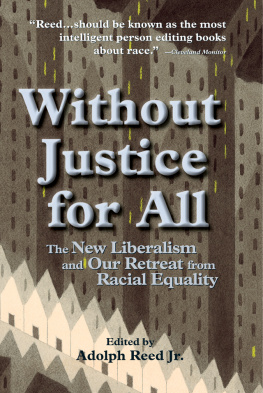

Adolph Reed Jr. - Articles of Adolph Reed Jr.

Here you can read online Adolph Reed Jr. - Articles of Adolph Reed Jr. full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 0, genre: Science / Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Articles of Adolph Reed Jr.

- Author:

- Genre:

- Year:0

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Articles of Adolph Reed Jr.: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Articles of Adolph Reed Jr." wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Articles of Adolph Reed Jr. — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Articles of Adolph Reed Jr." online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Over forty years ago Benjamin pointed out that mass reproduction is aided especially by the reproduction of masses.1 This statement captures the central cultural dynamic of a late capitalism. The triumph of the commodity form over every sphere of social existence has been made possible by a profound homogenization of work, play, aspirations and self-definition among subject populations a condition Marcuse has characterized as one-dimensionality.2 Ironically, while U.S. radicals in the late 1960s fantasized about a new man in the abstract, capital was in the process of concretely putting the finishing touches on its new individual. Beneath the current black-female-student-chicano-homosexual-old-young-handicapped, etc., etc., ad nauseum, struggles lies a simple truth: there is no coherent opposition to the present administrative apparatus.

Certainly, repression contributed significantly to the extermination of opposition and there is a long record of systematic corporate and state terror, from the Palmer Raids to the FBI campaign against the Black Panthers. Likewise, cooptation of individuals and programs has blunted opposition to bourgeois hegemony throughout this century, and cooptative mechanisms have become inextricable parts of strategies of containment. However, repression and cooptation can never fully explain the failure of opposition, and an exclusive focus on such external factors diverts attention from possible sources of failure within the opposition, thus paving the way for the reproduction of the pattern of failure. The opposition must investigate its own complicity.

During the 1960s theoretical reflexiveness was difficult because of the intensity of activism. When sharply drawn political issues demanded unambiguous responses, reflection on unintended consequences seemed treasonous. A decade later, coming to terms with what happened during that period is blocked by nostalgic glorification of fallen heroes and by a surrender which Gross describes as the ironic frame-of-mind.3 Irony and nostalgia are two sides of the coin of resignation, the product of a cynical inwardness that makes retrospective critique seem tiresome or uncomfortable.4

At any rate, things have not moved in an emancipatory direction despite all claims that the protest of the 1960s has extended equalitarian democracy. In general, opportunities to determine ones destiny are no greater now than before and, more importantly, the critique of life-as-it-is disappeared as a practical activity; i.e., an ethical and political commitment to emancipation seems no longer legitimate, reasonable or valid. The amnestic principle, which imprisons the social past, also subverts any hope, which ends up seeking refuge in the predominant forms of alienation.

This is also true in the black community. Black opposition has dissolved into celebration and wish fulfillment. Todays political criticism within the black community both Marxist-Leninist and nationalist lacks a base and is unlikely to attract substantial constituencies. This complete collapse of political opposition among blacks, however, is anomalous. From the 1956 Montgomery bus boycott to the 1972 African Liberation Day demonstration, there was almost constant political motion among blacks. Since the early 1970s there has been a thorough pacification; or these antagonisms have been so depoliticized that they can surface only in alienated forms. Moreover, few attempts have been made to explain the atrophy of opposition within the black community.5 Theoretical reflexiveness is as rare behind Dubois veil as on the other side!

This critical failing is especially regrettable because black radical protests and the systems adjustments to them have served as catalysts in universalizing one-dimensionality and in moving into a new era of monopoly capitalism. In this new era, which Piccone has called the age of artificial negativity, traditional forms of opposition have been made obsolete by a new pattern of social management.6 Now, the social order legitimates itself by integrating potentially antagonistic forces into a logic of centralized administration. Once integrated, these forces regulate domination and prevent disruptive excess. Furthermore, when these internal regulatory mechanisms do not exist, the system must create them. To the extent that the black community has been pivotal in this new mode of administered domination, reconstruction of the trajectory of the 1960s black activism can throw light on the current situation and the paradoxes it generates.

A common interpretation of the demise of black militance suggests that the waning of radical political activity is a result of the satisfaction of black aspirations. This satisfaction allegedly consists in: (1) extension of the social welfare apparatus; (2) elimination of legally sanctioned racial barriers to social mobility, which in turn has allowed for (3) expansion of possibilities open to blacks within the existing social system; all of which have precipated (4) a redefinition of appropriate black political strategy in line with these achievements.7 This new strategy is grounded in a pluralist orientation that construes political issues solely in terms of competition for the redistribution of goods and services within the bounds of fixed system priorities. These four items constitute the gains of the 1960s.8 Intrinsic to this interpretation is the thesis that black political activity during the 1960s became radical because blacks had been excluded from society and politics and were therefore unable to effectively to solve group problems through the normal political process. Extraordinary actions were thus required to pave the way for regular participation.

This interpretation is not entirely untenable. With passage of the 1964 and 1965 legislation the program of the Civil Rights movement appeared to have been fulfilled. Soon, however, it became clear that the ideals of freedom and dignity had not been realized, and within a year, those ideals reasserted themselves in the demand for black power. A social program was elaborated, but again its underpinning ideals were not realized. The dilemma lay in translating abstract deals into concrete political goals, and it is here also that the gains of the sixties interpretation founders. It collapses ideals and appropriateness of the programs in question.

To be sure, racial segregation has been eliminated in the South, thus removing a tremendous oppression from black life. Yet, the dismantlement of the system of racial segregation only removed a fetter blocking the possibility of emancipation. In this context, computation of the gains of the sixties can begin only at the point where that extraordinary subjugation was eliminated. What, then, are those gains which followed the passage of civil rights legislation and how have they affected black life?

In 1967 black unemployment was over seven percent; for the first five months of 1978, it averaged over twelve percent.9 Between 1969 and 1974 the proportion of the black population classified as low income has remained virtually the same.10 Black median income did not improve significantly in relation to white family income in the decade after passage of civil rights legislation,11 and between 1970 and 1974 black purchasing power actually declined.12 Moreover, blacks are still far more likely to live in inadequate housing than whites, and black male life expectancy has declined, both absolutely and relative to whites, since 1959-61.13

Thus, the material conditions of the black population as a whole have not improved appreciably. Therefore, if the disappearance of black opposition is linked directly with the satisfaction of aspirations, the criteria of fulfillment cannot be drawn from the general level of material existence in the black community. The same can be said for categories such as access to political decision-making. Although the number of blacks elected or appointed to public office has risen by leaps and bounds since the middle 1960s, that increase has not demonstrably improved life in the black community.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Articles of Adolph Reed Jr.»

Look at similar books to Articles of Adolph Reed Jr.. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Articles of Adolph Reed Jr. and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.