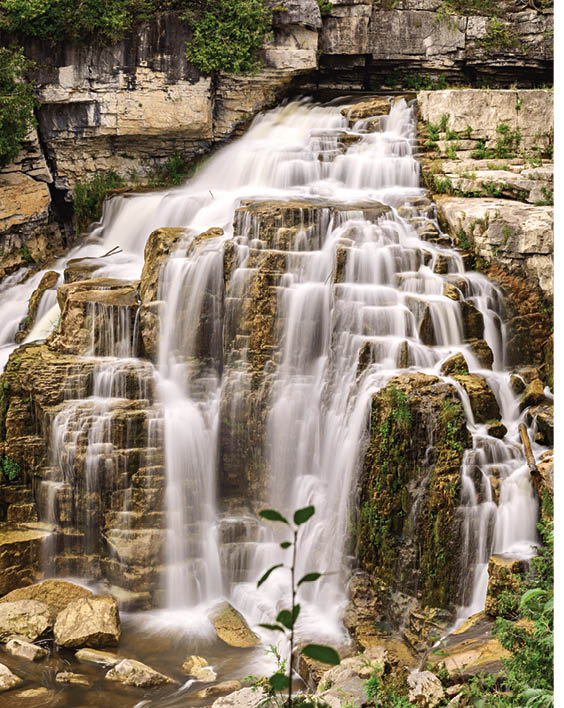

A typical waterfall along the Niagara Escarpment.

Inglis Falls Conservation Area near Owen Sound.

A lookout point on Manitoulin Island. See Route 19.

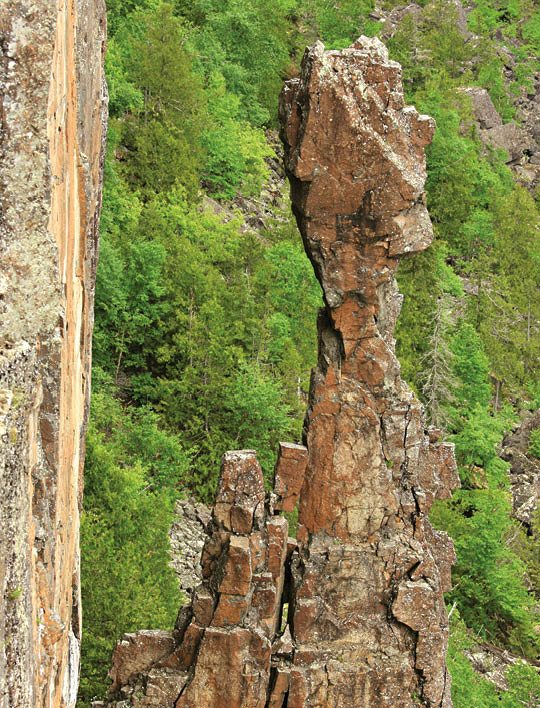

Indian Head at Ouimet Canyon Provincial Park near Dorion, Ontariosee Route 21.

Todays backroad adventures are a far cry from 1837, when traveller Anna Jameson wrote the above words. Indeed, thanks to those who flee the hustle of freeways and the tedium of suburban sprawl to seek the tranquility of an uncluttered countryside, backroad driving is North Americas most popular outdoor activity.

This book leads you from Ontarios main highways onto its backroads. Before 1939, the province had no expressways. That was the year King George VI and Queen Elizabeth opened the Queen Elizabeth Way. In 1929, Ontario had less than 2,000 km of hard-surface highway. Before 1789, it had no roads at all. European settlement of Ontario began with the arrival of the United Empire Loyalists from the war-torn colonies that had become the United States of America. The Loyalists settled on the shorelines of the St. Lawrence River, Lake Ontario and Lake Erie, and they had no need of roads. But the governor of the day, John Graves Simcoe, casting a wary eye on the restless neighbour to the south, embarked on the building of military roads. In 1793 he ordered a road from Montreal to Kingston, and Ontario soon had its first road. (You can follow it even today as County Road 18 through Glengarry County.) This he followed with Yonge Street and Dundas Street, which also survive and have retained their names.

Despite the slow pace of settlement through the early years of the 19th century, the pattern of Ontarios road system was taking shape. From the Loyalist ports roads led inland to bring out lumber and farm products. They were useless quagmires in spring and little better in summer. Only in winter, when frost and snow combined to create a surface that was hard and smooth, did farmers haul their wheat to port.

Settlement roads connected the main towns of the day. Among the more important were the Danforth Road, replaced soon after by the Kingston Road (portions of both survive), linking York (now Toronto) with Kingston; the Talbot Trail that followed the shores of Lake Erie; and roads to the northwest, such as the Garafraxa Road, the Sydenham Road and Hurontario Street.

As settlement progressed, surveyors made their way through the forests, laying out townships and surveying each into a rigid grid of farm lots and concessions. Along each concession they set aside a road allowance, linked at intervals of 2 to 5 km by side roads. And so Ontarios road network became a checkerboard that paid no attention to mountains, lakes and swamps.

One of the first problems was that there was no one to build the roads. Although each settler was required to spend twelve days a year on road labour, settlers were few at first.

In the 1840s, the government turned road-building over to private companies and to municipalities. Some of the companies tried such improvements as macadam and planks. But rather than being grades of crushed stone, the macadam was often little more than scattered boulders, while the planks rotted after a few years. When the railways burst on the scene in the 1850s, road companies and municipalities both turned their energies to railway-building.

Despite the railways, the government tried one more road-building venture, the colonization road scheme. This was in the 1850s, when lumber companies were anxious to harvest the pine forests that cloaked the highlands between the Ottawa River and Georgian Bay. Although early surveyors had dismissed the agricultural potential of the upland of rock and swamp, the government touted the region as a utopia for land-hungry settlers. What the politicians didnt reveal was that the main aim of the scheme was to provide labour, horses and food for the timber companies. Once the forests were razed and the timber companies had gone, the settlers who had moved to the area were left to starve. By 1890 most of them had fled, and the roads in some cases were totally abandoned. Nevertheless, a few of them retain their pioneer appearance and have become some of the backroads in this book.

In 1894 the Ontario Good Roads Association was formed to lobby for better roads, and in 1901 the government passed the Highway Improvement Act to subsidize county roads. Finally, in 1915, the government got back into the business of road-building and created the Department of Highways. The first 60 km of provincial road was assumed east of Toronto in 1917.

But for decades afterward, northern Ontario remained railway country. Most towns and villages north of the French River owed their existence to the railways, and what roads there were stabbed out from the railway lines to the lumber and mining camps.

The years following the Second World War saw the arrival of the auto age, and during the 1950s and 1960s Ontario embarked on a spate of road improvements unequalled in the entire previous two centuries. Road-building continues unabated, and as it does it destroys much of the provinces traditional landscape. As rows of maple and elm, cedar rail fences, and roadside buildings fall before the bulldozer, Ontario is left with a legacy of endless asphalt. Despite enlightened planning, countryside sprawl continues to engulf Ontarios once pastoral landscapes. It is not surprising, therefore, that Ontarians, overwhelmed with the tedium of an omnipresent suburbia, are travelling farther afield to seek the tranquility of backroad Ontario.

The backroads in this book are special. Each has a story of its own. Some follow the unhappy colonization roads, some the more prosperous settlement roads; some explore rural areas that have retained their century-old landscapes, others follow the shores of lakes or rivers. Some plunge into deep valleys and mount soaring plateaus. Others take you into northern Ontario to logging areas old and new, to once-booming silver fields and to the fringes of the provinces last frontiers.