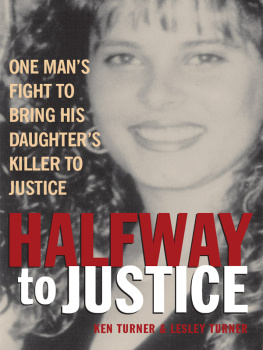

M y daughter Julie was a funny mixture of introvert and extrovert. She was shy as a child but could be feisty in arguments when she thought she was in the right, and she didnt let anyone walk over her. She was hopelessly messy at home, dropping clothes where she took them off and leaving teacups lying around but she never stepped out of the house without being perfectly groomed. She wouldnt want to be the centre of attention in a crowd, but around those she loved she never stopped talking, telling us anything and everything that was going through her head.

Julie was beautiful from the day she was born, with a slight oriental look from her Dads side of the family, and dark colouring that let her get away with wearing the most dazzling bright colours. As a little girl she loved dressing her Sindy dolls for hours on end, and in her teens it was herself she dressed up. Shed wear ridiculously high heels, super-tight skirts and trousers showing off her perfect, slim figure, and eccentric shirts and jackets all layered on top of each other. Her hairstyle changed from month to month, but whether it was Boy George dreadlocks wrapped in rags, or a bright turquoise fringe, nothing fazed me. No matter how flamboyant an outfit she put together, she always looked stunning.

Julie had a dry (some would say warped!) sense of humour and an infectious giggle that bubbled out at inappropriate moments. She liked dancing, gymnastics and doing peoples hair for them. She was a fantastic mother to her little boy Kevin, and fiercely loyal to her family and her close circle of good friends.

She was full of life and always fun to be with. She was my little girl and I adored her.

I n Middlesborough in the late 1960s it was the custom for mothers who had had one straightforward birth in hospital to deliver their babies at home after that, which is a daunting prospect for anyone, even for someone like me who prides herself on being a down-to-earth Yorkshirewoman. So many different fears and thoughts are racing through your head as your due date draws near. What if something goes wrong? What if the baby comes early, or gets stuck? When a newborn babys life could be at stake it is very comforting to know you have all the technology and expertise of a well-equipped hospital at your disposal, rather than one midwife, a panicking husband and a pan full of boiling water. That option, however, was not on offer to us.

My mind was buzzing with fears of imagined disasters and imminent emergency ambulance rides as the pain started to build up. My mam took my two-year-old son Gary off for a walk in his pushchair to keep him out of the way. The midwife had popped in when the contractions started in the morning but then disappeared off, breezily saying she would be back at lunchtime, leaving my husband, Charlie, plenty of time to panic as my moans increased in frequency and he started to imagine having to perform the delivery himself. No doubt the midwife had plenty of other patients to tend to; for her it was just another days work, even if it meant a lot more to us.

By eleven oclock I had to go upstairs and lie down, hauling myself up on the banister, memories of just how painful the whole childbirth business is coming rushing back with every spasm. How is it that we women manage to forget all that agony almost the moment it is over? I could hear Charlie making frantic phone calls downstairs as I concentrated on the pain upstairs, lying on the bed, wanting it all to be over but not wanting the baby to come before the midwife got back.

The girl answering the phone at the doctors surgery must have asked Charlie if I was starting to push.

Are yer starting to push? he shouted up.

No, I yelled back.

Well, if the babys born, the girl told him, just wrap it in a blanket, wipe its eyes and put it on the side. Dont try to cut the cord.

This is good, I heard him grumbling as he put the phone down. I pay me National Health stamps and theres nobody here when you need them!

The doctor sauntered in at about twelve to take a look and immediately saw that I was ready to deliver whether the midwife was there or not.

Id better go and wash my hands, he said, but just then the midwife bustled back in and he decided to go downstairs to keep Charlie company instead.

Ill wait around in case you need stitches afterwards, he said.

I dare say the two men were brewing up for a cup of tea as we women got down to work in the bedroom.

The birth itself was blissful and peaceful. Shes arrived like an angel! exclaimed the midwife, as Julie emerged into the world with her arms folded beatifically across her chest. That was the first I knew I had a girl, because of course we didnt have scans that could tell you in those days.

I hauled myself up on my elbows to catch a glimpse of my new daughter.

My goodness, the midwife marvelled, Ive never seen a baby with so much hair.

She was right: a thick mop of blue-black hair stretched down the back of the new babys neck, a clear sign of her Chinese ancestry.

Shell probably lose it all over the next few weeks, she said, before she grows it back in again.

But she didnt lose it. Julies hair just grew thicker and darker and more lustrous with every passing week. The midwife, who became a regular visitor and friend over the following years, had to cut it after a month to let some air get to her little neck, pushing a hair slide into the side to keep it out of her eyes at an age when most babies have no more than a few tufts of fluff for a mother to brush lovingly.

I needed a few stitches after the delivery so Charlie was sent back to the kitchen to boil some needles for the doctor in a pan of water that hed been preparing to cook some vegetables in for our lunch.

It was a Wednesday, 22 February 1967. Wednesdays child is full of woe, as the saying goes, which is what we used to say to Julie later whenever she was moaning at us about something or other. We could never have imagined how prophetic that silly little saying would turn out to be as we went about building our family life just like everyone else. None of us can ever know what lies in store for us, which is just as well.

As I lay in bed that afternoon, holding her in my arms for the first time, I never for a second would have believed that this tiny, helpless baby would die before I did, or that she would die in one of the most terrible ways possible. Such a thought would have been simply unbearable. At that moment my maternal instincts were to protect this vulnerable little bundle from everything life would throw at her but it was an illusion because no mother can ever really hope to do that.

When your children are small you keep an eye on them most of the time, although even then accidents can still happen or terrible luck can befall them. But once they have grown up and left the nest you can do nothing but have faith that they will be all right, that they will not take too many risks or make too many bad judgements. And then all you can do is be there for them if things go wrong. But no matter how grown up and capable they become, I dont think a mother ever loses that initial instinct to guard her babies and fight for their safety and their rights against the rest of the world. Thankfully, not many have to do it in such horrific circumstances as I would have to.

I first spotted Charlie Ming in 1962, sitting with a group of other men in a Chinese restaurant in Middlesborough called The Red Sun. I was just sixteen but had been out of school for a year and was more than ready for a bit of life. It was an exciting place for a young girl to be because there werent many Chinese restaurants around in those days, not like today when there are fast-food outlets of every nationality on every street corner. In fact most people didnt eat out much at all; we didnt have anything like the amount of disposable money they have today.