Five bells. Five bells coldly ringing out.

Five bells.

Foreword

In his memoir of living in Verona, English novelist Tim Parks suggests the Italian love of la dolce vita is not quite what it seems. As he was watching television footage of one of Italys naval ships heading for Beirut on a UN mission, he recalls, the camera panned onto a young sailor calling back to shore. Was he shouting farewells to a girlfriend, or boyfriend, or uttering some howl of defiance? No, as the camera drew closer to his red face it became clear that he was tearfully mouthing the word Mamma. Thus Parks makes his case. The Italians casual cheer is only a front. They are essentially homebodies, disturbed by cuisine from another region, let alone any more drastic changes.

A similar case can be made for Sydney. From the outside it seems like the brashest and most superficial of cities, almost a kind of unplanned holiday resort. But perhaps you need to have grown up here, as I did, to see that its fundamental temperament is melancholy. Everything else is a side effect, a symptom of darker emotional currents that run so deep they are almost tectonic. Sydney may look golden, but this is the sunniness of Mozart, whose bright notes, especially at their most joyful, seem to cast themselves out across a great abyss.

Just the other day I was walking up the hill from my apartment at dusk when I saw a small silver car with a parking ticket on its windscreen. The envelope looked strange. When I got closer I saw that someone had written on it in black texta: I just backed into your car, and now Im pretending to write a note. FUCK YOU! It wasnt hard to imagine the triple assault as the owner returned: horror at seeing the parking ticket, and the big dent from a four-wheel-drives tow-bar in the bonnet, then relief on finding the note that turned quickly into outrage. My God, if you could do that you could rape someone, a Melbourne friend said, horrified. But there was a part of me that felt some base response of familiarity, even of pride. This was my town. It was a place you took lightly at your peril, whose beauty has never been far from rage, and perhaps even the urge for destruction.

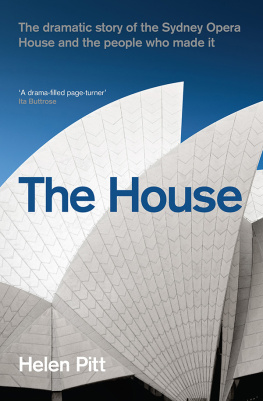

Like Los Angeles, with which it is sometimes unfavourably compared, Sydneys misty sunshine is never far from noir. And like Los Angeles, an Art Deco golden age cast its features its Bridge, its Luna Park, its mission-style mansions like Boomerang, its palms into a smile. It has been as ravaged by the car, as dazzled by its improbable location, as prone to boosterism and corruption as Los Angeles. Its air can look as luminous and insubstantial. But to Deco lightness, in Sydneys case, you have to add sandstone as a kind of base note, an ever-present reminder of its Georgian beginnings and more ancient past. To that mix, again, you have to add water, which penetrates the city with bright fingers, filters constantly through its foundations, and weighs down the air. While Los Angeles moments of darkness seem to come from a sense of dry ignition, an inkling that the citys desert winds, like the Santa Ana immortalised by Joan Didion, spark desperate acts, Sydneys seem more like the precipitation of something already moody and brooding, out of air that sweats. Similarly, Sydneys skies are so dense and changeable that it is hard to share Los Angeles shock that evil activities could hide themselves under its calm, relentless sun. Any madness here feels more chthonic, something deeply buried that wells up. While for Didion, the key image of that Pacific city is the paper in her typewriter curling in the heat, my childhood memories are of the dark layer of black pollution and mould soaked into the sandstone fronts of Sydneys grand buildings, and the green trails of water leaking from the cliffs and high walls of the Rocks. That, and the great posts of the ferry jetties that always seemed to be decomposing before ones eyes in the jellyfish-filled water, with their smell of brine and rot.

Yet for all the accusations of brainlessness made against them, both cities are where you will find the most feral, interesting thinkers. This was one of my first impulses, in taking on this project to try to come to grips with how people have thought and dreamed here, to confound the prejudice that this is a shallow place that generates more heat than light. With its love of eccentrics and poets, Sydney has a more paradoxical, more visionary, even more iconoclastic, intellectual history than that of any other Australian city. Yet at the same time, and this is part of its paradoxical nature, you would be hard-pressed to find elsewhere thinkers as palpably earth-bound. My thoughts turned to the writers Kenneth Slessor, Patrick White and Ruth Park, who took the citys grimy pulse from its stained footpaths and shabby terraces. I recalled First Fleet Lieutenant William Dawes, whose notebooks recording the Eora language began with strict grammars only to flare out into jottings about blowing out candles and touching hands.

Think in Sydney and you can be no cold metaphysician. The material constantly intrudes even as I write, a pulpy smell of iodine from the over-warm February harbour comes through the window and this freights every one of its books, paintings and conversations. Even a walk up the street is often literally up, as the city climbs to precipitous cliffs at its sea edge, in contrast to a metropolis like Manhattan where every rise and declivity has been razed. Yet this constant awareness of the material, which goes back to our Georgian past and its interest in the bodys humours like bile and phlegm, is quite different from shallow materialism. In fact, paying close attention to the citys tides and sunlight can even constitute an antidote to the citys pretensions to glamour; at the very least it gives our appetites an edge. The distinction is hard for outsiders to grasp.