TRAVELS IN ATOMIC SUNSHINE

Robin Gerster is a professor in the School of Languages, Literatures, Cultures and Linguistics at Monash University. He is the author of several books, including the award-winning study Big-noting: the heroic theme in Australian war writing (1987); the travel book Legless in Ginza: orientating Japan (1999); the critical anthologies Hotel Asia (1995) and On the Warpath (2004), and Pacific Exposures: photography and the Australia-Japan relationship (2018), co-authored with Melissa Miles.

His articles have been published extensively in scholarly journals in both Australia and abroad, and he has been a frequent writer of travel pieces for newspapers and magazines.

Scribe Publications

1820 Edward St, Brunswick, Victoria 3056, Australia

2 John St, Clerkenwell, London, WC1N 2ES, United Kingdom

3754 Pleasant Ave, Suite 100, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55409, USA

First published by Scribe 2008

This edition published 2019

Text copyright Robin Gerster 2008

Afterword copyright Robin Gerster 2019

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publishers of this book.

9781925849370 (Australian edition)

9781912854448 (UK edition)

9781950354030 (US edition)

9781925113204 (e-book)

Catalogue records for this book are available from the National Library of Australia and the British Library. the National Library of Australia.

scribepublications.com.au

scribepublications.co.uk

scribepublications.com

To Bill Gater and Teruaki Fujishiro

an old soldier

lodged in our house

tells a war story

that says nothing

about killing an enemy

Zenmaro Toki

What else is there in Japan? Old men making pots

moulded of ash from the bomb,

bearing MacArthurs thumbprint.

Elizabeth Riddell

Contents

Introduction :

Part I

Gulliver in Lilliput: Japanese travails

Part II

Occupation Blues: disturbing the peace

Part III

Japanorama: on tour

Part IV

Embracing Japan: conquest and contact

Conclusion :

INTRODUCTION

Occupying Japan

In Hiroshima, they say that the best view of the fabled isles of Japans Inland Sea is to be had downtown, from the Sky Lounge on the 33rd floor of the Rhiga Royal Hotel. It seems a tactless thing to call something in Hiroshima, of all places oblivious to the bolt from the blue that struck just after 8.00 a.m. on 6 August 1945, when the Enola Gay flew across the sky of a perfect summers morning and dropped a 4000-kilogram atomic bomb called Little Boy, incinerating the city and much of its population. Nevertheless, the bar attracts tourists as well as drinkers. The panorama is indeed spectacular, although on a day of dazzling sunshine the distant islands appear to sit on the sheen of water like lumps of molten and solidified metal.

The spectators gaze settles first on Miyajima, lying just off the mainland in Hiroshima Bay. Armies of sightseers are ferried there daily, paying their respects to the ancient Shinto shrine Itsukushima, with its photogenic vermillion torii, which, seeming to float out at sea, provides an idealised image of Japan as familiar as snow-capped Mt Fuji. At low tide, visitors are disappointed to find the enormous structure rooted in a field of wet mud. The island itself has been venerated for centuries. Once, neither birth nor burial were permitted to defile its sacred ground. Expectant mothers were shunted off to the mainland and remained there for weeks, for purification after delivery. Even today, burial and cremation are prohibited; they bury or burn their dead on the opposite shore. Adjacent to Miyajima, tiny Ninoshima is as associated with death as the other island is with life. During the chaotic aftermath of the atomic bombing, thousands of the grievously suffering made their way to the island to die. They perished in caves, or on open ground; the corpses were so numerous that the customary cremation rites were dispensed with and bodies were piled into vast burial plots. Mass graves were excavated as late as the 1970s. A little further east lies Etajima, the home of the Imperial Naval Academy and a short boat trip from the naval base at Kure, Japans most important since the 1880s. Etajima miraculously survived the American aerial attacks that gutted the Chugoku region of southwestern Honshu during the weeks leading up to that cataclysmic moment when Little Boy both wiped out Hiroshima and forever placed it, notoriously, on the world map.

