Raising Racists

NEW DIRECTIONS IN SOUTHERN HISTORY

SERIES EDITORS

Peter S. Carmichael, Gettysburg College

Michele Gillespie, Wake Forest University

William A. Link, University of Florida

The Lost State of Franklin: Americas First Secession

Kevin T. Barksdale

Bluecoats and Tar Heels: Soldiers and Civilians in Reconstruction North Carolina

Mark L. Bradley

Becoming Bourgeois: Merchant Culture in the South, 18201865

Frank J. Byrne

Cowboy Conservatism: Texas and the Rise of the Modern Right

Sean P. Cunningham

Lum and Abner: Rural America and the Golden Age of Radio

Randal L. Hall

Entangled by White Supremacy: Reform in World War Iera South Carolina

Janet G. Hudson

The View from the Ground: Experiences of Civil War Soldiers

edited by Aaron Sheehan-Dean

Reconstructing Appalachia: The Civil Wars Aftermath

edited by Andrew L. Slap

Moonshiners and Prohibitionists: The Battle over Alcohol in Southern Appalachia

Bruce E. Stewart

Southern Farmers and Their Stories: Memory and Meaning in Oral History

Melissa Walker

Law and Society in the South: A History of North Carolina Court Cases

John W. Wertheimer

RAISING

RACISTS

The Socialization

of White Children

in the Jim Crow South |

|

KRISTINA DUROCHER

THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY

Copyright 2011 by The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth,

serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern

Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky

Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray

State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of

Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University.

All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

www.kentuckypress.com

15 14 13 12 11 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

DuRocher, Kristina.

Raising racists : the socialization of white children in the Jim Crow South / Kristina DuRocher.

p. cm. (New directions in southern history)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8131-3001-9 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-8131-3016-3 (ebook)

1. SocializationSouthern StatesHistory. 2. Children, WhiteSouthern StatesHistory. 3. African AmericansSegregationHistory. 4. Southern StatesRace relationsHistory. I. Title.

HQ783.D87 2011

305.2308909075dc22 2010052272

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting

the requirements of the American National Standard

for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

| Member of the Association of

American University Presses |

C ONTENTS

I LLUSTRATIONS

A CKNOWLEDGMENTS

This book would not have been possible without the help and support of many. The ideas and early research for this project began in graduate school, and I owe a debt to my dissertation advisor, Vernon Burton, for his guidance and support, as well as to the rest of my committee, Elizabeth Pleck, David Roediger, and Jean Allman.

I have enjoyed the complete support of my colleagues at Morehead State University, whose encouragement and assistance have meant so much to me. Tom Kiffmeyer, my mentor, talked me through ideas and read revisions, and I am indebted to him for his insight and time. I am lucky to be surrounded by excellent examples of historians, both as scholars and learners themselves. John Ernst, John Hennen, Tom Kiffmeyer, Alana Scott, and Adrian Mandzy have shaped my expectations and supported my research and writing. Thank you for all your encouragement. Morehead State University awarded me a Research Fellowship in 2007 to assist with research for this project. I was also supported by MSUs Undergraduate Research Fellows. Thank you to Matt Hurley, Chris Wiseman, and James Kyle Hager.

A particular note of thanks to Dr. Thomas Summerhill, who got the ball rolling for me when I was an undergraduate, and to Pete Daniel, for his mentorship and advice.

I would like to thank the University Press of Kentucky, especially Stephen Wrinn, Anne Dean Watkins, and series editor Bill Link, who encouraged this project through revisions and editing. I owe a debt to them for their assistance and patience. I would also like to thank the outside readers for their time and suggestions; your thoughts helped me clarify my ideas and improve the manuscript.

Portions of chapters 1 and 5 appeared in Southern Masculinity: Perspectives on Manhood in the South since Reconstruction, published in 2009 by the University of Georgia Press. I would like to thank them for permission to reprint that material here. A special thanks to Craig Thompson Friend and the readers for their feedback on those sections.

My parents have a love of history that has shaped my own life and career. I would like to thank them for their support. I also would like to thank my husband, who spent the first years of our marriage sharing me with this book. Thanks for all your patience and understanding.

I NTRODUCTION

In this South I lived as a child and I now live. And it is of it that my story is made.

