1

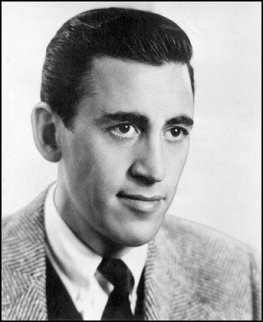

F our years ago, I wrote to the novelist J. D. Salinger, telling him that I proposed to write a study of his life and work. Would he be prepared to answer a few questions? I could either visit him at his home in Cornish, New Hampshire, or I could put my really very elementary queries in the mailwhich did he prefer? I pointed out to him that the few sketchy facts about his life that had been published were sometimes contradictory and that perhaps the time had come for him to set the record straight. I assured him that I was a serious critic and biographer, not at all to be confused with the fans and magazine reporters who had been plaguing him for thirty years. I think I even gave him a couple of dates he could choose from for my visit.

All this was, of course, entirely disingenuous. I knew very well that Salinger had been approached in this manner maybe a hundred times before, with no success. The idea of his record being straightened would, I was aware, be thoroughly repugnant to him. He didnt want there to be a record, andso far as I could tellhe was passionate in his contempt for the whole business of literary biography. He was contemptuous too of all book publishers (so much so that for two decades hed refused to let any of them see his work). When, in my letter, I vouchsafed that my project had been commissioned by Random House, I knew it would be instantly clear to him that I was working for the enemy.

I had not, then, expected a response to my approach. On the contrary, I had written just the sort of letter that Salingeras I imagined himwould heartily despise. At this stage, not getting a reply was the essential prologue to my plot. I had it in mind to attempt not a conventional biographythat would have been impossiblebut a kind of QuestforCorvo, with Salinger as quarry. According to my outline, the rebuffs I experienced would be as much part of the action as the triumphsindeed, it would not matter much if there were no triumphs. The ideaor one of the ideaswas to see what would happen if orthodox biographical procedures were to be applied to a subject who actively set himself to resist, and even to forestall, them.

For instance, it was saidon the recordthat Salinger had worked as a meat packer in Poland during the 1930s. Would it not make a readable adventure if some zealous biographer figure was to be seen trudging around the markets of Bydgoszcz making inquiries about a sulky-looking young American who had worked there for a week or so some fifty years before? Although this particular sortie was not actually on my agenda, the book I had in mind would, I conjectured, be full of such delights. It would be a biography, yes, but it would also be a semispoof in which the biographer would play a leading, sometimes comic, role.

And Salinger seemed to be the perfect subject. He was, in any real-life sense, invisible, as good as dead, and yet for many he still held an active mythic force. He was famous for not wanting to be famous. He claimed to loathe any sort of public scrutiny and yet he had made it his practice to scatter just a few misleading clues. It seemed to me that his books had one essential element in common: Their author was anxious, some would say overanxious, to be loved. And very nearly from the start, he had been lovedperhaps more wholeheartedly than any other American writer since the war. TheCatcherintheRye exercises a unique seductive powernot just for new young readers who discover it, but also for the million or so original admirers like me who still view Holden Caulfield with a fondness that is weirdly personal, almost possessive.

To state my own credentials: I remember that for many months after reading TheCatcher at the age of seventeen, I went around being Holden Caulfield. I carried his book everywhere with me as a kind of talisman. It seemed to me funnier, more touching, and more right about the way things were than anything else Id ever read. I would persuade prospective friends, especially girls, to read it as a test: If they didnt like it, didnt get it, they were out. But if they did, then somehow a foundation seemed to have been laid: Here was someone I could really talk to. For ages I thought I had discovered TheCatcherintheRye: I had come across it in a secondhand bookshop in Darlington, County Durham, and had bought it on the strength of its first sentence:

If you really want to hear about it, the first thing youll probably want to know is where I was born, and what my lousy childhood was like, and how my parents were occupied and all before they had me, and all that David Copperfield kind of crap, but I dont feel like going into it, if you want to know the truth.

What more audacious opening to a novel could be imaginedat any rate, by one whose own fiction at that time was darkly allegorical/archaic and, in its speech, almost euphuistically remote from the dialect of his northern English tribe? And of course the Catchers colloquial balancing act is not just something boldly headlined on page one: It is wonderfully sustained from first to last. And so too, it seemed to me, was everything else in the book: its humor, its pathos, and, above all, its wisdom, the certainty of its world view. Holden Caulfield knew the difference between the phony and the true. As I did. TheCatcher was the book that taught me what I ought already to have known: that literature can speak for you, not just to you. It seemed to me my book.

It was something of a setback when I eventually found out that I was perhaps the millionth adolescent to have felt this way, but I was by then safely engrossed by Beowulf and the Aeneid, Book III, a student of English literature at Oxford. Holden would say that this was where I started to go wrong, started along the path that would eventually lead me to the sort of literary folly I now had in mind, but I didnt know this at the time. My book had turned into everybodys book: Everybody had seen in it a message aimed at him.

In gratitude for this sensation of having been specially confided in, J. D. Salingers readers have granted him much fame and money and, if he has not altogether turned these down, he has been consistently churlish in accepting them. Now he wont even let us see what he is working on. Is he sulking? If so, where did we all go wrong? By studying English lit.? Or is he teasing ustesting our fidelity and, in the process, making sure that we wont ever totally abandon him? These were the sorts of question my whimsical biographer would play around with.

Of course, every biographer has a bit of the low tec in him, and minehaving made his first movenow looked forward to getting on the case. I was already thinking of him as somehow separate from me: a convenience or a necessity? Anyway, I got him started by firing off about two dozen form letters to all the Salingers listed in the Manhattan telephone directory. Where did the Salingers come from, I asked, and did any of these Salingers happen to know the novelist J.D.? I was hoping to tap the well-known American hunger for genealogy and, sure enough, the replies came storming back. But they were neither entertaining nor informative. Nobody knew anything of J.D. except that he had turned into a hermit, and several had never heard of him at all.

On the other hand, many of them did claim a connection with Pierre Salinger, John F. Kennedys press secretary, and it emerged from what they said that there were in fact two sorts of Salinger. One sort hailed from Alsace-Lorraine; the other from Eastern Europe, perhaps Poland. The French branch was far more numerous and self-knowing than the Polish, and J.D.it was soon evidentbelonged to the more shadowy East European line. Had he ever himself tried to find out about his origins and, failing to do so, become charmed by some sense of his own elusiveness?