For Robert

With many thanks to the people who helped bring Streets Of Sin to fruition, especially my agent Sheila Ableman, the staff at The National Archives, Metropolitan Archives & RBKC Archives and Mark Beynon and Naomi Reynolds at The History Press.

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

BY JERRY WHITE

Notting Hill! The very name holds magic for us, conjuring before our eyes those strikingly elegant terraces in white or coloured stucco at the ready-to-burst end of Londons hyper-inflated property market. With super-rich property come the people to match. Here are the Russian oligarchs and worldwide billionaires, here are the Hollywood film stars and TV entertainers, the footballers, the celebrity WAGs and fashion models, even the brightest stars of British political life from across the party divide. It was a world unforgettably celebrated in a film of 1999 called what else Notting Hill .

The one thing all of these people must have, it seems, is money. And the other, perhaps, is a love of London, for in part Notting Hill crystallises some of the best that London has to offer its citizens and the world. It still has its council estates that continue to give the area a diverse mix of classes, with working people and the moderately rich rubbing shoulders in street and park and local shops. Just as important, Notting Hill bears the legacy of having been in at the birth of a multicultural metropolis in the years soon after the end of the Second World War. In many ways it was the most important centre in the country of the West Indian diaspora of the 1940s and 50s. For a generation it became the capitals showcase of Caribbean food, music and club life. This legacy has been kept joyously alive in the Notting Hill Carnival, staged here every August bank holiday since the mid-1960s, the largest street festival in Europe, second only to the Rio carnival worldwide, and drawing in between 1 and 2 million visitors each year. Both London and Notting Hill have become even more multiculturally diverse in the last thirty years or so and we can see that in the range of food on offer in Notting Hills restaurants: Indian, Thai, Caribbean, Eritrean, Mexican, American, International, Italian, French, Spanish, Greek, Modern European, British the list seems endless and probably is.

And yet. Scratch the surface, as anywhere, and there are problems. When a world-famous fashion model was reported in the week I am writing this to have had her home burgled, she was described by police as the latest victim of criminal gangs targeting wealthy celebrities in Notting Hill. The easy conjunction of criminal gangs and Notting Hill would jar with many readers, but not with Fiona Rule. For it is this darker tradition of Notting Hill that she has brought to life in her new exploration of Londons seamy side. We might think, and its probably true, that anywhere has its darker side to be unearthed by a sharp-eyed investigator. But what she reveals about Notting Hill will surprise many. For Notting Hills dark side is very dark, and runs very deep, indeed.

Even before what we think of as Notting Hill took shape in brick and slate on the open fields of North Kensington, the district was mired in filth and lawlessness. Part of it was known as The Piggeries and for obvious reasons, the pig-keepers lakes of liquid manure making this the most malodorous suburb in the whole metropolis. Nearby were The Potteries, where colonies of brick makers and potters dug up the local clay and baked it in kilns, their pungent odour and black smoke adding to the districts grime. The fields were dangerous to walk in alone at night, and violent robberies were commonplace. When building did get underway, from the 1860s in particular, the speed and cheapness with which much terraced housing was run up made part of this new suburb, though designed for a smart incoming middle class, notorious as Rotting Hill.

The land on which the piggeries and potteries had held sway, and on which gipsy encampments were a prominent feature, were also eventually developed with housing, even cheaper and worse built and more badly drained than the more prosperous streets. This western part was christened Notting Dale. By the end of the nineteenth century it was one of the most desperately poor and unruly districts of London. Here, bizarrely, was what appeared to be an East End slum at its worst, transplanted to the new smart suburbs of the west. It became for journalists and social reformers in the 1890s and for twenty years after, the West-End Avernus, or hell-on-earth. Over 4,000 people were living here at the turn of the twentieth century. The infant mortality rate in Notting Dale was such that even as late as 1896, forty-three children out of every hundred born there would die before they reached their first birthday.

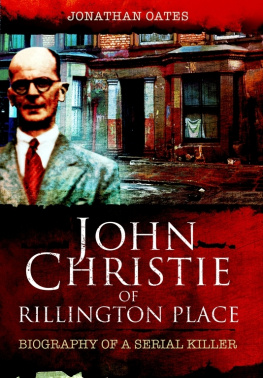

Notorious Notting Dale would remain intact until just before the Second World War; sufficient of it remained in 1958 to help mobilise the worst outbreak of anti-black rioting ever seen in this country, the Notting Hill Race Riots. Close by, at 10 Rillington Place off St Marks Road, one of the very darkest dramas in Notting Hills secret past had been only recently played out. Here between 1949 and 1952, John Reginald Halliday Christie murdered five women and a baby, having killed at least two other women before moving there. He seems to have been a necrophiliac, murdering mainly for sexual gratification. Christie will forever remain the central exhibit in Notting Hills chamber of horrors, as he rightly does in this book.

Christie apart, Fiona Rule has been able to populate Notting Hills sinful saga with a memorable cast list of villains and victims. She has found confidence-tricksters, even slave traders, among the investors of Rotting Hill; there are nefarious doings, including murder, in the blackout and among the spivs of black market Notting Hill during the Second World War; we enter the world of the slum landlord Peter Rachman and meet some of his more famous contacts; we are shown the dreadful murders in the mid-1960s of young prostitutes working the streets of Notting Hill and elsewhere in west London by an unidentified man, so-called Jack the Stripper; and we learn of much else previously hidden away in these overpopulated Streets of Sin.

Through her painstaking investigation, Fiona Rule shows us one by one the skeletons hidden in Notting Hills darkest cupboards. Its all a fascinating story because, as Rule memorably reveals, Notting Hill is that intriguing urban puzzle a glitzy district with a past.

Jerry White

May 2015

Back in the early 1990s, I found myself working in the marketing department of a, sadly, now defunct London bookshop chain. A major part of my job was to attend book launches that were organised by publishers in all manner of interesting and enticing locations. My attendance at these events was supposed to be a fact-finding mission so that I could effectively promote the books in question. However, like virtually everyone else, I generally went for the free wine.

One evening, my boss, who hated these junkets with a passion, thrust a smartly printed invitation into my hand and said, Theres a cook book launch in Notting Hill tonight. Its at the publishers house and I promised her that one of us would go. Clearly, the one of us was going to be me.

As I sat on the Central Line train heading towards Notting Hill Gate, I realised that I was venturing into a part of London about which I knew virtually nothing. As a staunch north Londoner, my social life rarely took me further west than Marble Arch and the only thing I associated with Notting Hill was the annual carnival, which, according to the press, was so dangerous that no one in their right mind would want to go there. The train rumbled into the station, I alighted and made my way out into the sunlight. It was a glorious, late summer evening and the atmosphere as I stepped on to the broad, shop-lined thoroughfare exuded a calm that never permeated the endless hubbub of my West End workplace. I checked the address on the invitation and after consulting my AZ, made my way towards Ladbroke Road.

Next page