About the Book

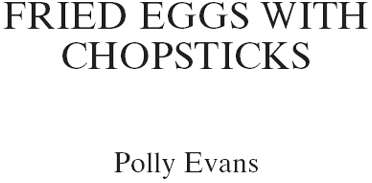

When she learnt that the Chinese had built enough new roads to circle the equator sixteen times, Polly Evans decided to go and witness for herself the way this vast nation was hurtling into the technological age. But on arriving in China she found the building work wasnt quite finished.

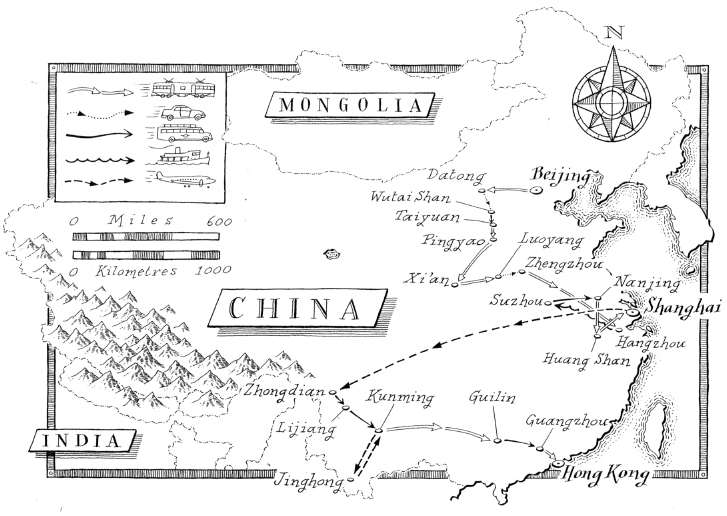

Squeezed up against Buddhist monks, squawking chickens and on one happy occasion a soldier named Hero, Polly clattered along pot-holed tracks from the snow-capped mountains of Shangri-La to the bear-infested jungles of the south. She braved encounters with a sadistic masseur, a ridiculously flexible kung-fu teacher, and a terrified child who screamed at the sight of her.

In quieter moments, Polly contemplated Chinas long and colourful history the seven-foot-tall eunuch commander who sailed the globe in search of treasure; the empress that chopped off her rivals hands and feet and boiled them to make soup and pondered the bizarre traits of the modern mandarins. And, as she travelled, she attempted to solve the ultimate gastronomic conundrum: just how does one eat a soft-fried egg with chopsticks?

Contents

For Sophie and Lee, wishing you every happiness

Acknowledgements

China is not an easy place for a linguistically impaired foreigner to travel around, and my trip would have been all the more challenging without the help of both good friends and total strangers.

Without the assistance of Guy Rubin and Nancy Kim, theres a good chance I wouldnt have got beyond Datong. Their knowledge of China, their contacts and, on one dire occasion, their impromptu dial-a-translation service were invaluable. A huge thank you to both of them. (For more comfortable tours of China, check out Guy and Nancys Imperial Tours website at www.imperialtours.net).

Thanks also to Yeshi Gyetsa and his team at Khampa Caravan (www.khampacaravan.com) who provided a fantastic trek into eastern Tibet.

Thanks to Annie, my guide in Yangshuo, and her mother for that amazing lunch, and to Pascoe Trott and Clive Saffery for company and alcoholic refuge.

The Sheraton Xian, the Grand Hyatt in Shanghai, and the Gyalthang Dzong Hotel in Zhongdian kindly laid on much needed interludes of five-star luxury.

Id also like to thank all those random Chinese strangers who, with unfathamable generosity and kindness, stepped out of the mire of Chinese bureaucracy and pointed me in the right direction, escorted me onto the right bus, fixed my ticket conundrums, and beamed goodwill and friendship in my direction. It made all the difference.

And thanks as ever to Francesca Liversidge, Helen Wilson and everyone at Transworld, and to Jane Gregory, Anna Valdinger, Claire Morris and everyone at Gregory and Company for their wisdom, humour and friendship.

