As a young, crowd-pleasing southpaw named Vic Patrick, blessed with a left hand like the kick of a mule, built up an imposing record the queues got longer and longer. It was ironic that Patrick was actually Italian. While his countrymen were being interned all over Australia, Vic was accepted by the patriotic and parochial fight crowd as one of their own. The tenth child of a very poor, illiterate Calabrian born fisherman and a mother of Spanish descent, Patrick rose from abject poverty to become the greatest draw card that Sydney Stadium, the famous Old Barn, had seen since the time of World War I and the immortal Les Darcy. His popularity was immense.