Contents

THE SOUTH

The Jacobin series features short interrogations of politics, economics, and culture from a socialist perspective, as an avenue to radical political practice. The books offer critical analysis and engagement with the history and ideas of the Left in an accessible format.

The series is a collaboration between Verso Books and Jacobin magazine, which is published quarterly in print and online at jacobinmag.com.

Other titles in this series available from Verso Books:

Class War by Megan Erickson

Building the Commune by George Ciccariello-Maher

Peoples Republic of Walmart by Leigh Phillips and Michal Rozworski

Red State Revolt by Eric Blanc

Capital City by Samuel Stein

Without Apology by Jenny Brown

All-American Nativism by Daniel Denvir

A Planet to Win by Kate Aronoff, Alyssa Battistoni, Daniel Aldana Cohen, and Thea Riofrancos

Toward Freedom by Tour F. Reed

Yesterdays Man by Branko Marcetic

THE SOUTH

Jim Crow and Its Afterlives

Adolph L. Reed Jr.

With a Foreword by

Barbara J. Fields

To

Kenneth W. Warren and Alex W. Willingham,

who inspired this project

And

Barbara Jeanne Fields and Faith Childs,

who made sure it came to fruition

First published by Verso 2022

Adolph L. Reed Jr. 2022

Foreword Barbara J. Fields 2022

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-83976-626-8

ISBN-13: 978-1-83976-629-9 (US EBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-83976-628-2 (UK EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

