This 2005 edition published by

arrangement with Robert Lesser.

Published by Sterling Publishing Co., Inc.

387 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016

1997 by Robert Lesser

Distributed in Canada by Sterling Publishing

c/o Canadian Manda Group, 165 Dufferin Street

Toronto, Ontario, Canada M6K 3H6

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise,

without prior written permission from the publisher.

Sterling ISBN 14027-3035-7

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Manufactured in China by Midas

Acknowledgments

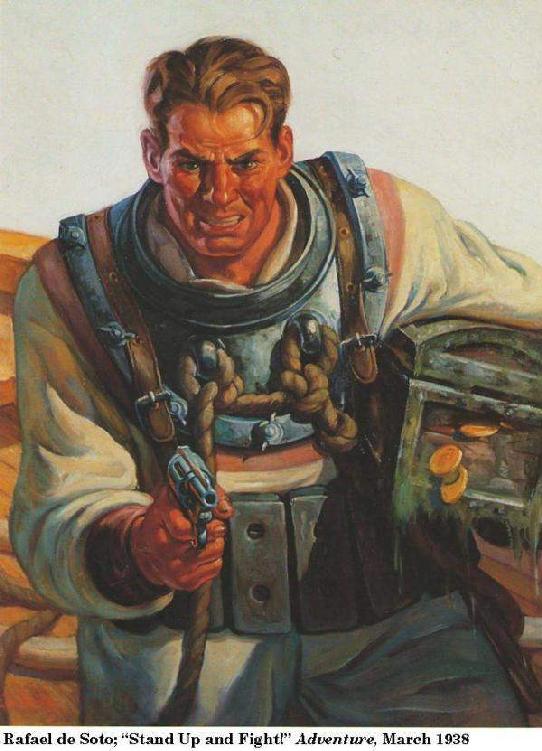

The author wishes to express his unreserved gratitude to the following contributors, pulp-art scholars and collectors, and editors and designers for their help in making this book both possible and very special: Forrest J. Ackerman, Sam Moskowitz, Shirley Steeger, Steve Kennedy, Robert Weinberg, Fred Cook, Walker Martin, James Van Hise, John Locke, Capel N. McCutcheon, Albert Tonik, Jack Deveny, Charles G. Martignette, George Berger, Joseph Gaspari, Carolyn Naporlee, Jim Steranko, John de Soto, Zina Saunders, Danton Burroughs, Darrell C. Richardson, Charles Crane, Robert Barrett, Walt Reed, Roger Reed, Will Murray, Alison M. Scott, Linda Dobb, Rush Miller, Norman Brosterman, Geroge Hocutt, Bruce Cassidy, Ray Bradbury, Tom Lovell, Roger Nelson, John McLaughlin, Tom Johnson, John Gunnison, Frank Hamilton, Tony Goodstone, Richard Merkin, Rafael de Soto, Pierre Boogaerts, Anthony Tolin, Clarence Peacock, Gene Nigra, Mel and Stephen Korshak, Ralph Kaschi, Peter Garriock, Paul Herman, Bob Hyde, Richard Greene, Lyn Hickman, Rusty Hevelin, George Hagenaur, Jerry and Helen de la Ree, Jane and Howard Frank, Randall Hawkins, Phil Weiss, Bruce Bergstrom, Frank Robinson, Jack Juka, Jerry Weist, Thomas Horvitz, Daniel Mark Fay, Cole Springer, Jerry Schattenburg, Grover DeLuca, Leonard Robbins, Ben Chapman, Leon Sevilla, Robert Hammerquist, David Kimball, Russ Cochran, Bill Thailing, Don Hutchison, Beverly and Ray Sachs, Irma Rudin, Herm Schreiner, Peter Manesis, Dino Petrocelli, Bill Morse, Dr. Alfred Collette and Domenic J. Iacono of Syracuse University, David Alexander, Gloria Stoll Karn, Joseph Di Lessio, Dennis East, Jim Gerlach, Bradleigh Vinson, Sheldon Jaffery, Nick Carr, Robert Sampson, Gary Lovisi, Henry Steeger, William Papalia, Mike Avallone, William Feeny, Frederic Taraba, Joe Parente, Ryerson Johnson, Emil Petaja, Norma Dent, Peter Osborne, George McWhorter, Victor Dricks, Frank J. Finamore, Helene Berinsky, and Gregory Suriano.

