TO the British in the early twentieth century India was nothing short of the jewel in their crown, the most glorious and important colony of the empire.

When the British Crown took over direct control from the East India Company in 1857 it inherited over 750,000 square miles of territory. For whatever ills India suffered at the hands of colonialism, the enduring legacy of Britain was the railway system it built to connect the wide-ranging cities dotting the vast countryside. In its heyday the Indian rail network was the largest on Earth. Besides being a practical way to transport goods, the trains were also widely used by the British colonials.

Each railway system, such as the East India Railway Company or the Bengal Railway Company, was independently owned and operated. While the railways were a visual symbol of the British Raj, or rule, they were also vehicles of national unity. The trains helped distribute food in times of famine and opened up trade. More importantly, they were the greatest private employers in India, hiring both men and women of all castes. The rail companies also built hospitals and schools for employees and offered company housing. Working for the railway was considered the best job in government service. For the British railway managers life in India was positively royal. The East India Railway town in the Jamalpur district had swimming pools, tennis courts and also a Masonic Lodge; even the managers lived in palatial company houses.

By the early twentieth century the Indian rail system was thriving, but new tracks were continually being built and the need for British engineers remained high. In 1925 a tall, slender young man from Doncaster, Yorkshire, named Louis Rigg came to answer a job listing in the Times newspaper. Previously, Louiswho was called James by his friends and familyhad won a scholarship to become an engineering apprentice and was anxious to find a job. Just twenty-two and coming from a lower middle-class family, Louis was willing to travel halfway around the world for a chance to work in exotic India for a good wage and steady employment.

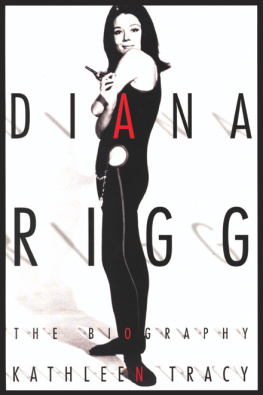

Louis spent five years in India before returning to England. While relaxing at a local tennis club, Louis met a young woman named Beryl Helliwell; they fell in love and when it came time for Louis to return to India, Beryl accompanied him. They were married in Bombay Cathedral in 1932 and moved into a bungalow at Bikaner, located in the state of Rajasthan, situated on Indias western border. Two years later Beryl gave birth to a son they named Hugh, who was born in a military hospital. Four years later she got pregnant again, but this time she traveled to Britain for the birth of their second baby, Diana. Diana Rigg would later comment that her mother had such a terrible experience at the military hospital during Hughs birth that she insisted on returning to England to deliver her second child. Plus, England must have seemed a very appealing way to avoid the brutal Indian summer heat. On July 20, 1938 Diana Rigg was born in the South Yorkshire town of Doncaster. Just two months later Beryl returned to India to rejoin her husband and young son.

The colonial India of Dianas childhood provided for an exotic upbringing. Both Bikaner and Jodhpur, where her family moved in 1943, are filled with magnificent palaces and forts, remnants of earlier times when other states posed the threat of invasion. They are perched at the edge of the Thar Desert, also known as the Great Indian Desert, and during the summer temperatures regularly reach 115 degrees. Anyone with the means would head to the hills during the sweltering summers. Despite the heat, the landscape held a harsh beauty. There are no oases or artesian wells in the Great Indian Desert, so there are no native cacti decorating the landscape, which alternates between sand, scrubby hills and gravelly plains. But there is abundant reptilian wildlife, with dozens of thriving lizard and snake species, which the Riggs and others living in the region learned to avoid.

Tall and slender, Diana was a tomboy as a child and says, For Hugh and I India was a wonderful adventure but with some frights for my mother. She shrieked if we went out without our topis, and there were snakes everywhere, particularly in the bathrooms. The gardener showed us a snake nest once and we saw the babies in their eggs.

Diana remembers living in a big house. We had gardeners and what were called servants in those days. It was very British Raj. In terms of the Raj hierarchy, though, my father wasnt high up the ladder. But they used to go to astonishing banquets at the palace. Ive still got the menu cards. My mother would describe some exquisite confection on her plate, made from spun sugar. I remember how she said, I simply had to tap it with my spoon for it to shatter, it was so delicate.

Diana and her brother lived near the railways; they grew up in the shadow of the majestic train stations where beggars and British aristocracy alike waited to board. Of course, the cabs used by the sahibs and memsahibs (as wealthy Europeans were called) were starkly different from those used by the poor. Rigg would later recall, We went to the hills in the hot season much as the Royal Family travels to Balmoralin our own carriage, referring to the plush private rail cars they rode in. Now that their engineer father had risen through the ranks to railway superintendent, they were afforded the comforts and advantages that came with the position. I remember the smell of oil and metal. This was Dads kingdom. He loved it so much.

Summers were spent in Nainital, an area in the Himalayan foothills also called the Lake District. Mother allowed us to run wild, Diana told the London Daily Telegraph in a 2002 interview. We disappeared every day, though we came back for lunch. I remember sucking the toffee my mother used to make, reading Jim Corbetts Maneaters of Kumaon with the rain thundering on the roof. And I remember my father reading Kipling to me. Diana recalls her father reading to her Kiplings Just So Stories and Tolkiens The Hobbit. India gave me a glorious start to life. It gave me an independence of spirit. Our parents lived very social lives and took us on lovely family outings.

The rest of the year was spent in Bikaner. Their house was a bungalow, which is actually derived from the Hindi word bangle, roughly translated as house in the Bengali style: a one-story home with a low, pitched roof. Weve come to think of bungalows as being small and cozy, but the family home in India was spacious and came complete with a fireplace. Although the temperatures soared in summer, the winter evenings were cool. Outside, there was a large front lawn, where Hugh could play cricket with local boys or he and Diana could spend the afternoon riding ponies.

Like many other British families in India, the Riggs had several servants and Diana was cared for by a nanny, called an ayah, who taught her Hindi. The ayah would say, aap bahut hi badmash ladki hainyoure a very bad girland my mother told me I talked like an Indian, Diana recalled to Trevor Fishlock during a trip back to India in 2002. My mother tried to keep things English and gave us the nearest thing to English food, a lot of it from tins and disgusting; although her sardine kedgeree was delicious. Remembering the nanny and the servants, Rigg recalls wistfully, They all spoiled me.

Although Louis had been born without means, his job at the railway had brought him financial success and prestige. As a result, Louis and Beryl found themselves moving in ever higher social circles among the British in India. It was a social leap for both of them, Diana told Fishlock. Mother had to learn quickly to run a house with servants and adjust to the social conventions of the Raj, which were strict and without mercy or pity. But they lived happy lives of privilege. Dad was an excellent shot and a brilliant golfer, tennis and squash player. These qualities made him welcome. And he was also a witty, handsome man with great social ease. Rigg also recalls that her dad liked to fish, a hobby she would take up years later as an adult, noting she is quite good at seeking out the gentlemans fish, the one that isnt actually sitting up and begging to be caught.