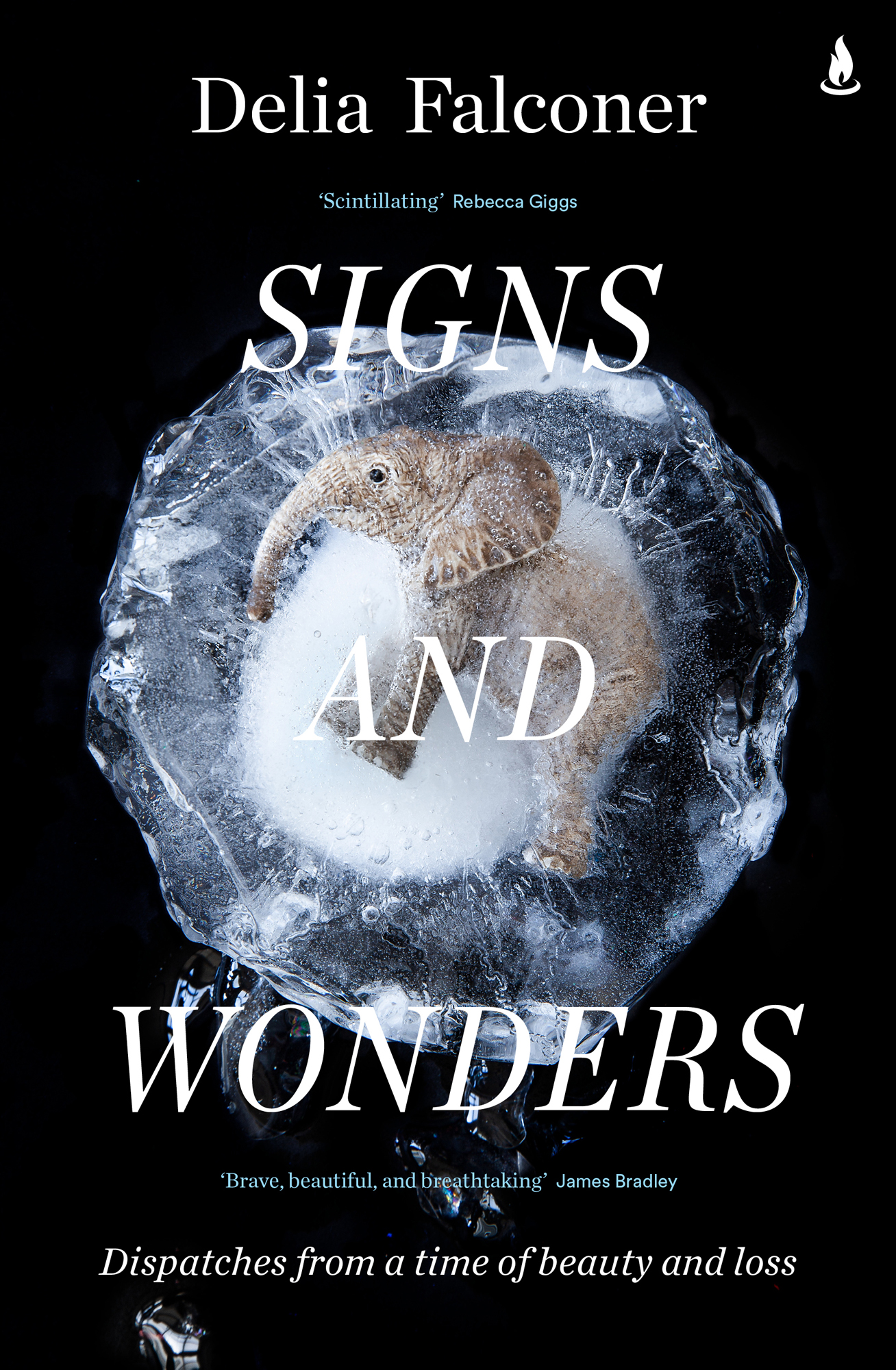

Delia Falconer - Signs and Wonders: Dispatches from a time of beauty and loss

Here you can read online Delia Falconer - Signs and Wonders: Dispatches from a time of beauty and loss full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2021, publisher: Simon & Schuster Australia, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Signs and Wonders: Dispatches from a time of beauty and loss

- Author:

- Publisher:Simon & Schuster Australia

- Genre:

- Year:2021

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

Signs and Wonders: Dispatches from a time of beauty and loss: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Signs and Wonders: Dispatches from a time of beauty and loss" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The celebrated, Walkley Award-winning author on how global warming is changing not only our climate but our culture. Beautifully observed, brilliantly argued and deeply felt, these essays show that our emotions, our art, our relationships with the generations around us all the delicate networks that make us who we are have already been transformed.

In Signs and Wonders, Falconer explores how it feels to live as a reader, a writer, a lover of nature and a mother of small children in an era of profound ecological change.

Building on Falconers two acclaimed essays, Signs and Wonders and the Walkley Award-winning The Opposite of Glamour, Signs and Wonders is a pioneering examination of how we are changing our culture, language and imaginations along with our climate. Is a mammoth emerging from the permafrost beautiful or terrifying? How is our imagination affected when something that used to be ordinary like a car windscreen smeared with insects becomes unimaginable? What can the disappearance of the paragraph from much contemporary writing tell us about whats happening in the modern mind?

Scientists write about a great acceleration in human impact on the natural world. Signs and Wonders shows that we are also in a period of profound cultural acceleration, which is just as dynamic, strange, extreme and, sometimes, beautiful. Ranging from an unnatural history of coal to the effect of a large fur seal turning up in the park below her apartment, this book is a searching and poetic examination of the ways we are thinking about how, and why, to live now.

Only the finest of writers can hope to convey the mercurial nature of the times we are living though: the sense of slippage; of terror and beauty. Falconer is such a writer. Signs and Wonders is an essential collection. Sophie Cunningham, author of City of Trees

Delia Falconer is one of the best writers working today, and in Signs and Wonders she demonstrates everything that makes her writing so necessary. Brave, beautiful, and breathtaking in its elegance and intelligence, it is, quite simply, a marvel. James Bradley

Scintillating. Delia Falconer is at the peak of her powers as a critic, and as an observer of the natural world. Signs and Wonders looks outward from Sydney, and from literature, to trace the contours of our environmental moment. Rebecca Giggs, author of Fathoms

Exquisite ... From reflections on feeding birds, analyses of literary trends, to Falconers Covid and fire diaries, the essays are complex, ambitious, rewarding ... Delia Falconers mesmerising Signs and Wonders helps us to process the disorienting complexity of living in this time of great beauty and loss. Jonica Newby, Australian Book Review

Delia Falconer: author's other books

Who wrote Signs and Wonders: Dispatches from a time of beauty and loss? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.