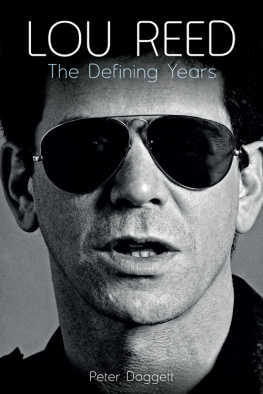

Copyright 1992 Omnibus Press

This edition 2012 Omnibus Press

(A Division of Music Sales Limited, 14-15 Berners Street, London W1T 3LJ)

Picture research by Glen Marks and Dave Brolan.

EISBN: 978-1-78323-084-6

This book was originally published as Growing Up In Public.

The Author hereby asserts his / her right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with Sections 77 to 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages.

Every effort has been made to trace the copyright holders of the photographs in this book, but one or two were unreachable. We would be grateful if the photographers concerned would contact us.

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library.

For all your musical needs including instruments, sheet music and accessories, visit www.musicroom.com

For on-demand sheet music straight to your home printer, visit www.sheetmusicdirect.com

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ID FALLEN FOR THE RAVE REVIEWS THAT greeted Mistrial in 1986, and been gravely disappointed. When the publicity campaign for New York in January 1989 bragged that Lou thought this was his best ever record, I remembered the words of Mandy Rice-Davies: Well, he would say that, wouldnt he? It was a new label, a new deal, a new record to be sold. After three years of silence, and the three before that of creative anonymity, another Lou Reed record was neither here nor there.

That was until I heard it. Like everyone else, I was impressed by the artistic ambition of New York, its lyrical verve, its humour and imagery. Where did it come from? How could the man who thought Mistrial an appropriate response to the 1980s have channelled so much experience into one record.

The seeds of this book were planted then. New York sent me back to the rest of Reeds back catalogue, not just to the accepted glories of The Velvet Underground and the glam-rock era, but also to the dark and challenging work of the late seventies and early eighties. Faced by the critical commonplace that Reed was a genius of the sixties and a sorry wastrel thereafter, I was pulled by the need to set the record straight, to shout from the rooftops that his career was - as Lou had always claimed - one long autobiographical novel, an uncompromising record of personal loss and growth.

Although Reeds time with The Velvet Underground has been documented in print, no-one has ever attempted to survey his entire career with the same degree of sympathy. Contrary to popular belief, Reed and the Velvets were not the lucky recipients of some freakish spark of the imagination, which then lay dormant until it was miraculously rekindled on New York. Reeds work is actually one seamless tapestry of exploration and nerve, which has its antecedents in the New York art scene of the sixties and the proud literary history of his homeland. Thats off-limits for most rock criticism, which tends to see music as enjoying a direct line to the streets, but baulks at any notion that it might fit into wider artistic movements. Lou Reed has never made any secret of the fact that it is literature, as much as rocknroll, which has been his choice of weapon.

Facts are easy enough to assemble but what really matters is perspective. I was lucky enough at an early stage of this project to be put in touch with Glen Marks, who had both at his fingertips. As a keen follower of Reeds career since the early Seventies, Glen has marshalled an impressive collection of information, memorabilia, gossip and researched knowledge - probably unequalled in the world - without which this book would have been much less substantial.

More importantly, Glen was an endless fund of theories, ideas and speculation. Sometimes these notions coincided with mine, sometimes not, but the stimulus was a lifeline at times when it seemed that Reeds career was too bizarre to assimilate. For a man who has long harboured a wish to write his own account of Reeds life and work, Glen took my invasion of his territory with exceptional grace. Its a clich to say the book could not have been written without him but for once the clich is true.

Elsewhere Louise Cripps acted as a one-woman support team while I was writing this book, for which I am once again extremely grateful. I still dont think she likes Metal Machine Music though. Mark Paytress does, and his enthusiasm for the avant-garde has resulted in some heated discussions over the last five years, most of which I have won only because I was wielding the editorial red pen. He read parts of the work in progress, and provided an informed view of the music and art that time (and the mainstream) forgot.

Chris Charlesworth not only edited the manuscript but back in 1977 bought two of Lou Reeds many black and white televisions, neither of which worked particularly well. He was able to bring his recollections of the people and places involved in the New York Seventies scene to this book. Johnny Rogan has proved to be an enthusiastic and expensive telephone correspondent over the last five years, and although a mere novice in the ranks of Lou Reed alumni, his refusal to let lazy thinking pass without contempt has been a long-distance source of inspiration every time I dare pick up a pen. Debbie Pead read much of the manuscript, and many of the ideas thrown around inside this book were first aired during our conversations sometime over the last 15 years.

Brian Hogg proved, as ever, to be the person who has exactly the information I wanted on the day I wanted it, and also inspired me to listen to Archie Shepp and Ornette Coleman. John Platt and Eva Hunte offered useful ideas on Andy Warhol, while some of Clinton Heylins theories about Lou Reed were provoking, and others provoking but unprintable. Mention should also be made of Nicki Pritchard and Linda La Ban for friendship and support; and the staff of the University of London Library, the Hayward Gallery, the New York Museum of Modern Art, the Library of Congress in Washington and, of course, Record Collector. Finally, I am indebted to Andrew Dean, the first person to play me The Velvet Underground. Neither of us knew then what was in store.

Peter Doggett

INTRODUCTION

Ive had more of a chance to make an asshole out of myself than most people, and I realise that. But then not everybody gets a chance to live out their nightmares for the vicarious pleasures of the public.

(Lou Reed, 1979)

IN 1980, LOU REED MARRIED FOR THE second time. Four months later he released an album entitled Growing Up In Public, an uncomfortable merging of lyrical self-analysis and ersatz black music stylings. The record did not herald one of Reeds sporadic periods of acceptance by a mass audience; as a media event, it passed almost unnoticed. For Reed, however, it was a talisman of hope: a deliberate farewell to a decade in which he had paraded his private ghouls in the public arena. Reeds virtual disintegration during the Seventies began as a controlled chemical experiment, in which he tested the limits of his psyche and physique; eventually the sorcerers apprentice could no longer hold down the forces which he had conjured up, and Reeds life became a desperate effort to muster substance out of strife.