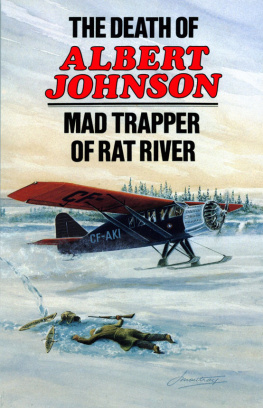

The Legendary Chase

Saturday, December 26, 1931

A few hours before daybreak on Boxing Day, 1931, Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) Constable Alfred King and Special Constable Joe Bernard harnessed a team of sled dogs and mushed west from their Arctic Red River detachment in the Northwest Territories, at the confluence of the Mackenzie and Arctic Red rivers. They were heading out to investigate an accusation made by Aboriginal trappers who lived and worked along the Rat River that someone had been interfering with their traplines.

The man in charge of the Arctic Red River detachment, Constable Edgar Millen, knew that the only newcomer to the area of late was a taciturn trapper known as Albert Johnson, who had arrived the previous summer. In July 1931, Millen had spoken to this man in a store at Fort McPherson. He had noticed that the newcomer seemed to be carrying a large amount of money and also that he seemed very quietbut not so much as to cause concern, especially in a time and place where eccentricities were common. He also noticed that the stranger spoke with a trace of a Scandinavian accent.

Constable Millen introduced himself to Johnson. Police protocol in this remote area was to make sure everyone within the jurisdiction was mentally and physically prepared for the arduous conditions of the extreme north. The constables exchange with the stranger was cursory, and had it been his only interaction with Johnson, the young officer might never have given the mans existence another thought. About a month later, however, Millens commanding officer, Inspector Alexander Eames, sent him a stern written rebuke, taking him to task for not having questioned the man calling himself Albert Johnson as thoroughly as he should have.

Furthermore, since the initial encounter in July, the newcomer had shown himself to be not just an uncommunicative and unfriendly person, but also an uncooperative one who had not purchased a trapping licence. This factor further fuelled suspicions that he might be the one guilty of interfering with his Aboriginal neighbours traplinesa serious accusation, as families livelihoods depended almost exclusively on the sale of pelts.

However, one officers later research revealed that the Aboriginal trappers accusations might not have been truthful. RCMP Constable William Carter investigated the original complaint in the spring of 1932 and found an entirely different story. Evidently, Johnson had roughly told them to take off and had even pointed a gun at them, when they came a-visiting at Johnsons cabin.

Carters report goes on to say:

Knowing Indians very well, I can imagine they were curious about Johnson and wanted to know what he was doing in their trap area. Also, it is customary to give an Indian a drink of tea and something to eat. With repeated visits, Johnsons food supply would soon be depleted, so he was stopping the visits in the bud.

Retaliating, the Indians had decided to complain about Johnson to drive him out of the country, and this was what started the long series of hunts which terminated in his death.()

In any case, it appeared that the Aboriginal neighbours in question had reason to lodge a complaint with the RCMP about Albert Johnson. Even though they did not know the name of the man who had pointed the gun at them, Constable Millen strongly suspected from their description that it was the same person he had interviewed the previous summer: the man who had given his name as Albert Johnson.

Despite the severe winter travelling conditions and knowing little about the offender, Constable King and Special Constable Bernard did not anticipate that the assignment would be extraordinary in any way. They would simply make their way by dog team to Johnsons cabin, order him to leave other peoples lines alone and remind him to apply for his own trapping licence. Both constables were experienced with travel during the Arctic winter, and were confident that they could complete the 220-kilometre round trip in time to join their friends and colleagues at a New Years Eve party.

At that latitude (68 degrees north), only a few days after the longest night of the year, twilight lingers for a few hours around noon before giving way again to the dark of night. With temperatures hovering between -30C and -50C, the two police officers were grateful to spend their first night in the small community of Fort McPherson, approximately 70 kilometres west of their detachment. The next night, December 27, they were not so fortunate; they had to camp out in the snow and frigid cold near the mouth of the Rat River, their only consolation being that they did not have much farther left to travel.

Monday, December 28, 1931

King and Bernard arrived at the newcomers homestead around mid-morning and were heartened to see smoke billowing from the chimney of the spartan log cabin and the occupants handmade willow-frame caribou-hide snowshoes propped up against an exterior wall. Albert Johnson was obviously at home, so the officers had every reason to believe their dealings with him would be wrapped up quickly.

King knocked on the door with his heavily mittened hand. Much to his surprise, there was no answer. He called out to Johnson, identifying himself as a police officer. Still there was no answer. He called out again, adding that he only wanted to speak to him. Still there was no response. After waiting an hour in the bitter cold, the two constables left, knowing it was pointless to remain any longer. They also knew that this was no longer a routine investigation. Johnson had broken a long-held code of the North by not opening his door to someone who had asked to be let in. Any thoughts that Bernard and King had been entertaining about attending a New Years Eve celebration were blown away as effectively as if by the howling Arctic wind. Instead, they needed to go to Aklavik, roughly 80 kilometres away, where they would ask their commanding officer, Inspector Eames, to issue a search warrant.

Wednesday, December 30, 1931

Inspector Eames immediately agreed that the situation with Johnson needed to be taken very seriously. He not only issued the warrant as requested, but had Special Constable Lazarus Sittichinli, Constable Robert McDowell and an additional team of dogs accompany King and Bernard on their return visit.

Thursday, December 31, 1931

By the last day of the year, the cold had intensified and the wind had picked up, creating a temperature that was the equivalent of -67C. These were obviously extremely dangerous conditions. If hell were cold, surely it would have borne a close resemblance to these bleak and almost unbearable circumstances.

After a 28-hour trip, the four-man posse arrived at Johnsons cabin. It was just after 10:30 a.m. The Arctic dawn was breaking and, as on the previous visit, there was every indication that Johnson was in his cabin. Constable King knocked on the door and called out, identifying himself as a police officer and asking Johnson to open the door. This time the officers presence was acknowledged immediatelywith the crack of gunfire. King crumpled to the snow, the bullet lodged in his chest. McDowell opened fire. Even if he could not manage a clear shot at Johnson, he could at least divert the mans attention from King, who had obviously been seriously wounded. A vicious gunfight ensued, creating the necessary but potentially deadly diversion. While bullets whizzed everywhere around McDowell, King dragged himself, agonizingly slowly, out of the line of fire.

The three uninjured Mounties strapped their colleague to a sled. King was bleeding profusely, and his companions knew he would soon die if they did not get proper medical attention for him as soon as possible. Pushing the dog teams as fast as they dared, the men raced the 129 kilometres to the Aklavik hospital in a record-breaking 20 hours. One of the dogs collapsed and died from exhaustion along the route, but the mens efforts paid off: King was still alive.