Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

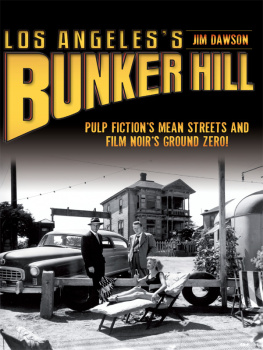

Copyright 2012 by Jim Dawson

All rights reserved

Cover image from the film Cry Danger. Courtesy of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences.

First published 2012

e-book edition 2012

ISBN 978.1.61423.578.1

print ISBN 978.1.60949.546.6

Library of Congress CIP data applied for.

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

CONTENTS

Los Angeles detectives Glenn Ford and Ricardo Montalban stake out the old Brousseau place on Bunker Hill Avenue in The Money Trap (1966). Courtesy of Warner Bros.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks to Rick Mechtly for generously sharing his deep knowledge and Sanborn maps of Bunker Hill; to Nathan Marsak, Marc Wanamaker and Earl Reinhalter for their invaluable assistance; to Richard Schave and Kim Cooper for keeping noir Los Angeles alive; to Thom Andersen and John Bengtson for their archeological inspiration; and to the late photographers Arnold Hylen, George Mann and William Reagh who so beautifully documented Bunker Hill during its last decades. Id also like to thank Mary Katherine Aldin, Susan Arosteguy (Criterion Collection), Lynne Bateson, Leonard Bernstein (Caravan Book Store), Bob Birchard (American Film Institute), Claire Brandt (Eddie Brandts Saturday Matinee), Kathleen Correia (California State Library), Byron Dillon, Dino Everett (USC School of Cinematic Arts), Art Fein, Bill Kay, Marianne Leach (California State Library), Gary Leonard, Mary Mallory (Motion Picture Academy of Arts & Sciences), Jeff Mantor (Larry Edmunds Books), Eddie Muller (Film Noir Foundation), Tony Nittoli, Gordon Pattison, Paul Politi, Robert Porfirio, Ray Regalado, Christina Rice (Los Angeles Public Library), Alan K. Rode, Phil Stufflebean, Andy Schwartz, Alain Silver, James Ursini, Alexx VanDyne, John Welborne (Angels Flight Railway Foundation), Ian Whitcomb and last but most certainly not least, Dianne Woods.

INTRODUCTION

In his 2003 film documentary Los Angeles Plays Itself, Thom Andersen observed, In a city where only a few buildings are more than a hundred years olda place can become a historic landmark because it was once a movie location. Thats only a slight overstatement. An iconic film thats loved by millions or worshiped by a determined few can turn the most prosaic street or structure into a cultural reference point. Pilgrims from all over the world will come to visit as if something really happened there.

To a location nut like me, the quality of the film is often beside the point. One early morning not long ago, I was watching a 1941 B movie called Double Cross, produced by a Santa Monica Boulevard slum operation that disappeared decades ago. If I told you the actors names, you wouldnt recognize them. Like most cheap indies of that era, Double Cross was shot mostly on rotting studio sets left over from the early talkies. Just sitting through it was a slog. But then, just as I was ready to give up and go to bed, the screen brightened to a distant white sunlight as a motorcycle cop rode up to a parked car on what looked like a Hollywood residential street. The cars owner, a woman, came out of an apartment building whose ground-floor facade had a simple Egyptian or Mayan design. Suddenly, as the camera panned down the street, I recognized where they were. At the end of the block was a distinctive three-story art deco tower that still stands today at 5620 Hollywood Boulevard. I put the DVD on still, pushed my feet into my shoes, ran out to my car and hurried the short distancelittle more than a milefrom my Beachwood Canyon digs to the Sir Launfal Apartments still standing at 1848 North Gramercy Place, just below Franklin Avenue. The next-door Tudor homes in the film were gone, replaced by 1950s apartments, but the front of the Sir Launfal was unchanged.

As I stood in the same spot as those long-dead ghosts frozen at that very moment on my TV screen, I felt like Id made some physical connection with the past, as if the gravity of the Sir Launfal had momentarily folded time in on itself. Or at least thats how it seems on a dark and misty early-morning street youve only just visited seventy years ago, before you were even born.

Living in Hollywood, Im accustomed to stepping into movie history. The long hillside stairway leading up from 2744 Westshire Drive to the 2800 block of Hollyridge Drive, where Kevin McCarthy and Dana Wynter fled from the townspeople in the original Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956), is a three-minute stroll from my front door, and I frequently hike up or down its 149 steps. If I choose to go in another direction along Beachwood Canyons western ridge, within twenty minutes Im walking past 6301 Quebec Street, the hillside Spanish Colonial exterior of the house where Fred MacMurray said, Goodbye, baby, and shot Barbara Stanwyck in Double Indemnity (1941). (As a bonus, novelist James M. Cain, who wrote Double Indemnity, once lived in a French-Norman house just up the hill from me in the 2900 block of Belden Drive, flush with the road, so that any passing pedestrian can glance into the corner sunroom where he probably wrote Mildred Pierce.)

But one famous location I cant visit is Bunker Hill. Oh, I can go downtown and stroll the charmless pedways and concrete parking caverns of a fortress called Bunker Hill, but its Bunker Hill in name only, not the Bunker Hill. Except for the Second Street tunnelnow one of L.A.s busiest locations for car commercialsand the older Third Street tunnel; the sealed-off Pacific Electric subway tunnel running diagonally beneath them; a funny little incline railway that was moved half a block from its original location; the stocky 1938 zigzag deco Southern California Edison Building at Fifth and Grand (dubbed One Bunker Hill); a couple of large 1920s office buildings near Fifth and Hill; and a section of the old Fremont Hotels stone wall on Olive Street just below Fourth, that wonderful, sprawling movie set called Bunker Hill has been struck. Knocked down and hauled away to distant landfills. Even its little railway, Angels Flight, was mothballed in warehouses for nearly thirty years before they brought it back and put it in the wrong place. Simply put, Los Angeless mandarins set out to obliterate Bunker Hill as resolutely as the Enola Gays bombardier leveled Hiroshima. You cant even stand on a street corner today and point your finger and say, That house was right hereunless youre pointing straight upbecause they lopped off the original hilltop just like the army turned Elviss pompadour into a buzz cut back in 58. Then they laid down a new grid of streets stacked on top of each other and planted Los Angeless first skylinea vertical maze of steel, marble and opaque, palladium-silver glassdeep enough within the hills guts that in some places their piles punctured the old subway tunnel. If you want to see the original Bunker Hill, youre out of luck, unless youre satisfied with two-dimensional representations: paintings, photos, postcards, a handful of novels and short stories and several dozen old movies and TV shows.

Next page