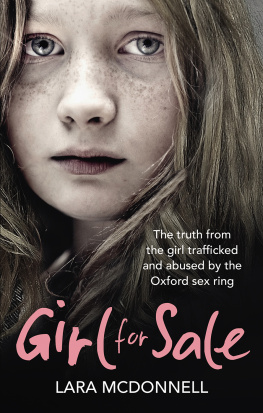

To Lara, Noah and Olivia,

the best is yet to be.

This book is also dedicated to the memory of our dear friend Mary who shared much of the desperation of the times described here with us, but who died before she could see us survive and emerge the other side.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

We are sitting at the back of court 12 in the Old Bailey underneath the public gallery so we cant be seen. Four of the six victims are here, with either a family member or social worker or similar. Each of us has a police officer sitting with us, which makes us feel cared for and protected. We have come to court for the sentencing of the Oxford gang who groomed, trafficked and abused six girls for over eight years. One of those girls is sitting beside me, bolt upright, a terrified look in her eyes. She is my daughter, Lara. She is now nearly twenty-one, but was just twelve years old when she fell into their clutches. She is shaking like a leaf but determined to see this through. I am surprised to realize that I have never before met the three other victims who are here today. They are not girls Lara used to hang around with, although one of the two girls who have chosen not to be here was.

Stuck at the back of the court, its really hard to hear the judge. Did he say, Life? I turn to the police officer next to me and see she is grinning and giving the thumbs-up to a colleague. And then it keeps coming: Life... Life... Life... Life... Life...

The court is quietly buzzing now. A couple of the journalists, including a familiar face, Naresh Puri from the BBC, leave the courtroom, presumably wanting to be the first to broadcast the news of the sentences to the outside world. The rest of the journalists are scribbling or texting furiously. The police are exchanging triumphant glances and discreet air punches. The jury, too, most of whom have returned for the sentencing, are looking jubilant. Sadly, from our position, all we can really see are the backs of the heads of the defence barristers, but one of the prosecution barristers is chuckling and keeps tipping his wig over his eyes.

Not all of the gang are in court for the sentencing, and its hard to see them anyway because we are below the glass-fronted dock, but I need to try and get one good look at the men who blighted our lives for so long, so I stand up and stare into the dock. One of them is yawning, another smirking; the rest are staring into space. They look rather pathetic and insignificant with their masks of indifference. I want to look at them and feel full of hate and rage, but I dont. Contempt is about all I can muster.

Then the judge starts to catalogue some of the offences. The details are so awful they cant be reported in the media. I thought I pretty much knew everything that had happened, but I havent been present for the entire trial, and some of the information being revealed now by the judge in his quiet, moderate, unemotional voice is beyond belief. Indescribable acts of sadistic depravity inflicted on children as young as eleven. Gradually my feelings of triumph and revenge evaporate, to be replaced by utter desolation and a grief far stronger than I have ever felt before. The distillation of eight years of abuse, suffering, pain, worry, shock and anger into a few minutes of judicial summing-up is so powerful, so potent that its overwhelming. Suddenly I have a sense of the true awfulness of what happened to Lara and the other girls in a way I have never felt before. Stripped of the extraneous padding of our everyday life, which of course went on throughout the episodes of abuse, the sum total of the crimes themselves is too intense to bear. Its hard to breathe, and even though I feel a fool for crying when we have at last succeeded, the tears wont stop. Everywhere I look around the court the press benches, the police, the jury, everywhere except the dock I see people with tears streaming down their faces.

The judge praises the girls bravery in giving evidence, thanks the police, and then, suddenly, its all over and Lara and I leave the courtroom, ushered out in a protective huddle of police officers and witness support volunteers. Several of the journalists and reporters we have got to know over the last few months come up to us. There are smiles and handshakes, even kisses. Congratulations; Fantastic result; You must be so pleased; How does it feel?; Can you give us a reaction?

Lara doesnt want to speak to anyone, but I agree to talk to a few reporters who by now feel like old friends. We have shared a lot with them, had some of them in our home to pre-record carefully anonymized interviews for radio, television and newspapers. The journalists we have chosen to give interviews to have, by and large, shown us great respect and empathy, and treated Laras story with enormous sensitivity. Of course they want a final comment from us on this tumultuous day.

The problem is, I dont know how I feel... I do know that justice has been served and that life sentences show the world just how serious these crimes are, and I hope it will mark a turning point in how the courts treat child exploitation in the future. I hope, too, that it will demonstrate to Lara the true severity of what happened to her. But I cant dredge up any sound bites; I cant even articulate how I feel about the men. I feel absolutely nothing except overwhelming grief. Hollow, grey and bitter.

BBC News has booked a room in a pub over the road from the Old Bailey to record a quick interview. Lara and my brother Michael go over to wait for me, along with some of the police. We dodge the cameras on the pavement recording interviews with the Crown Prosecution Service and police. I mutter a few meaningless words to the BBCs social affairs correspondent, Alison Holt, while the cameraman carefully films just the back of my head to ensure my anonymity, and then I go to find Michael and Lara in the upstairs bar. There is a party going on.

It feels like being with a group of colleagues out in the pub on a Friday night to celebrate the end of a successful week at work. Most of these Thames Valley police officers I have never met before, but they have all worked on the case as part of Operation Bullfinch. Their sense of achievement, of a job well done, is very clear, as is the amount of personal commitment most of them have given.

After a few minutes a group of the Old Baileys witness support volunteers who looked after us and the other witnesses in court come into the bar. They are warm and delightful women, mostly in their late sixties and seventies, and look as though they would be more at home at a coffee morning than supporting witnesses in a child exploitation and prostitution trial. They have shown great insight, understanding and compassion throughout. Now they, too, want to mark the end of a case, one that they say, even by Old Bailey standards, was complex and harrowing in the extreme. They dont join us, but we smile and wave across the bar, sharing a mutual sense of satisfaction and relief.

And then we are off, crawling through Londons rush-hour traffic, back to Wales, driven by two personal protection police officers who have chauffeured us back and forth many times over the past four months. We talk and joke with the police about the traffic, the weather, other drivers on the road, anything but what we have all just witnessed. Emotionally drained, there are no words left to talk about that. No one even wants to try. We head back to the sanctuary we found when we fled Oxford and the gang three years earlier, with their threats to cut off our faces, slit our throats and behead us ringing in our ears.