Lillian Smith, Killers of the Dream

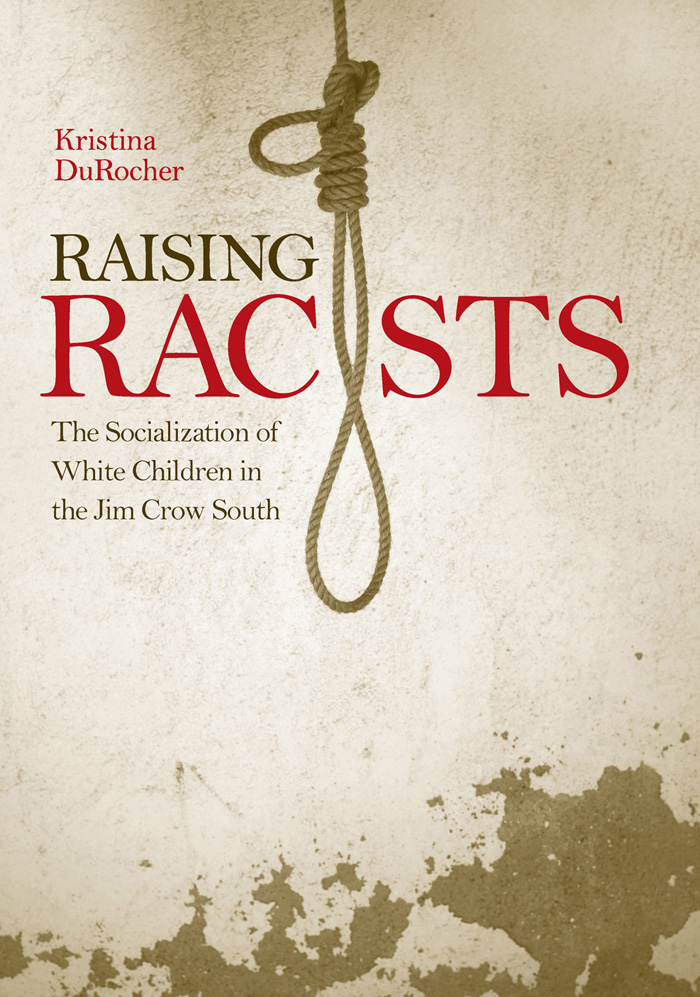

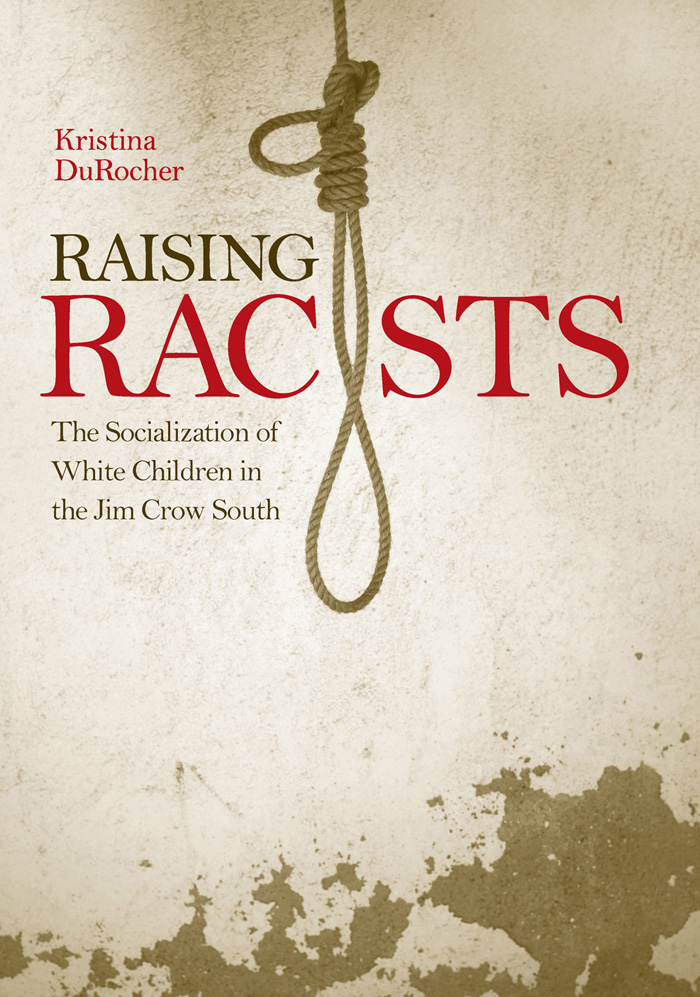

In 1935, a white family traveled to a field in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, to pose for a commemorative photograph with the corpse of African American Rubin Stacy.

Such images and reports attest to the normalcy of white children attending events of racial violence during Jim Crow segregation. Countless other images of lynchings included boys and girls, from a few years old to teenagers, enjoying these public spectacles both during and after the violence. White southern culture in this era accepted and encouraged the presence of white children at scenes of extralegal race-based violence. This became

The lynching of Rubin Stacy, 1935. Courtesy of Picture History.

The lynching ritual offers a microcosm for exploring white southerners conceptions of race and gender, as all members of the white community participated. The role played by white youth in public racial violence has long remained unexplored, as no studies of the Jim Crow South consider this violence as a primary site of the construction of racial identity. Yet white southerners did employ the brutal lynching ritual to construct and maintain southern racial identity, and white children played an active role in the process. Examining white childrens role within the white culture of the Jim Crow South, including its racial violence, reveals the shifting intersections of race, gender, sexuality, culture, and power in the New South. Lynching offered a central public ritual in which white youth encountered and helped to perpetuate the brutal practices that southern white males deemed necessary to maintain segregation and their position at the top of the southern social hierarchy.

Next page