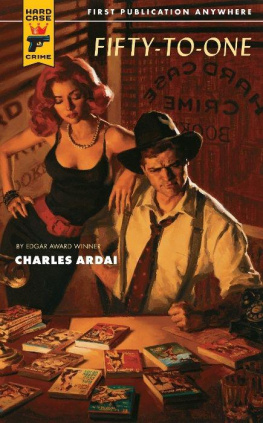

State paranoia and paranoid states in the fiction of David Goodis, Chester Himes and Jim Thompson

The origins of detection; the privatization of the investigatory process; the politics of Philip Marlowe, Lew Archer, Paul Pine and Mike Hammer; wages, conditions and inflationary tendencies of fictional private eyes

The portrayal of women in pulp culture fiction; women hardboiled writers; Leigh Bracketts The Tiger Among Us, Dolores Hitchenss Sleep with Strangers and Dorothy B. Hughess In aLonely Place as tacit critiques of a male-oriented genre

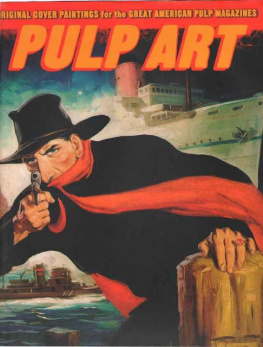

Pulp is the Warmest Colour

Back in 1966, I was living in France and my limited knowledge of crime fiction was restricted to Agatha Christie and Mickey Spillane. I had grown up a keen fan of science fiction and fantasy, attracted by its unlimited sense of wonder and my youthful self saw Christie as enjoyable if derivative, a perfect, uninvolving way of whiling away a few hours reading without overly engaging the brain whileas Spillane books (and others in its wake) offered a confused appeal due to their troubling promise of sex and matters sexual I could only guess at. It was then that Le Nouvel Observateur serialised Jim Thompsons Pop. 1280 to celebrate the legendary Srie Noire reaching its thousandth title. I had never heard of Jim Thompson before. Reading the excerpts I came to the conclusion that this was crime writing as I had never come across before, shockingly crude, realistic and disturbing, and it ticked a box in my imagination.

Less than two years later I was back in London without investigating the matter further as my priorities in life finally became to change and I became less of a bookworm and was awakened to certain realities involving the opposite sex and its splendours. When a decade or so later I entered the murky waters of book publishing, I was faced with a new set of realities and when in the early 1980s I was offered the opportunity to run my own publishing outfit, financed by the music industry, one of my first priorities was to explore genre fiction and return to my literary roots. However, after a quick survey, I came to the conclusion that the SF & fantasy field had, to my disappointment, been thoroughly mined (the idea had been to resurrect forgotten classics as my editorial budget precluded publishing new material). It was then that a spark lit up and I recalled Jim Thompson and following a bout of research discovered that, in France, he was just the tip of the iceberg. So many other names, all American, who were selling huge quantities of books in French to significant critical acclaim, and they all appeared to be long out of print in the UK and the USA, and in frequent cases, had never actually been published on our shores! I returned from a trip to Paris with a suitcase full of second hand books and plunged into a whole new world of words.

David Goodis, Cornell Woolrich, Horace McCoy, William P. McGivern, Robert Finnegan, Charles Williams, Dolores Hitchens, Gil Brewer, and so many others opened my eyes to a whole new dimension of genre writing the Anglo-Saxon world had somehow managed to ignore. I was astounded. This was writing from the gut, writing that changed lives.

How could such a vital stream of American writing have come and gone and been largely ignored? It was as if I was opening a Pandoras box of subversive delights, where every old / new writer I pulled out led me to yet another and in due course, would even reveal contemporary talents who had similarly been concealed in the metaphorical darkness like Marc Behm, Derek Raymond in the UK, Jerome Charyn and others.

I resolved to publish them all. Needless to say in many cases it became a gargantuan effort not only to obtain copies of the books in their original language but then to track down the rightful copyright holders through begging contract executives at publishing houses to scour their archives for my benefit, hunting down relatives and family survivors or even banks and long-retired literary agents and lawyers. To this date, no one has yet established who controls the rights to the wonderful Robert Finnegan late 1940s trio of stunning left-wing hardboiled novels and he remains unpublished as a result, which is a major loss to our appreciation of crime writing of that period.

The books began to appear to wonderfully complimentary reviews, albeit to only moderate sales. For a decade or so, it became my mission in publishing (aside from issuing countless cookery and gardening books, rock biographies, fitness and computer titles so that the companies I ran stayed afloat) to mine this seemingly inexhaustible vein of writing, from Black Box Thrillers onwards to the Blue Murder imprints. Quickly filmmakers beyond France began to take notice, younger English-language crime writers rediscovered the sources of their inspiration and, inevitably, American fans and editors jumped on the bandwagon when Barry Gifford adapted the idea to launch the Black Lizard list in the USA with most of the writers and titles I had previously uncovered to which he added a further batch of forgotten authors he had come across, as I had, in his youth. The iceberg of noir was being uncovered inch by inch and it was a veritable treasure trove.

Soon, major publishing houses inevitably began to lure the Estates away and giving some of the authors an even wider audience where we, smaller independents, could not. It felt as if a whole occult strand of literature, let alone crime writing, was being revealed. It was a great time.

A quarter century later, it is now self evident that Goodis and his cohorts were the true heirs of Chandler and Hammett, and its not just the wonderfully perverse pulpdar of French intellectuals who recognise the fact. A whole new generation of writers, within as well as outside the crime genre, has since been heavily influenced by the goldmine I and my fellow travellers in literary archeology brought to light and crime writing as we now know it has moved aeons beyond Agatha Christie and the universe of cosy.

Its now fascinating to analyse the reasons, not so much for the sheer quality of these authors, why these writers were seldom appreciated in their lifetime and Woody Haut points us to the economic realities of the age of paperback publishing and the political and social context against which these books were written and their authors struggled to get their voices heard. His analysis is faultless and fascinating and his approach is both that of a fan, with enthusiasm bubbling under the surface, and an academic in its forensic attention to the facts, albeit without the cold detachment that academia sometimes brings to bear on a given subject.

Few critics have looked as closely at what I would proudly claim was an undeniable literary movement, disparate, scintillating, all-encompassing and beyond the sociological and literary detective work Haut has so successfully completed, what PULP CULTURE does is make us want to to read these books all over again as new fascinating facets are brought to light that make a new reading not only compelling but obligatory. And I say this as someone who had to read many of the books under consideration more than a dozen times each on average, through the reading process, the editorial stages, the proofreading and now see how much I missed!