The Chairman is Dead

I GAZED WITH ghoulish fascination at the withered, waxen corpse. The infamous domed forehead and rounded cheeks looked weary and wrinkled, a far cry from the jubilant, plump jowls of the propaganda posters. The embalmed cadaver of Chairman Mao lay swaddled in military uniform, his hands crossed over his chest. An orange lamp beamed through the semi-darkness onto his shrivelled, death-stiffened skin. His face glowed like a ghastly, candlelit pumpkin.

A hushed awe filled this inner chamber of the mausoleum. Nobody spoke above a whisper. The room quivered with palpable excitement. My heart was beating faster than usual; a perverse thrill tickled my skin. I felt a morbid compulsion to stop and stare at the macabre spectacle, at the mortal remains of this man who had, to such catastrophic effect, held absolute power over the most populous nation on earth. A few decades ago, a single suggestion from that formaldehyde-plumped mouth could have spelt the slaughter of a man; the disastrous economic strategies that evolved in that glowing amber head had dealt a tortured death to tens of millions. Yet beneath that taut, unyielding skin had also breathed a man who had, against incredible odds, inflamed such passion and loyalty in his people that a vast and diverse country had united and, with almost no material resources, had overthrown the foreign super-powers that threatened it.

The embalming of Maos corpse had been an anxious affair according to his personal physician Li Zhisui, who recorded the procedure in his book The Private Life of Chairman Mao. The problem was that neither Li, nor anyone else in China, had attempted to preserve human flesh before. Li himself had visited Stalins and Lenins remains some years previously and had noted that the bodies were shrunken. He had been told that Lenins nose and ears had rotted and had been rebuilt in wax and that Stalins moustache had fallen off. The medical team played for time by pumping Maos corpse full of formaldehyde.

We injected a total of twenty-two litres, Li wrote. The results were shocking. Maos face was bloated, as round as a ball, and his neck was now the width of his head. His skin was shiny, and the formaldehyde oozed from his pores like perspiration. His ears were swollen too, sticking out from his head at right angles. The corpse was grotesque.

The terrified medics who could have been executed for desecrating the semi-divine cadaver tried to massage the liquid out from the face and down into the body where the bloating could be covered with clothing. One of them pressed too hard and broke a piece of skin off Maos cheek. In the end, they managed to restore his face to something approaching normal proportions, but then the Chairmans clothes wouldnt fit on his body and they had to slit the back of his jacket and trousers in order to button them up.

Before carrying out the permanent preservation of the body, Li sent two investigators to Hanoi to find out how Ho Chi Minhs body had been treated. When they arrived, however, the Vietnamese officials refused to divulge their secrets and wouldnt allow them to see the corpse though someone revealed confidentially that it hadnt been a great success. Hos nose had already decomposed and his beard had fallen off.

In the end, Li worked out a method whereby he removed Maos internal organs and filled the cavity with cotton soaked in formaldehyde, while another group worked day and night building a pseudo-corpse out of wax just in case it all went wrong and they found themselves in need of a fake.

I wondered whether the body that lay before me was, in fact, the real cadaver or the waxen substitute. It was nearly thirty years since Maos death; the pickling process had clearly been experimental at best. It seemed entirely possible that the real corpse could have long since rotted away and been quietly replaced with a skilfully crafted effigy.

But I wasnt allowed to linger. A dark-suited official insisted that the line of pilgrims kept moving. Silently, I filed with the coachloads of fellow tourists out of the dim mausoleum of the past and into the bright white light of contemporary Tiananmen Square.

Follow me! Quick-a-ly! A Chinese man dressed in a slightly soiled tracksuit top, baggy black jogging pants and scuffed pumps hollered at a white-haired Western tourist who stood in the queue that snaked around the cubic, concrete mausoleum. Amid the bedlam of loudly jabbering, camera-wielding day-trippers, the tourist nervously clutched his bag to his hip. The Chinese clasped the shoulder of the tourists jacket and tried to pull him out of the queue. The tourist looked terrified.

He neednt have worried; I had been through the same charade just a few minutes earlier. Bags were forbidden in the mausoleum and the left-luggage office was on the other side of one of the busy roads that flanked the square. Seeing my bag, the man had grabbed me.

Next page