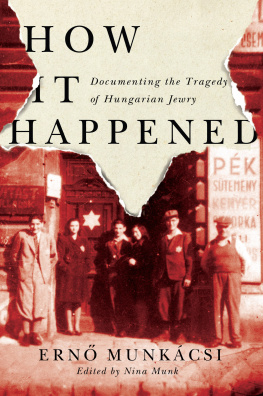

Praise for A GUEST IN MY OWN COUNTRY

An East European might say that George Konrds adventures through two terror regimes and a major revolution have been what one would expect from someone unfortunate enough to have been born in that part of Europe. In reality, Konrds autobiography reveals much more than that: great tragedies, fabulous escapes, a complex personality, a great writer and beyond that, dignity and courage in the worst of circumstances. I STVN D EK , Professor Emeritus of history at Columbia University; author of The Lawful Revolution: Louis Kossuth and the Hungarians, 1848-1849

Konrd takes you into another country. Another world. His words allow you to feel his world. In intimate and luxuriant detail. The world of childhood, the world of war, of politics, of hatreds. The world of words and of longing. In illuminating his country, his world, Konrd illuminates our world. L ILY B RETT , author of Too Many Men

Konrds prose was never so luminous as in these moving yet clear-eyed and forthright recollections of his wartime childhood, his youth and early manhood under Communism, and of his life as a writer in the soft dictatorship and after. I VAN S ANDERS , translator, literary critic, and Adjunct Professor at Columbia University

Emerging from the pen of a premier Hungarian intellectual, and spanning several turbulent decades, this vivid, unsentimental, candidly intimate memoir gives us an invaluable view of a complex history, and of a very Eastern European fate. Konrds affectionate recollections of his childhood; his astonishing account of growing up precociously at war; and his sharply etched vignettes of repression and dissidence, poverty and pleasures thereafter, are marked by grace amidst turbulence, honesty without bitterness, and by an admirable balance between skepticism and deep attachments. An important, illuminating, and ultimately hopeful book. E VA H OFFMAN , author of Lost in Translation and After Such Knowledge

Part I copyright 2002 by Gyrgy Konrd

Originally published in Hungarian by Noran, Budapest, 2002, as Elutazs s hazatrs.

Part II copyright 2003 by Gyrgy Konrd

Originally published in Hungarian by Noran, Budapest, 2003, as Fenn a hegyen napfogyatkozskor.

The author has approved the abridgment of Part II.

Parts I and II translation copyright 2007 by Other Press

Production Editor: Mira S. Park

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from Other Press LLC, except in the case of brief quotations in reviews for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast. For information write to Other Press LLC, 2 Park Avenue, 24th Floor, New York, NY 10016. Or visit our Web site: www.otherpress.com.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Konrd, Gyrgy.

[Elutazs s Hazatrs. English]

A guest in my own country : a Hungarian life / by George Konrd; translated by Jim Tucker; edited by Michael Henry Heim.

p. cm.

Pt. 1. Originally published in 2001 as Elutazs s Hazatrs. Pt. 2. Originally published in 2003 as Fenn a hegyen napfogyatkozskor.

eISBN: 978-1-59051-495-5

1. Konrd, Gyrgy. 2. Authors, Hungarian20th centuryBiography. I. Konrd, Gyrgy. Fenn a hegyen napfogyatkozskor. English. II. Tucker, Jim. III. Heim, Michael Henry. IV. Title.

PH3281.K7558Z46 2007

894.51133dc22

[B] 2006024280

v3.1

Contents

I

Departure and Return

FEBRUARY 1945. WE ARE SITTING ON a bench in a motionless cattle car. I cant pull myself away from the open door and the wind whipping in off the snowy plains. I didnt want to be a constant guest in Budapest; I wanted to go homea weeklong tripto Berettyjfalu, the town our parents had been abducted from, the town we had managed to leave a day before the deportations. Had we stayed one more day we would have ended up in Auschwitz. My sister, who was fourteen, might have survived, but I was eleven, and Dr. Mengele sent all my classmates, every last one, to the gas chambers.

Of our parents we knew nothing. I had given up on the idea of going from the staircase to the vestibule to the light-blue living room and finding everything as it had been. I had a feeling I would find nothing there at all. But if I closed my eyes, I could go through the old motions: walk downstairs, step through the iron gate, painted yellow, and see my father next to the tile oven, rubbing his hands, smiling, chatting, turning his blue eyes to everyone with a trusting but impish gaze, as if to ask, We understand each other, dont we? In a postprandial mood he would have gone onto the balcony and stretched out on his deck chair, lighting up a long Memphis cigarette in its gold mouthpiece, looking over the papers, then nodding off.

For as long as I can remember, I had a secret suspicion that everyone around me acted like children. I realized it applied to my parents as well when, not suspecting us of eavesdropping, they would banter playfully in the family bed: they were exactly like my sister and me.

From the age of five I knew I would be killed if Hitler won. One morning in my mothers lap I asked who Hitler was and why he said so many terrible things about the Jews. She replied that she herself didnt know. Maybe he was insane, maybe just cruel. Here was a man who said the Jews should disappear. But why should we disappear from our own house, and even if we did, where would we go? Just because this Hitler, whom my nanny followed with such enthusiasm, came up with crazy ideas like packing us off to somewhere else.

And how did Hilda feel about all this? How could she possibly be happy about my disappearing, yet go on bathing me with such kindness every morning, playing with me, letting me snuggle up to her, and even occasionally slipping into the tub with me? How could Hilda, who was so good to me, wish me ill? She was pretty, Hilda was, but obviously stupid. I decided quite early that anything threatening me was idiotic, since I was a threat to no one. I was unwilling to allow that anything bad for me could possibly be an intelligent idea.

For as long as I can remember, I have felt like the five-year-old who ventured all the way out to the Beretty Bridge on his bicycle and stared into the river, a mere eight or ten meters wide in summer, twisting yellow and muddy through its grassy channel, pretending to be docile but in fact riddled with whirlpools. That boy was no different, no more or less a child than I am today. In spring I watched from the bridge as the swollen river swept away entire houses and uprooted large trees, watched it washing over the dike, watched animal carcasses floating by. You could row a boat between the houses: all the streets near the bank were under water.

I felt that you could not count on anything entirely, that danger was lurking everywhere. The air inside the Broken Tower was cool, moldy, bat-infested. I was frightened by the rats. The Turks had once laid siege to it and finally taken it. This is a wild region, a region of occupations: myriad armies have passed through it; myriad outlaws, marauders, haiduks, and bounty hunters have galloped over its plains. The townspeople take refuge in the swamps.

My childhood recollection is that people had a slow way of talking that was expansive and quite cordial. They took their time about communicating and expected no haste in return. The herdsmen cracked the whip every afternoon as they brought the cows home. Then there were the Bihar knifemen: cutting in on a Saturday-night dance could mean a stabbing.