There is the theory in current political aesthetics that a work authored by only one person is a fascist work of art because it dictates a single point of view; refuses to permit the inclusion of a democratic sampling of important facts unknown to the single author; and ignores creative insights that could illuminate dark corners and increase the body weight of information. This theory is accepted here. Other voices are happily and proudly included in this book. They are those who should be thanked for having collected, studied, created, and preserved an inheritance of art for future generations to enjoy. Interspersed throughout the text are superb and insightful essays by those who have lived and breathed the pulps for decades.

Contents

ESSAYS

ESSAYS

ESSAYS

ESSAYS

ESSAYS

ESSAYS

Introduction:

Populist Culture

and Pulp Art

I n the United States of America there never has been and never will be Tyrants of Taste commanding us to like what we dont, to whisper yes when we want to shout no. For hundreds of years kings and queens forced our forebears to bend their knees and shut down their minds, to accept their concepts of high culture and to be ashamed of popular concepts of low culture. Inherited titles without the merit to match, enrichment of power derived from laws bought from the political peddlers they put in place, and the capturing of the worlds riches enabled this small elite to dictate the absolutes of culture.

The lot of the Americans is singular: they have derived from the aristocracy of England the notion of private rights and the taste for local freedom; and they have been able to retain both, because they had no aristocracy to combat.

Alexis de Tocqueville,

Democracy in America

But on March 4, 1789, things changed. On March 5, the ink on the Constitution dried and populist culture was born. Now any American was free to sing any song, paint any picture, write any story, pay his money to see, hear, and buy what he liked, without any prince or priest wedged in between. Hidden inside the Constitutions Section 9 was a Declaration of American Cultural Independence and an Aesthetic Bill of Rights. From this extension of liberty, won by war and revolution, we have taken the political permission to be pleased.

No title of nobility shall be granted by the United States: And no person holding any office or profit or trust under them, shall without the consent of Congress, accept of any present, emolument, office or title of any kind whatever from any king, prince or foreign state.

The Constitution of the

United States of America, Section 9

Up from this fertile soil of American political liberty has flowered a unique cultural anarchy granting the absolute freedom of anyone to choose anything. All of us are free to pay admission or stay home, to turn it on or turn it off; and we are free to love this or hate that, to collect or reject without a fine-arts professors permission or the wax seal of approval from the elite of a major metropolitan museum.

This anarchic dimension of liberty has no limits because each new generation is free to begin it all over again, enraging parents, shocking seniors, and allowing things old-fashioned to temporarily wither away by refusing to purchase any of it.

Europes elite culture is institutionalized: opera in Italian, ballet la Russe, classical music in a tuxedo, and paintings of antique faces of the rich and royal of centuries past. But in the United States of America, culture is patronized and chosen with its dollars; beneath it all is the belief that the best will never be because the best is yet to come. Many of us dislike frozen culture because it is always the same. Newness is a major attraction of populist culture: youve never seen it before, never heard it before.

In this nation, art and technology have fallen madly in love and enjoy a happy mixed marriage, and their offspring amaze and delight. And with startling speed this union has produced a materialist extension of democracy: the anarchy of ownership. Just a few years ago Hollywood had all the movies clutched in a tight fist and might release a classic once every few years. But with the invention of the VCR and videos, anarchy has been extended into ownership, and now all of us own all of it. Soon the finest art from the finest museums in the world will be ours by pressing a fingertip on a computer key. The entire corpus of world culture, past, present, and deep into the future will be owned by the poorest man in the smallest home.

Next page