CARN EIGE

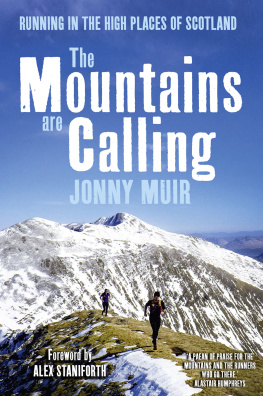

The world seemed about to end. Nature was wreaking her revenge. A shrieking storm laced with daggers of icy shrapnel. Ghastly drum beats of thunder as if mountains were cleaving and tumbling. Shadows were moving in, growing darker by the moment. A captive in a mist-obscured prison, my universe had shrunk to no more than five metres in any direction. The sky had succumbed. The valley had vanished. Life on Earth was no more. I was the only one left, a desperate stumbling soul.

An hour earlier, I had been sheltering in the sanctuary of the stone cairn on the 1,183-metre summit of remote Carn Eige, the highest point in the old Scottish county of Ross and Cromarty and the 12th tallest mountain in the UK. Now I was wandering aimlessly east across rock and ridge, willing the devilish furore to hoist me from this perilous perch and end the misery. I was lost, and with every step if such a thing were possible becoming ever more lost. The right way led to the west, first over Mam Sodhail, and then down a bealach which would return me to Glen Affric. If it still existed.

Instead, I was ghosting towards oblivion, time passing in a blur. It was five hours, maybe six, since I had left my bicycle on the midge-cursed shores of Loch Affric. They had been dreadful hours, the omens ill from the off. My last human contact had come with a thick-set Scot marshalling a quad bike along a path, which had been flooded by a swollen stream. I stood aside, watching the vehicle approach through the gloom and slanting rain. Hoisted on the rear of the quad bike was an adult stag, slain that day by a stalkers bullet, blood still dripping from its gaping mouth. Gazing into the beasts black eyes, I had shuddered as a wave of anxiety swept over me. It was little wonder nature sought revenge.

Quelling doubts and fears, up the mountain I had gone, in search of the pot of gold the summit. It didnt matter how, just get there. Sloshing through pools of green slime and brown sludge, fumbling across rolling scree and ankle-jarring rocks, staggering over grassy tussocks and wading through surging streams. Small steps, never pausing, eyes fixed on the ground. Heavy heart, heavy legs.

As I zigzagged up a thin track to the high ridge attaching Ciste Dhubh and Mam Sodhail, the wind lulled for a moment. During this peaceful calm the only sounds were the drip-drip-drip of raindrops on the hood of my waterproof and the distant pounding water of Allt Coire Leachavie. As I stepped on to the exposed ridge, the wind returned, a frantic, furious swirl, hurling icy pins that pricked exposed cheeks and forehead. From that moment till now, the storm had refused to leave. Relentless winds eddied, gyrated and twisted across Mam Sodhail and Carn Eige, at times forcing me to crawl on all fours, clinging to the mountains bare rock for dear life.

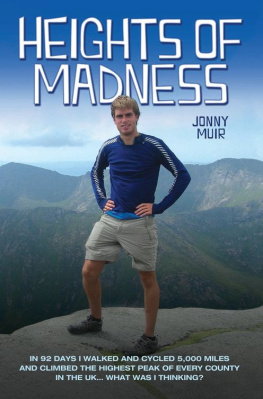

The concentration, the effort, the endurance: I felt I could bear it no longer. Before this interminable struggle, I had already tortured my hollow legs by pedalling 55 miles from Invergordon to Loch Affric. That was on top of the 4,200 miles I had cycled, from Cornwall to Shetland, and the 500 miles I had walked, all in the previous 90 days. The mountains, of course, had no sympathy. To them I was nothing but a 25-year-old scrap of skin and bone daring to breach their defences, millions of years old.