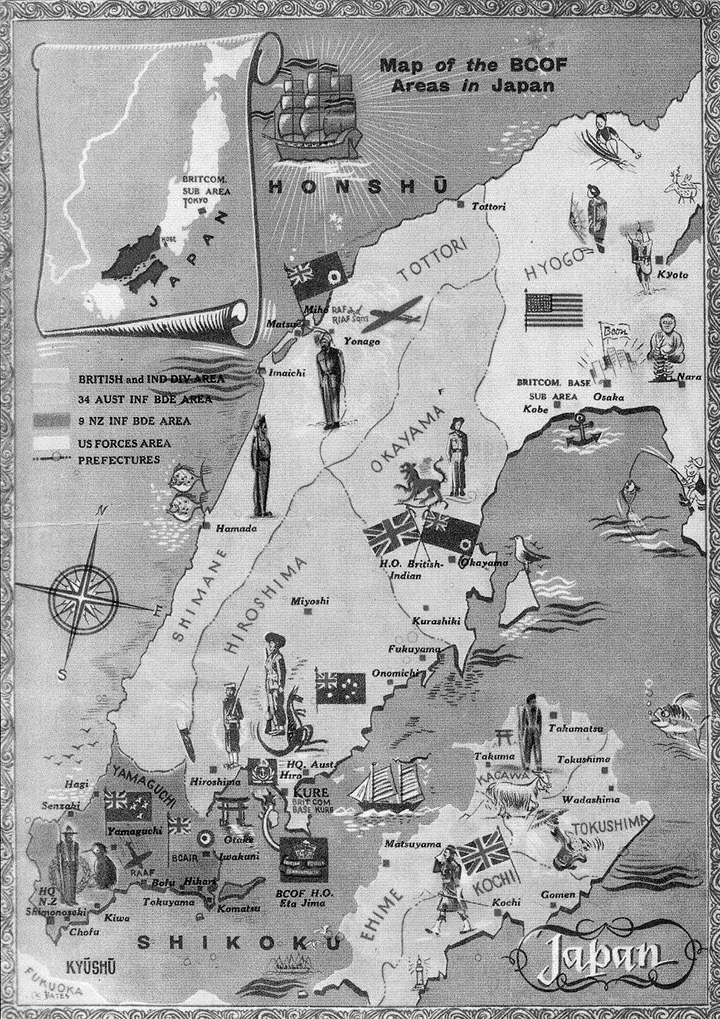

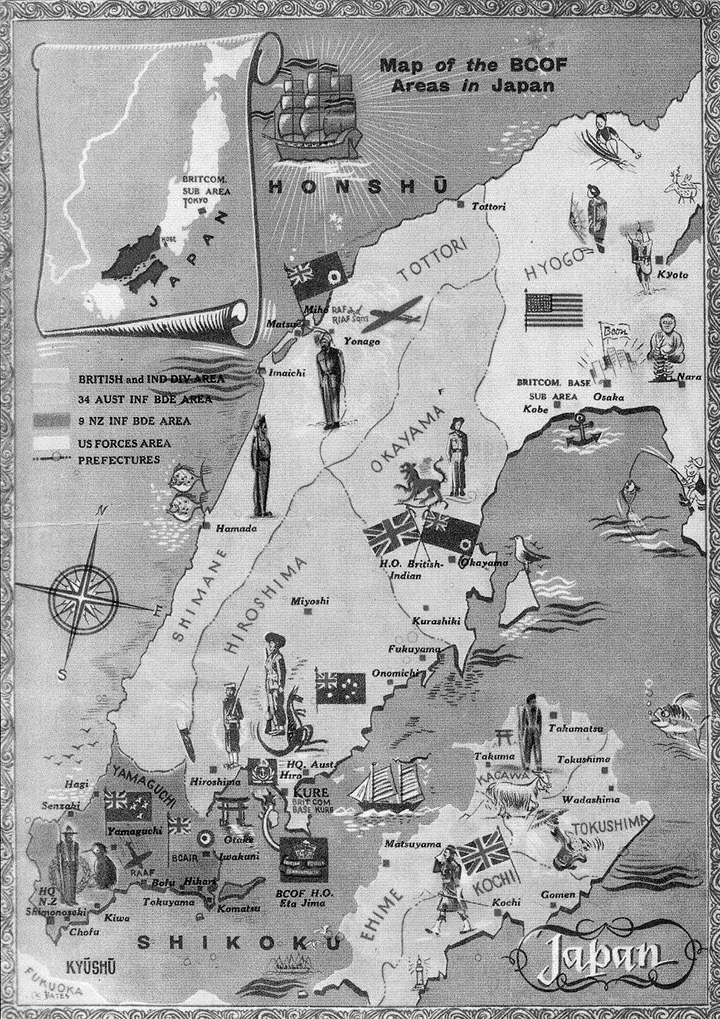

The new and terrible weapon as the Japanese emperor Hirohito described it in mid-August 1945, when accepting the Allies demand for an unconditional surrender did the job for which it was intended. Six months later, the men of the British Commonwealth Occupation Force (BCOF) were handed the task of demilitarising and democratising the remote and ravaged Hiroshima region. The omnipotent ruler of post-war Japan, the United States, had gifted it to its wartime allies, none of whom was more enthusiastically committed to the occupation of its recent and still deeply despised enemy than Australia. BCOF entered a literally explosive environment for, when the war ended, the islands of the Inland Sea were honeycombed with tunnels containing thousands of tonnes of sequestered ammunition, armaments, and deadly chemicals, some of which had not yet been located and destroyed. On the mainland, the ruin and despair were pervasive. Orphans had made homes in wreckage; people were living on their wits, or however they could. The only thing to thrive was prostitution. After their wartime travails, the Occupationnaires, most of them veterans of the bloody conflict that had just been brought to such an abrupt conclusion, appeared to have arrived at the end of the world.

The first convoy of the Australian contingent of BCOF disembarked at Kure in early February 1946. Volunteers in the national military tradition, they had come from the tropical swelter of the battle theatres of the South-West Pacific into the fag end of one of the bitterest Japanese winters in history. The nip in the air, as some of the men were amused to call it, seemed to be matched by the cool indifference of the Japanese welcome. To a young West Australian soldier, T.A.G. Hungerford, the arrival was one of pure tourist bathos. The day-long journey up the Inland Sea aboard the SS Stamford Victory had seemed like a voyage though an illustrated brochure called Beautiful Japan: a day in the Thousand Islands: the seas sparkled, the gulls wheeled, little fishing vessels bobbed in the wake of the troopship. But Kure was a letdown: young Australians who had dreamt of a noisy, triumphal conquerors