About the Book

When Polly Evans read a survey claiming that the last bastion of masculinity, the real Kiwi bloke, was about to breathe his last, she was seized by a sense of foreboding. Abandoning the London winter she took off on a motorbike for the windswept beaches and golden plains of New Zealand, hoping to root out some examples of this endangered species for posterity. But her challenges didnt stop at the men.

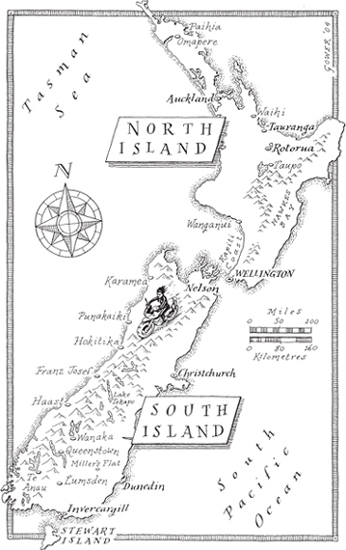

Just weeks after passing her bike test, Polly rode from Aucklands glitzy Viaduct Basin to the vineyards of Hawkes Bay and on to the Southern Alps. She found wild kiwis in the dead of night, kayaked among dolphins at dawn, and spent an evening on a remote hillside with a sheep-shearing gang. As she travelled, Polly reflected on the Maori warriors who carved their enemies bones into cutlery, the pioneer family who lived in a tree, and the flamboyant gold miners who lit their pipes with five-pound notes, and wondered how their descendents could have become pathologically obsessed with helpfulness and Coronation Street.

The author of the highly acclaimed Its Not About the Tapas reaches some unexpected conclusions about the new New Zealand man and finds that evolution has taken an unlikely twist.

Contents

For my godson, Alistair and my nephew, Zac

Acknowledgements

The people of New Zealand really are immensely helpful almost fanatically so, in fact so I should probably start off by saying a big thank you to all four million of them for their gestures of friendliness that made my journey so memorable.

Special thanks to Ian and John Fitzwater at Adventure New Zealand Motorcycle Tours & Rentals (www.gotournz.com) for providing me with a fantastic bike, and for their faultless recommendations of the best roads, the most comfortable hotels and the most outstanding restaurants.

Thanks to Gordi Meyer who looked after me in Auckland, took me for a very exciting ride in a police car, and bravely gave me the telephone numbers of his friends around the country.

Sir Henry Every very kindly spent many hours tracking down members of the New Zealand branch of his family and providing me with contacts, so many thanks to him, and to his relatives Chris and Adrienne Rodgers and Richard and Phyllis Bruce for their hospitality.

For their company, comfortable beds and insights into strange Kiwi ways, thanks also to Mary, Bill and Tiggy Farrell, Eileen Birch, Morris and Fay Wharekawa, Lawrie and Carol Chandler, Pete and Skiff, the Hansen family, Frano Barker and Michael Keith, Lee Matson, Dave and the shearers, Frances and Brian Ward, Brendon, Veronica and Sandy Park, Kyle and Marion Mewburn, and to Sheena Ashford-Tait and Duncan Ashford for the night in the camper van.

Andrea Brunetti at Dainese and Dan at Chiswick Honda kitted me out in a fantastic set of black leathers that, dare I say it, were really rather attractive. Well, I thought so anyway.

And to Jane Gregory and Broo Doherty and all at Gregory and Company, and to Francesca Liversidge and everyone at Transworld, thanks as ever for their friendship, enthusiasm and professional expertise.

Rocking the Cradle

SO, SIN, MY neurologist friend, asked brightly, are you going to wear one of those motorcycle helmets that covers the back of your head up to your fourth cervical vertebra, so that if you crash youre left tetraplegic, or are you going to get one of those higher-cut ones so that youre killed outright instead?

My stomach lurched. I was deeply afraid.

It had all started a few months earlier, when Id read a survey that claimed the ordinary Kiwi bloke was about to turn up the toes of his gumboots. He was, apparently, hanging up his sheep shears and moving to the city. A new masculinity was rearing its pretty, hair-gelled head. Men were waxing their backs. In ten years, said the survey, the traditional, hirsute New Zealand man would be dead.

The early New Zealanders had been virile and vigorous. The Maori were fearless warriors. Then the Europeans had arrived after arduous journeys across thousands of miles of treacherous ocean. The life that awaited them was hard.

New Zealand men grew up to be strong. They slaughtered whales, panned for gold and felled timber. They learned to play rugby. Fearlessly, they drank home-brewed beer. Then something went wrong. The environment changed; the species had to mutate. Volcanic eruptions? Tectonic shifts? An overboiling of the primordial soup? No. It was none of these things. It had more to do with washing machines from Japan.

With the arrival of aeroplanes and domestic appliances, the fences came unstuck for the traditional New Zealand man. What did it matter if he could mend a tractor using three bits of old wire and a pot of distilled sheep dung when spare parts were lined up at the local Kawasaki store? The real Kiwi bloke was fast becoming redundant.

The curious thing was that nobody seemed to be making much of a fuss about his demise. When other creatures have faced extinction when the tiger threatened to roar no more, or the red-legged frog looked fit to croak the conservationists beat their chests like gorillas whose trees just got the chop. But when the Kiwi bloke, an almost-human species, began to shuffle off to the big brewery in the sky, nobody seemed much bothered. One or two insensitive souls even breathed a quiet sigh of relief.

There was nothing else for it. Somebody was going to have to travel to the other side of the globe, to delve deep into the New Zealand countryside, to sniff around on sheep farms and poke about in rural pubs and ask the question: is the Kiwi bloke really about to breathe his last?

It was cold and raining at home in London; in New Zealand it was summer, the perfect time to hunt out a shy species on the verge of extinction from its spectacular alpine hideaways and wave-swept beachside lairs. It looked as though that somebody might have to be me.

I thought Id tour New Zealand on a motorbike. Kiwi men were known to be fond of machinery; these were the guys who were meant to be able to strip down the engine of their truck on a Sunday afternoon and have it working again by Monday. If I rode a motorbike, I thought, and, better still, if I shoehorned myself into the tightest set of black motorcycling leathers I could find, I should stand a greater chance of luring these timid men from their hunting grounds and watering holes. If I was really lucky, I might even persuade one or two of them to speak.

I enrolled in motorcycling classes. Working on the basis that there are fewer maniacal cars out to kill a learner motorcyclist in the countryside than in the town, I decided to take lessons in the depths of rural Derbyshire.

I shared my first days training with two sixteen-year-old boys who had just been given their first mopeds. We learned that cool kids ride safely. The two boys set off round the traffic cones on their gloriously gearless scooters. I got less than a metre before the 125cc training bike coughed, gave a little shudder, and stalled. I tried again.

You gotta treat the clutch gently, Oz, the instructor, admonished me. He was a big, grizzled man with stubbly grey facial hair and well-worn leathers. Handle it like, well now he looked embarrassed we always say like youd handle a woman.

He shuffled and grinned. I raised an eyebrow. Not only was I expected to ride this piece of killer machinery, now I was meant to build a meaningful relationship with it as well. I tried again. The bike hiccuped, coughed, and stopped.

Next page