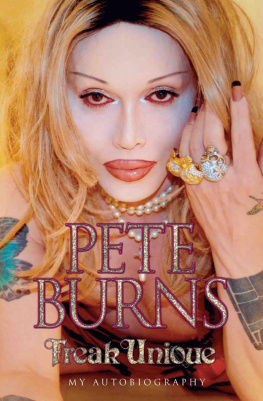

FREAK OUT

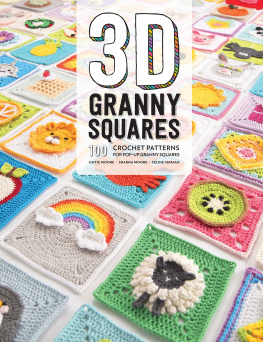

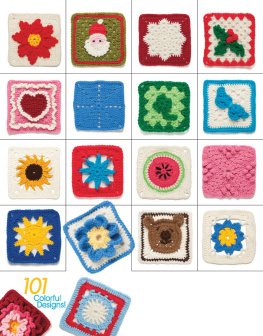

THE SQUARES

Contents

Picture credits

2011

SHEFFIELD

On the bus with Gareth and Ralph. The bus is a camper van. It has a wobbly little table with four seats, a sink and a fridge, which we do use, and a toilet which we dont. In the back are two long padded seats that face each other, which you could lie down on but arent supposed to in transit. It is nominally a six berth, but that would be very snug. It does however have a button that makes a pair of stairs mysteriously emerge from the side: very James Bond.

Gareth is the driver, I have only met him once before. He was down at the rehearsal rooms when I was styling them, helping to put up the giant neon P.U.L.P. signs. He did this in a curious way using complicated knots and fastenings.

Me: You a climber, mate?

Gareth: No, caver.

Me: Got lots of anecdotes about caving?

Gareth: Yeah, quite a few.

Me: Know much about minerals?

Gareth: Yeah, a fair bit.

Me: Do you drive?

Gareth: Yes.

Me: Do you want to drive me on tour?

I had presumed Gareth was one of the many roadies who periodically turned up at the rehearsal rooms in preparation for the tour. As I found out later, he was just someones mate hanging about and had never encountered the crazy world of rock and roll before. You wouldnt have known it to look at him. With his Mott the Hoople straggle cut, Maglite, extra-length shorts, reckless climbing skills and dissolute air he had all the hallmarks of pondlife. Pondlife is road-crew slang for lighting engineer: presumably because, however depraved road crews may be in general, lighting engineers always take it that much further into the swamp.

On the road you spend a lot of time in close proximity with those you are working with, and a ready supply of anecdotes can enliven an otherwise dull journey, as well as diffusing the inevitable cabin fever that will set in. Gareth seemed like a good egg, but could just as easily have been a maniac.

Now here he was skulking about in front of my house in Sheffield, about to drive us thousands of miles in a rickety little charabanc, enjoying a crafty toke of special relaxing herbal tobacco. Not the ideal start, but in the grand scheme of things not a biggie. What was I going to do? Pull out of the tour?

Ralph is my manager/stylist/carer for this tour. When the prospect of the Pulp tour came up we were writing an ill-advised musical about the miners strike and he took on the managerial role by default.

I had first seen Ralph many years before, swanning around town in a purple suit, trilby hat and lightning-strike sideburns. Typical student, I thought: all outrageous now, when outrageousness is conformity, give it a couple of years and hell be kowtowing to The Man as if it had all never happened.

A couple of years later, he was running the much-loved club Razor Stiletto, from which he picked up the moniker Ralph Razor. I ran into him next at a Saxon concert he was promoting. Saxon were the model for the fictional band Spinal Tap and it was for this reason, rather than any deep-seated love of heavy metal, that Ralph was putting them on. He was wearing pink winkle-pickers. He invited me to his thirtieth birthday party, which I had expected to be populated by mwa-mwa hairdresser types it wasnt. It was in an old casino and Ralph was sat on a throne wearing a full Marie Antoinette dress and pompadour wig with a model galleon on top, surrounded by Russian girls who called him Meester Ralph. The cat had style.

What I do is play guitar and violin in the band Pulp. I am on the way to my first concert engagement in fifteen years. This is a long time of absence. Im not a fan of reunions in general but somehow this one feels okay at least in principle.

How did it happen?

Well, a couple of years previously, Pulps singer Jarvis had rung me up out of the blue and said: Do you want to play Glastonbury?

Me: Ooh, I dont know about that, Im not really keen on reunions.

Jarvis: Just the one show.

Me: Well, we can talk about it.

Jarvis: Okay, Ill ask the others, see what they think.

Glastonbury was the scene of our perceived greatest triumph and stands outside the general world of touring, having an exalted semi-mystical status. People will put aside their differences for Glastonbury and play football in no-mans-land before going back into their trenches. It was tempting and, as I had left Pulp in circumstances that I still resented, it seemed like a way to attain some kind of closure on the whole unfinished business.

Well, the months passed and no return call came (not atypical this). It was well past the moment we would have needed to prepare for a show, so I booked my holidays elsewhere for the time of Glastonbury, to make it impossible to be tempted to cobble something shoddy together at the last minute we owed it to The Kids.

The phone rang.

Jarvis: Are you still up for playing Glastonbury?

Id mentally rehearsed my response (Fuck off, followed by phone slam). But I couldnt resist the jibe

Me: Youve left it a bit late, mate, Glastonbury was weeks ago!

Jarvis: No, no, next year: Ive talked to the others and theyre up for it.

Me: Oh, next year. Oh, right: well, I suppose we could talk about it.

We arranged to meet at Nick the drummers house in Sheffield for the summit. Everyone was nervous, but on best behaviour. Jarvis and I kept popping out for cigarettes to postpone the inevitable encounter.

I had left the band acrimoniously fourteen years earlier, at the peak of its fame. They had continued for another seven years, recording another two albums and touring, before it all petered out. In the intervening time, posteritys assessment of Pulp had been kind and there was, it seemed, a demand for us to play concerts. I had my reservations: there was something glamorous about quitting at the height of success and to go back now might seem a sell-out. My life had moved on and I hadnt picked up a guitar for years.

I was proud of my time in Pulp and quit before I could become one of those crozzled-up old rock stars doing the circuit, not knowing when to stop. I got out well before hitting forty at which age, in my opinion, pop stars who dont know when to quit should be pushed off a cliff in the Brigantian fashion, for the greater good of the tribe.

By now I was fifty, carrying a pound or two too many, and had a bad back: youd think there was an obvious answer to the question of a reunion. But there was something nagging. The end had seemed premature; wed struggled for years to get to a high point. Id done all the transit van load-your-own-gear hard work and had barely stayed around to enjoy the success.

The original proposal had now expanded from one concert to ten and my doubts increased, where would all this end? I had no intention of getting back onto the treadmill permanently and the nostalgia circuit was complete anathema to me.

As it turned out, what was being proposed was not some Relive the glory days of Britpop and sing along to your old favourites, but rather a summer tour of European festivals, which is about the most fun you can legally have on the road. And The Kids go to festivals, not just middle-aged ladies in feather boas who ought to know better; and apparently The Kids dug us. I had kids they were little when I was last doing this, now they were grown-up they didnt listen to Pulp.

When my son was little, he once said, You used to be cool, Dad!

Thinking he was being ironic, I said, Oh yeah, when was that then?

Flatly he replied, as if explaining the obvious to someone with that forgetful thing you get when youre old, When you were in Pulp.

Next page