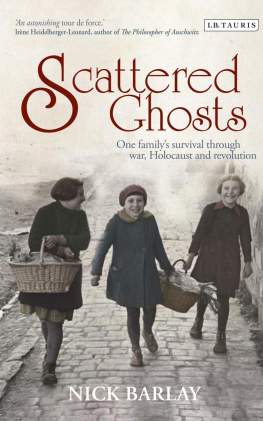

Nick Barlay is the author of four acclaimed novels and was named as one of Grantas 20 best young British novelists in 2003, until it was discovered he was too old to be young. Born in London to Hungarian Jewish refugee parents, he has also written award-winning radio plays, short stories and wide-ranging journalism. www.nickbarlay.com .

Praise for Nick Barlays Fiction

Nick Barlay is a fine chronicler of Londons grittier sub-cultures.

Time Out

Rarely does one read writing so inventive, yet so tensed against habituation brilliantly literary.

Alex Clark, The Guardian

Funny and melancholy ultimately thought-provoking This writer has thought about the country we live in and how it got to be the way it is.

Hilary Mantel

Barlays controlled and energetic demotic fixes you to the page superbly bitter-sweet a fine literary novel.

Daily Telegraph

Praise for Scattered Ghosts

Between fact and fiction, archival research and genealogy, Nick Barlay re-enacts the torments of Hungarian Jewish history from the Holocaust to 1956 and to exile in London, where he was born to refugee parents. He takes us to the margins and the cracks, the streets, the houses and the cellars. His tale is an astonishing tour de force , it is a memorial to the unsung heroes through the prism of his family: compelling and informative, deeply moving and scrupulously understated.

Irne Heidelberger-Leonard, author of The Philosopher of Auschwitz

An intriguing and moving narrative. Barlay writes calmly, but with feeling. The fortunes of a Jewish family during the Holocaust and the Communist rule in Hungary come across powerfully and ultimately with a dash of optimism.

Ladislaus Lb, Emeritus Professor of German, University of Sussex, and author of Dealing with Satan: Rezs Kasztners Daring Rescue Mission

Is it family history? It is. Is it poetry? It is that, too charming poetry. But clouds soon darken the scene. Theres the smell of blood and the tumult of Arrow Cross pogroms. What binds these family fates together is fine writing and Hungarian cherry strudel.

Peter Fraenkel, translator, broadcaster and author of No Fixed Abode: A Jewish Odyssey to Africa

Published in 2013 by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd

6 Salem Road, London W2 4BU

175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010

www.ibtauris.com

Distributed in the United States and Canada Exclusively

by Palgrave Macmillan

175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010

Copyright 2013 Nick Barlay

The right of Nick Barlay to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978 1 78076 662

eISBN: 978 0 85773 457

A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

A full CIP record is available from the Library of Congress

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: available

Text design, typesetting and eBook by Tetragon, London

To my father, Stephen Barlay

19302010

and to my family, past and present

Contents

Knock upon yourself as if upon a door and walk upon yourself as if upon a straight road.

Silvanus

I was there too that night, said my brother. Youve airbrushed me out.

Robin Barlay

Ne piszkld ezt a dolgot. Remnytelen. (Leave this thing alone. Its hopeless.)

Bandi Gmri, second cousin

Ghosts

The Knock

I TS A RECURRENT DREAM, them turning up.

One dark and stormy night, goes this dream, when I am snug under a duvet, protected from wind and from rain, there is a knock at the door. I ignore this knock, attributing it to the dream, to a dream within a dream, or an imagined knock, or a melodrama brought on by years of conditioning, a cultural assault of dark and stormy nights and knocks on doors.

But, of course, the first knock is followed by a second, the second by a third, and on until, so goes this dream, I am awake. Conscious, partly, I connect the knuckle at the door to some midnight hoaxer or some giggling bingers crabbing their way home. But, of course, the knocks continue, more insistent still, louder still, even threatening, as if more than a jest, more like a solitary madman sent by some malign occult force to mess with my slumber. So a battle of wills begins: to respond or not, to do something or not. And eventually, in this dream, unable to ignore the knocking, unable to sleep, I find myself going to the door.

I open it a crack, just to catch a warning glimpse of a face. Instead of one face or even two, there are twenty or thirty, a proper crowd, a silent crowd. Its difficult to count the heads, in the dark, during a storm. The crowd could be forty-strong, to say nothing of all the bits, all the stuff, all the luggage that they seem to have brought with them, their unwieldy bags, their weather-aged suitcases, their last-minute bundles, their unleavable heirlooms, their wayfarers essentials stuffed into pockets. There they patiently stand, their stout shoes mud-encrusted, their coat-tails spattered, their hat brims dripping rain. Its obvious this isnt a lynch mob or a pack of debt collectors. There is no anger in them, no menace. They do not loom. There is only hope in their faces the hope, perhaps, that they can get out of the wind and the rain. But why here? Why me?