I was so tired, so very tired. Hands and feet were chilled until there was no feeling. My head was light and as thoughts relaxed, my stride became careless and clumsy. The roar of the wind bothered me less. I was calm. I plodded on. My legs were good at that. Just keep going, up or down, round and round, on a hill, on the flat, it didnt matter. Just keep going. But I was lost and losing it, and mountain madness was slowly gripping me. I was howling like a dog, swearing at the sky, jabbering nonsense. Repeating the words of the National Anthem in my head, over and over again, faster and faster, unable to stop, I knew I was in trouble. I had to get off this mountain.

A ONE-WAY TICKET TO BODMIN MY SANLUCAR DE BARRAMEDA CLIMBING BROWN WILLY AN ALTERCATION WITH A COW MR TWIT GIVING UP ROAD-KILL A SWISS SEDUCER THE MAGICAL 1,000-FOOT MARK A BACK GARDEN IN KENT

DAY 1 BODMIN TO OKEHAMPTON: 56 MILES

Brown Willy (Cornwall): 420m

Every journey has to start somewhere. Ferdinand Magellans circumnavigation of the Earth set sail from the Spanish port of Sanlucar de Barrameda. South Pole-bound Roald Amundsen went forth from the Norwegian capital Oslo. Neil Armstrongs mission to the Moon blasted off from the Kennedy Space Center.

Somehow Bodmin on a grey and blustery morning in May lacked that soul-stirring quality. I was on the starting line in Cornwall, the jagged foot of England that dips a toe into the Atlantic Ocean. Sitting on the town hall steps, I looked around for inspiration something to frame the moment or simply remind me this wasnt just another unremarkable happening in infinite time. Wind-blown chip wrappers tumbled across the road and a pair of seagulls pecked at the remains. An inquisitive mongrel sniffing at my bicycles front wheel was mid-cock when I shooed him away. Peering through a steamed-up caf window, I envied the hungry eaters devouring bacon, egg and beans. Behind them, on a TV in the corner, a weather forecaster pointed animatedly at a black cloud and three blobs of rain parked over the West Country. This was my Sanlucar de Barrameda.

I emptied the meagre contents of my rucksack onto the steps. I had embraced the thinking of the French writer Antoine de Saint-Exupry, who once declared: He who would travel happily must travel light. In went the essentials: a change of clothes, bar of soap and toothbrush, camera, road map, journal, a well-thumbed copy of Apsley Cherry-Garrards The Worst Journey in the World and a cheese sandwich. What more did I need? Unlike Amundsen, Armstrong and Magellan, Id be able to nip into the Co-op if Id forgotten anything.

It was time. There were no cheering crowds or rousing speeches only one anonymous spandex-clad cyclist setting off on a long journey. Tingling with trepidation and my heart thumping with freedom, I pushed off. Before long, Bodmin was gone in a blur and I was zipping merrily along high-hedged Cornish lanes towards Camelford. Next stop Shetland, the 60th parallel.

It had to be a bicycle journey. How else? I had exhausted the alternatives. Car too easy. Train too complicated. Bus too unpredictable. Helicopter too expensive. Walking too long. A bicycle fitted the bill. Here was a mode of transport fast enough to cover a respectable distance each day, but slow enough to absorb the changing sights, smells and sounds of the UK. When tarmac ran out, I would continue on foot. There would be no buses, no trains, no taxis and absolutely no lifts. The result? An entirely self-propelled journey between the highest point in each of the UKs historic counties the first of its kind. There were 92 counties and 92 summits. It was logical therefore that my journey must take 92 days and no longer.

There was, however, a stick in my spokes. My quest meant I had to reach five islands: Arran, Ireland, Orkney, Hoy and Shetland. To claim a truly self-propelled journey, I would have to swim to each. When Charlie Campbell set a new record for the fastest self-propelled traverse of the 284 Munros Scottish mountains higher than 914 metres in 2000, he swam from the mainland to Mull and the Isle of Skye. Campbell completed his feat in 48 days and 12 hours, but his swimming amounted to little more than two miles in relatively sheltered waters. I was faced with a swim across the Irish Sea to Northern Ireland, the Firth of Clyde to Arran, the Pentland Firth to Orkney, across Scapa Flow to Hoy, and 50 miles of ocean between Orkney and Shetland, twice. Aware that the notion of swimming such distances was ludicrous, I accepted that ferries would be a necessary evil.