Typeset in Garamond Pro by MJ&N Gavan, Truro, Cornwall

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY

Contents

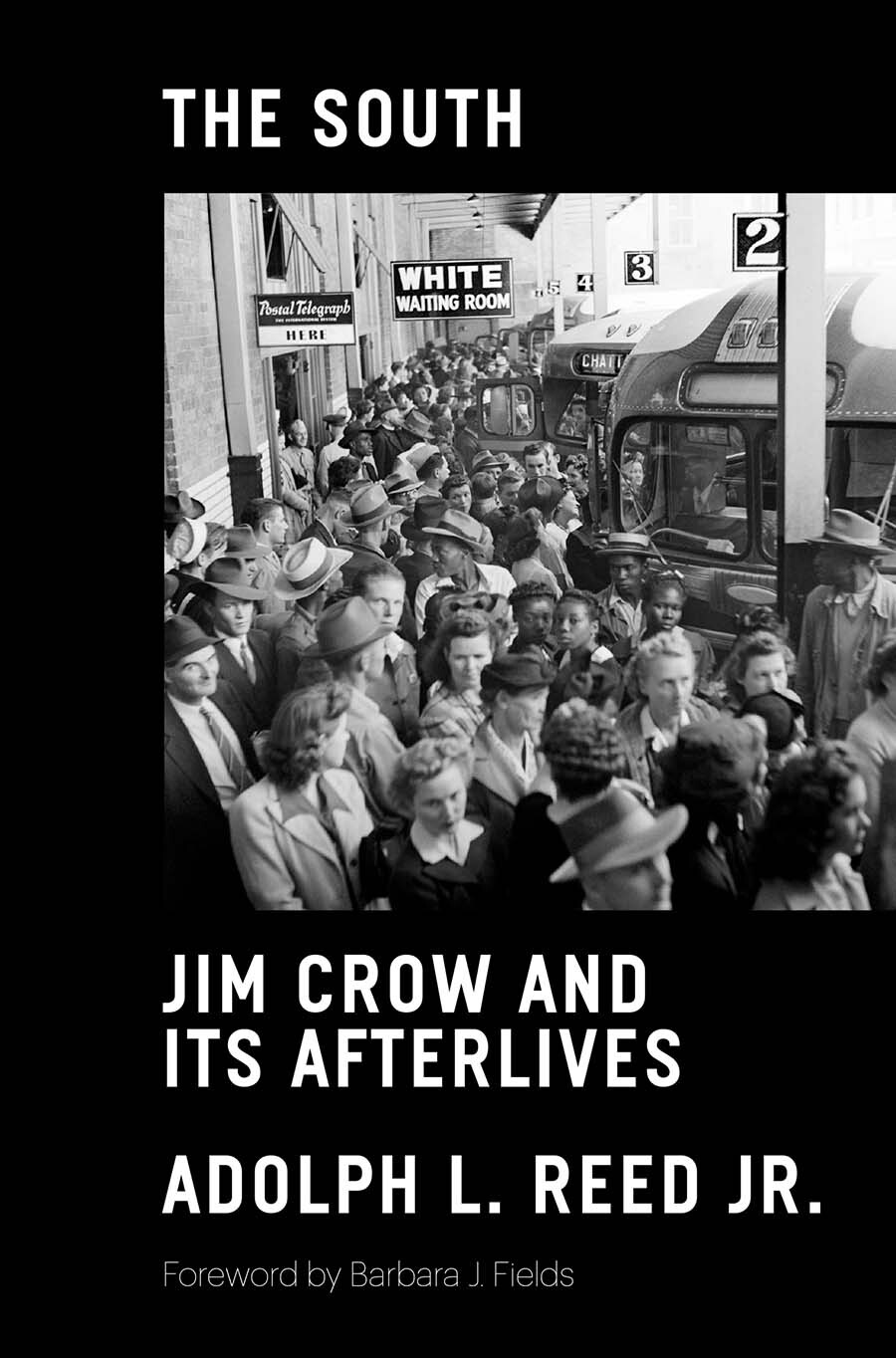

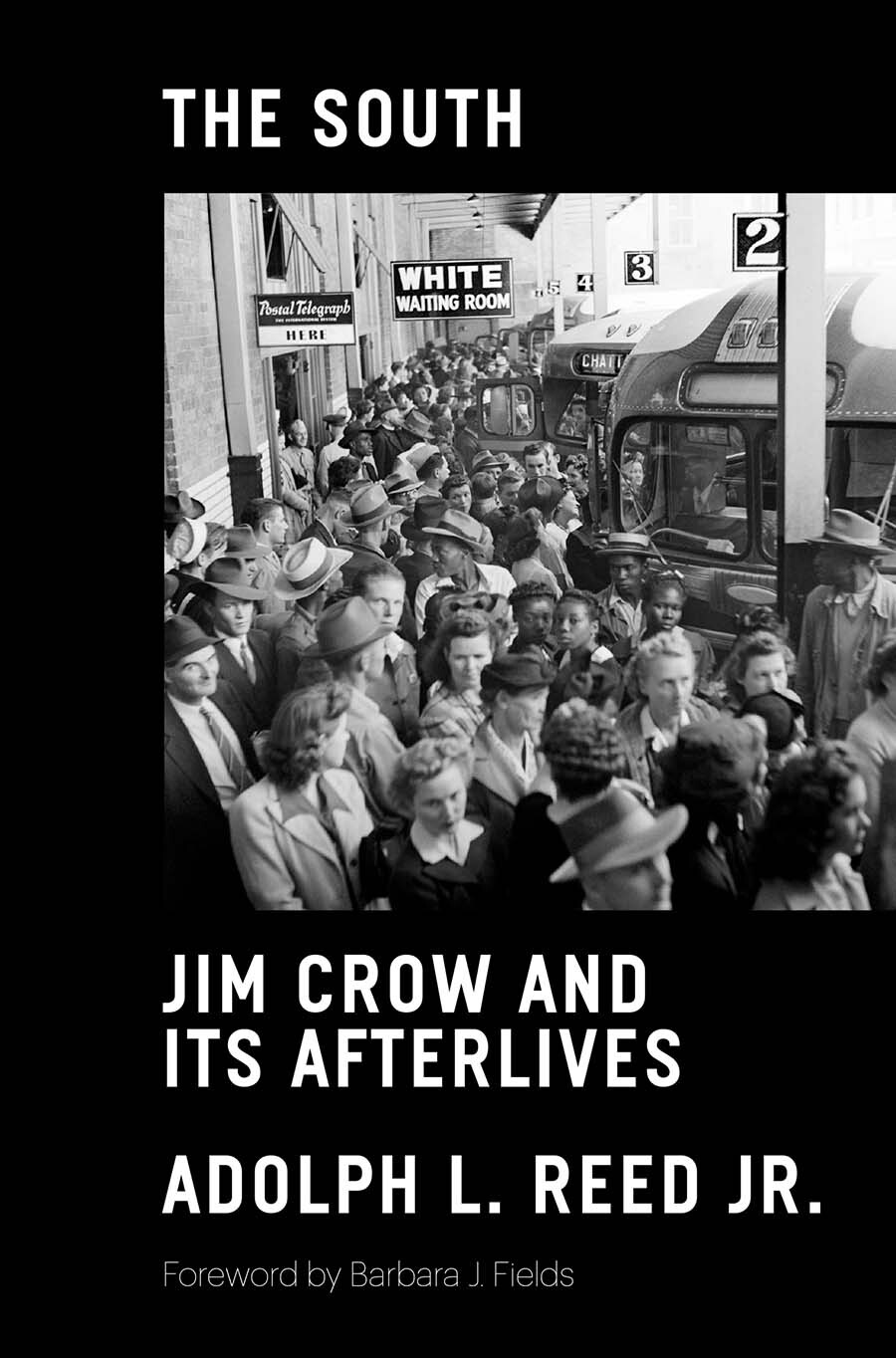

At a small deserted airport in El Dorado, Arkansas, during the spring of 1966, Adolph L. Reed Jr. faced a potentially life-and-death choice. Obliged unexpectedly to wait nearly three hours for a connecting flight, he approached the terminal to find two waiting room entrances, one at each end of the building. He had grown up in the Jim Crow South, so he knew what that meant. But since segregation in public accommodations had been against the law for two years, there were no signs to indicate which waiting room was which. Nor, on a Sunday afternoon (Palm Sunday or Easter Sunday, he recalls), was there a gathering of people in either one to provide a clue. Bearing vividly in mind recent high-profile murders of Northern white civil rights workers and frequent, anonymous assassinations of local black ones, Reed chose to avoid a potentially deadly mistake by waiting outdoors for his connecting flight (see pp. ). Among the lessons of The South is that tyrannical regimes can be at their most unpredictable and treacherous in the midst of dissolution.

Reed lays out the political stakes of his account early in the introduction. Despite popular historys fixing on slavery as the essentially formative black American experience, Reed insists that it is Jim Crowthe regime of codified, rigorously and unambiguously enforced racism and white supremacythat has had the most immediate consequences for contemporary life and the connections between race and politics. He makes good that insistence by knitting his recollections as a participant witness during the declining years of the Jim Crow system into an acute analysis of American politics from the mid-twentieth century to the early twenty-first.

Participants are not always the best chroniclers, let alone the best analysts, of transformations as profound as the dissolution of the Jim Crow system in the South. For persons taking daily part in such a system, the routine can so overshadow significant but subtle details that deviations from the baseline barely register as blips when they occur. After the fact, they may disappear altogether into the Nothing has changed or Plus a change plus cest la mme chose aphorisms that journalists, activists, and the lay public so readily invoke when discussing postcivil rights America. Public memory of Jim Crow tends, as a result, to become a stencil. Toggling between a blurb and a melodrama, the stencil seldom affords either a rounded picture of everyday peoples everyday lives or an adequate analysis of