How has the idea of the South come to exert such a powerful hold over our imagination? From the beaches of Southern Europe to the Great White South of the Antarctic; from South America to the South Pacific, South explores this most diverse and captivating of regions.

The South has long since cast its spell on writers and artists, from Goethe and Poe, to Gauguin, Lawrence and Kerouac; while landscapes of ice and snow, sand and sea, have lured explorers southwards for centuries, often with fatal consequences. This book will follow in the footsteps of Cook, Scott, John Muir and others as they recount their journeys.

About the author

Merlin Coverley is the author of five books: London Writing (2005); Psychogeography (2006); Occult London (2008); Utopia (2010) and The Art of Wandering: The Writer as Walker (2012). He lives in London.

I shall go further south feel I want to go further and further south dont know why.

DH Lawrence

Contents

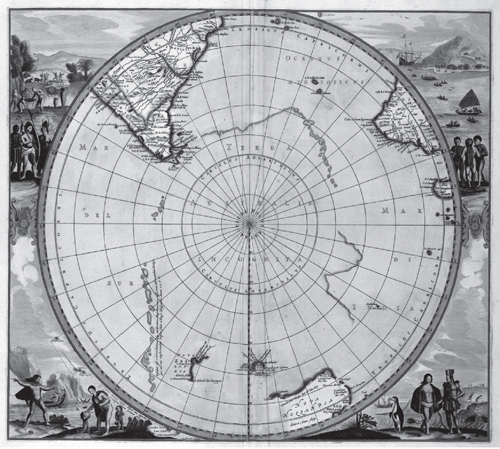

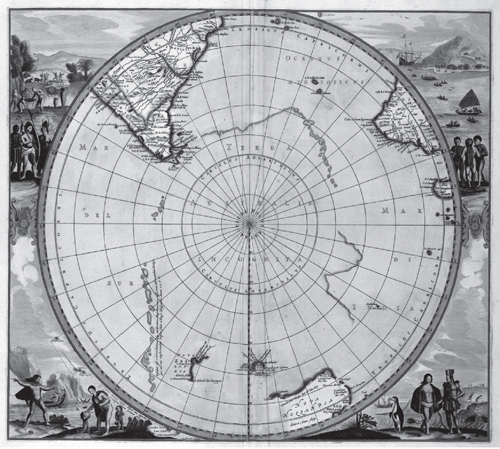

Map of the South Pole by unknown artist (17th Century)

Every person is born with his own north or south, whether he is born into an external one as well is of little consequence.

Jean Paul

Our sense that north is up and south is down is purely an artefact of map-making conventions in the northern hemisphere.

Gyrus

In 1989 the landscape artist, Andy Goldsworthy, constructed four circular arches from snow bricks, positioning them to face one another across the arctic axis at the North Pole. Goldsworthy named his sculpture Touching North, an ambiguous title for a work which demonstrates how the directions of the compass may effectively be rendered meaningless: emerge through any of the four arches and one finds oneself heading south. Such a definition suggests an equality between such designations, the one informed by the other, and vice versa. Yet within the family of cardinal points, some directions are clearly more equal than others. For Touching North is also indicative of the unstated but nevertheless unequal relationship which governs our understanding of north and south, the one implicit within the other yet somehow ancillary to it.

The fact that most early civilisations are now believed to have developed to the north of the equator goes some way to explaining the privileged position the north has since acquired as the summit of the world. The enduring power of such a worldview is demonstrated by the fact that even civilisations such as that of the Mayans in the southern hemisphere regarded the North Pole as the top of the world, despite the fact that at their latitude it is barely fifteen degrees above the horizon. While at an even more southerly latitude of some 13.5 degrees south of the equator, the indigenous population of the Incan capital of Cuzco in Peru also regarded the upper part of their city as that which lay to the north, despite the North Pole lying well below the horizon, a fact which has since been attributed to the influence of the southward migration of Stone Age colonists. Historical representations of the south, as well as the mythology in which they are embedded, will be explored elsewhere in this book. But in seeking the origin of the dominant position which the north has come to hold over its southern counterpart, it is useful to note the comments of the author, John T Irwin, who has outlined the evolution of this disparity:

Just as there is a privileged pole in each of the oppositions associated with bodily directionality (i.e., front over rear, right over left), so there is also a privileged pole in each of the oppositions associated with geographic directionality. [] In the definitions of right and left and of east and west , it is stipulated that one be facing north; while in the definitions of north and south the condition is that one be facing the sunset (west). This preference for north over south and west over east as the directions one faces in order to define the other cardinal points and the sides of the body can perhaps be explained in terms of practical navigation. The privileging of the north probably results in part from the fact that on a day-to-day basis the North Star is a more reliable approximate indicator of true north than the rising sun is of true east or the setting sun of true west, while the privileging of the west may well be a function of the fact that in the modern world the suns setting is an event likely to be observed by more people on a given day than the suns rising. Yet in the privileging of one pole of a differential opposition over another, there is always a cultural bias at work, and certainly the favored status of north and west in these definitions results in part from their being the directions most closely associated with both the geographic location and the historical designation of that culture represented by the dictionary, the modern, scientific culture of that industrialized portion of the northern hemisphere traditionally referred to as the West.

As Irwins comments suggest, both west and north, whether as a consequence of astronomical considerations or through cultural bias, have come to be seen as the privileged cardinal points, as well as the global designators of wealth and political power. As for the Orient (from the Latin oriens ), this has long since been equated with the spiritual radiance of the rising sun, with the churches of the Christian faith orientated to the east; this is widely held to be the pre-eminent sacred direction, the point by which to orient oneself, to place oneself in this world with regard to the divine.If then, these three points of the compass can so readily be assigned a role, albeit a symbolic one, what of the remaining cardinal point, the south? In what manner should this direction, this region of the globe, be portrayed? This book will attempt to provide an answer to this question, by exploring some of the worlds souths and the many different ways in which they are represented.

One such way, of course, is via the convenient but monolithic shorthand of the Global South, the collective name for the industrially and economically less advanced countries of the world, typically situated to the south of the industrialised nations. Yet if this is a region which has, however unfairly, become perceived as one synonymous with poverty and deprivation, it is also one which has often been depicted historically, from a Western perspective at least, as an empty region, a blank slate which has been repeatedly overwritten by the mapmakers and mythologists of the northern hemisphere.

There are many ways in which the cardinal points may be brought to life, and many symbols which may be attributed to them, from colours to mythological creatures; from times of the day to seasons of the year; from winds and weather to gender and bodily form. In Cesare Ripas iconographical compendium, Iconologia (1593), for example, they are personified in the following manner: the east is a pretty youth, with golden locks; holding flowers in his right hand ready to blossom, he represents the morning and the rising sun. The west, by contrast, is an old man holding a bunch of poppies in his left hand; his is the representation of the setting sun at the close of day. The north is depicted by a man in the prime of life, fair-haired, blue-eyed and of a ruddy complexion; suited in white armour, his hand clasping his sword, his habit of body denotes the quality of the cold climate that makes men have a good stomach, and quick digestion; his posture, as he stands tall against a backdrop of cloud and snow, reflects the bravery of the northern people. While in the south we see a young black man illuminated by the noon-day sun above his head; in his right hand, arrows, representing the suns penetrating rays, in his left, a lotus branch, symbolising water . One does not require a keen understanding of Ripas complex symbolic vocabulary to identify the dominant figure here.

Next page