As I squint, the answers to these questions come into focus. I begin to recognize them, at least one or two or three or half a dozen among them. There is the one who was kissed by an emperor. There is the one who interviewed statesmen, and over there the one who almost died rich, another whose assets were dust. Theres the religious one, the one who went mad, and the one who committed suicide. There are the two who had strange accidents. And the one who went missing but came back, another who disappeared, never to be seen again. Then theres the one who danced, the one who played the piano, the one who wrote. Then there are the ones who were taken away and killed.

I recognize them because I have met them, some in life at close quarters, a few at a distance when the moon was blue. The rest I have met in albums, in yellowed photographs and faded snaps or in brown envelopes containing special portraits that were lost and found and lost again. Now, they have turned up at my door en masse, together, as if someone had planned it, wearing the very clothes that they wore in the pictures, that they have always worn or seemed to wear.

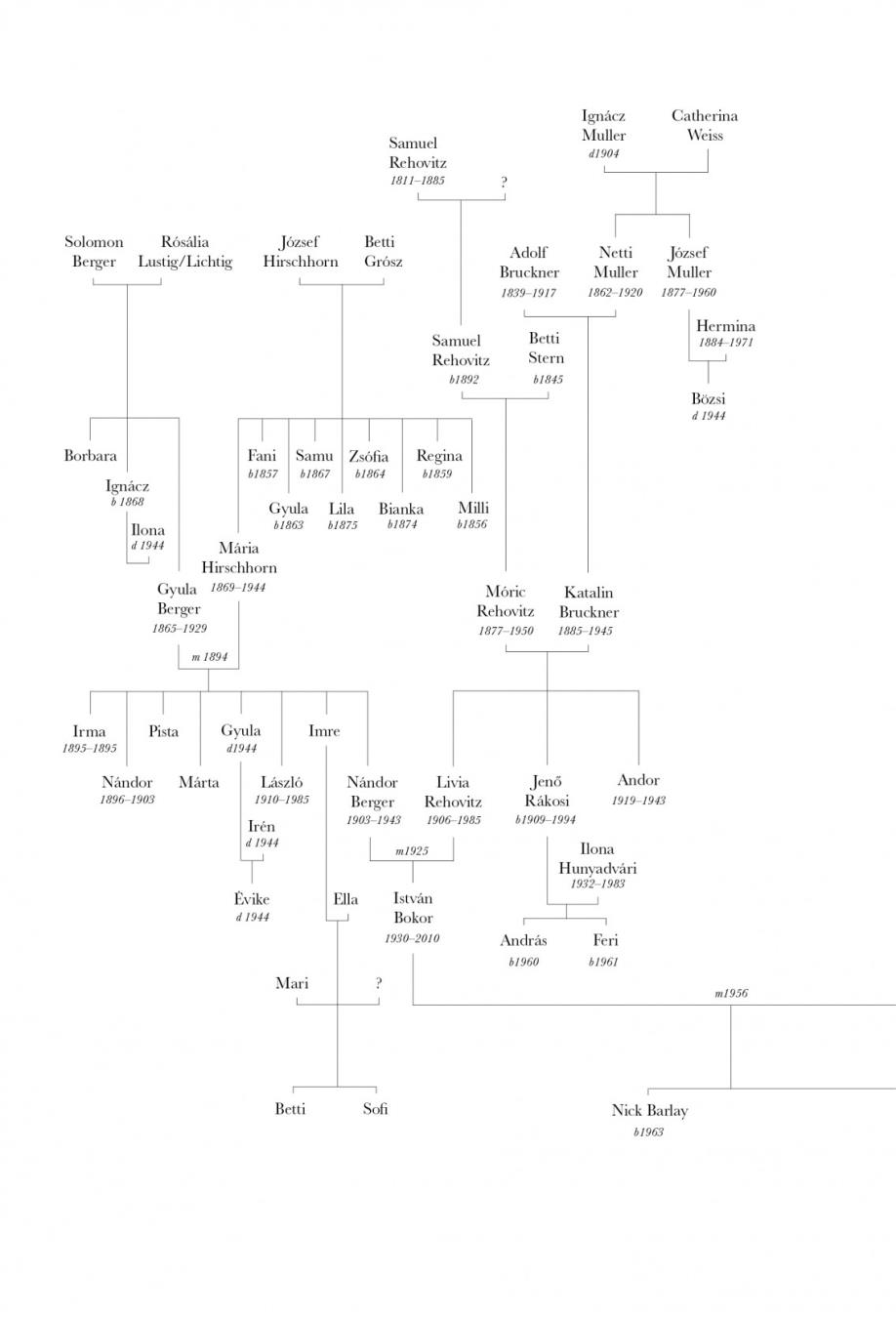

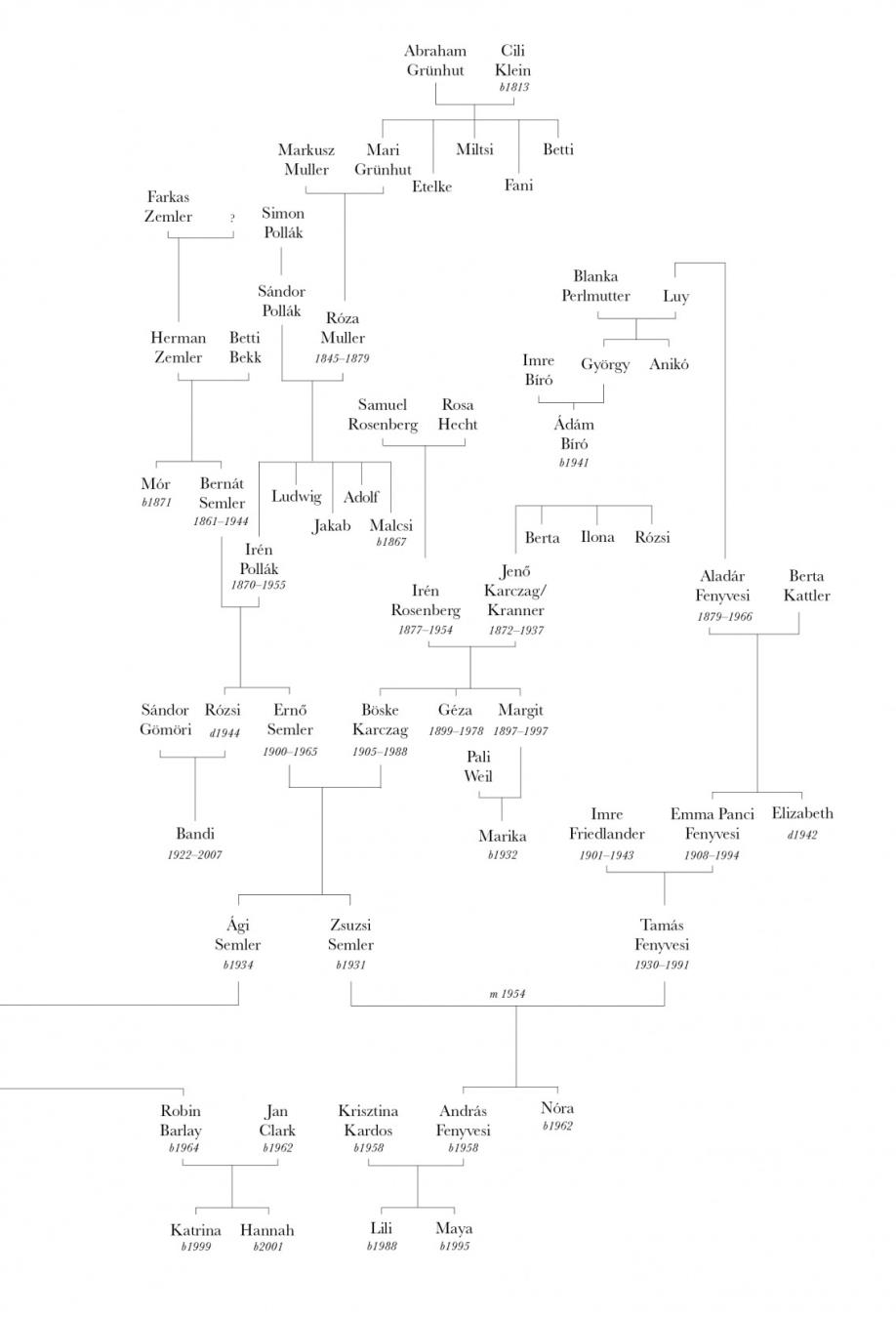

As I pull the door further open, theyre waving papers at me flaking documents, delicate and rarely unfolded certificates, stamped passes, special authorizations, counter-signed exemptions, official permits as if to prove that were connected, that they have a peculiar right of entry granted by some long-dead functionary on behalf of a long-gone administration. And in this dream, in accordance with some obscure small print, they have arranged themselves alphabetically. There are the Bergers, the Brs, the Bokors and the Bruckners, then Diamantborn, Fenyvesi, Finkelstein and Friedlander, Gmri, Hirschhorn and Karczag, followed by Kranner, Mller and Pollk, with Perlmutter and Rehovitz just ahead of Rosenberg, Semler and Stern, and finally Weil and Zemler at the rear.