whose interests the system served, how it disintegrated, and what replaced it. The difficulty stems, in part, from what E. P. Thompson called the condescension of posterity. But the main problem is that many of those looking backwhether scholars, journalists, memoirists, or current activistslack the analytical or imaginative where-withal to reconcile Jim Crow as a daily lived experience with the standpoint of observers and analysts today, for whom life under Jim Crow lies beyond the threshold of memory.

Jim Crow was a series of locally varying accents within which the basic language was clear. Ef it wuznt fer them polices n them ol lynch-mobs, a friend of Richard Wrights remarked sardonically, there wouldnt be nothin but uproar down here! Nothin but uproar may have been intentional hyperbole since, even under a barbaric regime such as Jim Crow, people cannot live constantly at fever pitch. More likely, Wrights friend thought uproar an apt characterization of an everyday routine that, even when uneventful, unfolded amid tyrannical restrictions and an ever-looming threat of capricious violence.

With the eyes, ears, and keen political antennae of the outside insider, Reed picks out the quotidian routine within the uproar, bringing the quotidian to light without minimizing or losing sight of the uproar. The result is an uncommon tour of the Jim Crow world of his childhood and young adulthood, revealing, as he moves from place to place, a diversity of rules, textures, and colors that contradict the stencil version. For one thing, the rigid residential segregation of Southern cities that grew up after the Civil War did not prevail in Old South cities such as New Orleans. Reed offers a fascinating account of the ways black and white neighbors in New Orleans did and did not deal with each other, with some acknowledgments of each other permissible within the neighborhood but forbidden outside it. News that eggplants, satsumas, Creole tomatoes, crawfish, or mirlitons had appeared in markets, announcing their seasons arrival, was much too vital information to be blocked by the color line, he reports, for example ( ).

By design, the Jim Crow system overrode class distinctions among Afro-Americans, subjecting all, at least notionally, to the leveling discipline of white supremacy. Even so, middle-class black professionals and businesspeople, Reed reports, were better able than others to shield themselves from both the everyday indignities and the atrocities of the Jim Crow world ( ), taking them into account refutes any assumption that the black-white binary and accompanying class dynamics could have persisted unchanged from the Jim Crow era into the postcivil rights movement era.