Published by Nero,

an imprint of Schwartz Publishing Pty Ltd

3739 Langridge Street

Collingwood VIC 3066 Australia

email:

www.nerobooks.com

First published by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN TRADE in the United States a division of St. Martins Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010.

Palgrave and Macmillan are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries.

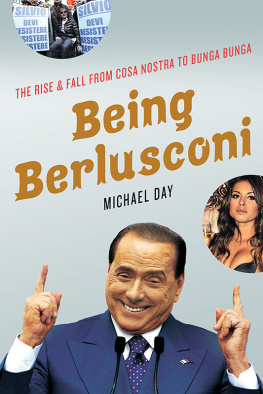

Copyright Michael Day 2015

Michael Day asserts his right to be known as the author of this work.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior consent of the publishers.

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry:

Creator: Day, Michael, 1966- author.

Title: Being Berlusconi: the rise and fall from cosa nostra to Bunga Bunga / Michael Day.

ISBN: 9781863957526 (paperback)

ISBN: 9781925203370 (ebook)

Subjects: Berlusconi, Silvio, 1936

Prime ministers--Italy--Biography.

Businesspeople--Italy--Biography.

Italy--Politics and government--1994

Dewey Number: 945.09311092

Cover and text design by Westchester Book Composition

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Heartfelt thanks to my brilliant friend, journalist and editor Jonathan Dyson, for his patient and thoughtful appraisal while I was writing the book. Special thanks as well to colleagues in Italy, including Jennifer Clark, Michele Novaga and many others at the Foreign Press Association offices in Rome and Milan. The help and advice of Italian journalists including Piero Colaprico of La Repubblica, Marco Travaglio and Marco Politi both of IlFatto Quotidiano, have also been invaluable. I should also thank the misanthropic wit of Fabio Vassallo, who encouraged my own irreverenceal punto giusto, I hope.

Several members of the magistrature have been extremely helpful, as have many parliamentarians, past and present, including Giuliano Urbani and Laura Garavini on the Anti-mafia commission. A number of Italian academics have also been very generous with their time and advice including Giorgio Sacerdoti and Emanuele Lucchini Guastalla of Bocconi University, Justin Frosini of the joint Johns HopkinsBologna University law department and Renzo Orlandi, also at Bologna University. Thanks, too, to the late James Walston of the American University of Rome, whose insights illuminated the murk of Italian politics for me and dozens of other journalists, and who is sorely missed by all of us. A shout-out, as well, to my agents, Jane and Miriam at Dystel & Goderich, and my editor, Karen Wolny at Palgrave Macmillan, for her patience and support, and also The Independent, which has let me wander around Italy for the past six years, witnessing so many interesting things. And finally, a huge thank-you to Annalisa and Giovanni and Enrico and Vincenzo and Elis and the hundreds of other Italians, who, through their kindness and cheerfulness, have made my time here so much easier and more enjoyable.

PROLOGUE

F or someone with such a dubious, albeit global, reputation, three-time Italian prime minister Silvio Berlusconi has collected a surprising number of awards during his controversial careeralthough were not talking Nobel Prizes. In 1977 he was made a Knight of the Order of Merit for Labor, in recognition of his entrepreneurial skills, hence his nickname Il Cavaliere (The Knight). Others followed: little-known knighthoods and gongs from Romania, Latvia and Poland, plus medals that youd be even less likely to shout about, from the likes of Saudi Arabia and Libya.

But Il Cavalieres last prize came on the evening of July 19, 2010, high up on the unlikely roof terrace above the main aisle of the citys cathedral, Il Duomo, when he received the Grande Milano award, a prize that marked him as the citys outstanding citizen of the year. The cathedral, a monumental tribute in marble to Northern Italian gothic, glowed pink in the setting sun as Milans great and good were hauled unceremoniously up the southern flank of the vast structure, 20 at a time, in a makeshift elevator, to see the prizegiving.

Pretty young stewards armed with clipboards and insect repellent welcomed politicians, journalists and hoary TV celebrities, some accompanied by young female companions tottering in six-inch heels, as they stepped onto the roof of the cathedral.

The sun sank and the eastern sky turned mauve, but the mercury didnt budge from the 86-degree mark. Swarms of mosquitoes danced around sweating guests, whose eyes darted around anxiouslyand in vainfor evidence of a bar.

If ever there was an awards ceremony in which the speeches needed to be brief, this was it. The provincial president, Guido Podest, seemed to think so: in his introduction of Berlusconi he gushed only briefly about the lascivious wheeler-dealers extraordinary charisma, exceptional human qualities and entrepreneurial skills, before welcoming the mogul onstage at the far end of the roof terrace, under the gaze of saints and gargoyles.

As with many of the good things to come Berlusconis way over the years, a payment figured in the proceedings; Podest had suggested as much when he praised the winners entrepreneurial skills. Shortly into his bloated acceptance speech, Berlusconi announced another 5 million ($6.5 million) a year from state coffers to maintain the vast cathedral, which, like the Golden Gate Bridge, is in a perpetual state of restoration.

Sitting at the far end of the ceremony with the other journalists, I felt my shirt stick to my back in a big wet patch as I turned to a reporter from La Repubblica and asked how long she thought the speech would last. Forever, she scowled.

Berlusconi has always loved the sound of his own voice: only a month earlier, noting his tonsils sensual quality, he employed them to launch the tourism ministrys latest promotional campaign for Italy. Now, in the suffocating heat, accompanied by a hundred inward groans among fidgeting guests, Milans man of the year, billionaire, criminal suspect and prime minister, had plenty to say.

He attacked the judges who were trying to make him accountable to the law, or what little there was left after hed manipulated it to his own ends for the best part of two decades; he talked up his largely inconsequential and frequently embarrassing performance on the world stagemaybe its because Im the oldest that Im the wisest and most knowledgeable, he said; he vowed to press on with plans to limit law enforcements use of wiretapsproposals that threatened investigations into organized crime; and he promised to rewrite the constitution.

Since that night in 2010 his plans to change the constitution have come to nothing; hes been kicked out of office for good and the judges have had the last laugh. In retrospect, the occasion and the speech have acquired a valedictory air, a final public gathering of the cronies and political allies who hitched a ride with the Silvio Berlusconi show. All of Milans conservative political establishment was present that evening, accompanied by a cast of characters ranging from the controversial to the ridiculous: post-fascist ministers, the citys high-society mayor, a seedy impresario, a pimping TV news anchorman, a Rottweiler newspaper editor. The unholy assembly had one thing in common: unquestioned loyalty to the media mogulall of them, in various ways and to different degrees, owed him something.

The moguls highly paid TV mouthpiece, Emilio Fede, was in the audience, as was Fedele Confalonieri, his college friend and faithful TV executive, who had been with him his entire, spectacular, scandal-struck career, since playing in a band with Berlusconi in their college years.