welcome arrived at a city that had taken a terrific pounding by Allied incendiary bombing. Dry-docks and warehouses had been reduced to rubble; the harbour was a shipping graveyard, a morass of twisted metal. They marched into a silent city. Sidewalks and roads were deserted; winter temperatures had plummeted to record lows. Nonplussed soldiers trudged to their billet through a Dali landscape of solids blasted and melted and seared into eerie plastic shapes of petrified flame, and bedded down in a plaster-and-lath former office block whose doors had been blown out and windows blown in.

Distant Hiroshima and its desolate surrounds were a world away from Occupation General Headquarters (GHQ) in central Tokyo. Much of the wooden-built capital had been obliterated by the ruthless American firebombing of 910 March 1945, an urban holocaust that consumed 100,000 lives and left more than a million homeless. But the fashionable uptown areas of pre-war Tokyo, around Ginza and Marunouchi, were surprisingly intact. From here, the US set about reconstructing and redeeming the Japanese with a missionary zeal democratising the hell out of them, as one cynic observed. The epicentre of American power was the suite of offices of SCAP, the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, General Douglas MacArthur. These were situated on the top floor of the neo-classical Dai-Ichi Mutual Life Insurance building, pointedly overlooking the moat of the Imperial Palace , in an enclave dubbed Little America. The Americans redrew the very cartography of Tokyo to make themselves feel at home, after their arrival in September 1945. Soon, the old military parade grounds in Yoyogi would be taken over for family housing and renamed Washington Heights. Senior officers resided in Frank Lloyd Wrights Imperial Hotel, located on a boulevard redesignated First Avenue , just along the way from MacArthurs HQ. At the famous, endlessly photographed intersection in Ginza, the elegant Hattori building was converted into a PX, the Eighth Army Post Exchange, selling tax-free consumer goods to the cashed-up GI, from cameras to diamond rings. At the PX grill, he could feast on Coke, milkshakes, hot dogs, French fries, and (in a nice touch) B-29 burgers.

Next page