Copyright 2015 by Challian Inc.

Cover copyright 2015 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

All rights reserved. In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitute unlawful piracy and theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Hachette Books is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The Hachette Books name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.HachetteSpeakersBureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Unless otherwise noted, all photos are taken by permission from the private collection of Silvio Berlusconi.

As an American journalist who grew up in the 1970s, I have always been fascinated by the Frost-Nixon interviews, that famous series of face-to-face television interviews which British journalist David Frost conducted with President Richard Nixon in the spring of 1977, more than two years after Nixons dramatic resignation.

I was obsessed by Watergate, even as a teenager, the way kids today are obsessed by video games and Facebook. The drama. The intrigue. The White House tapes. The cover-up. The Washington Post scoops by reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein. The humbling of the president of the United States of America! The famous statement by Nixon that people have got to know whether or not their president is a crook. Well, I am not a crook.

I couldnt get enough of it. I craved the next installment in the Watergate saga. I consumed it like candy.

In the summer of 1974, at our summer house on a lake in upstate New York, I forced my thirteen-year-old sister to join me in watching the daily TV coverage of the impeachment hearings, which culminated in August in the dramatic resignation of President Richard Nixon. We watched him resign and then we watched him say good-bye to the White House staff, with that bizarre salute, that wave of despair he offered to the American people before boarding his helicopter on the White House lawn in order to fly to Andrews Air Force Base and then begin the long flight back to California, in disgrace.

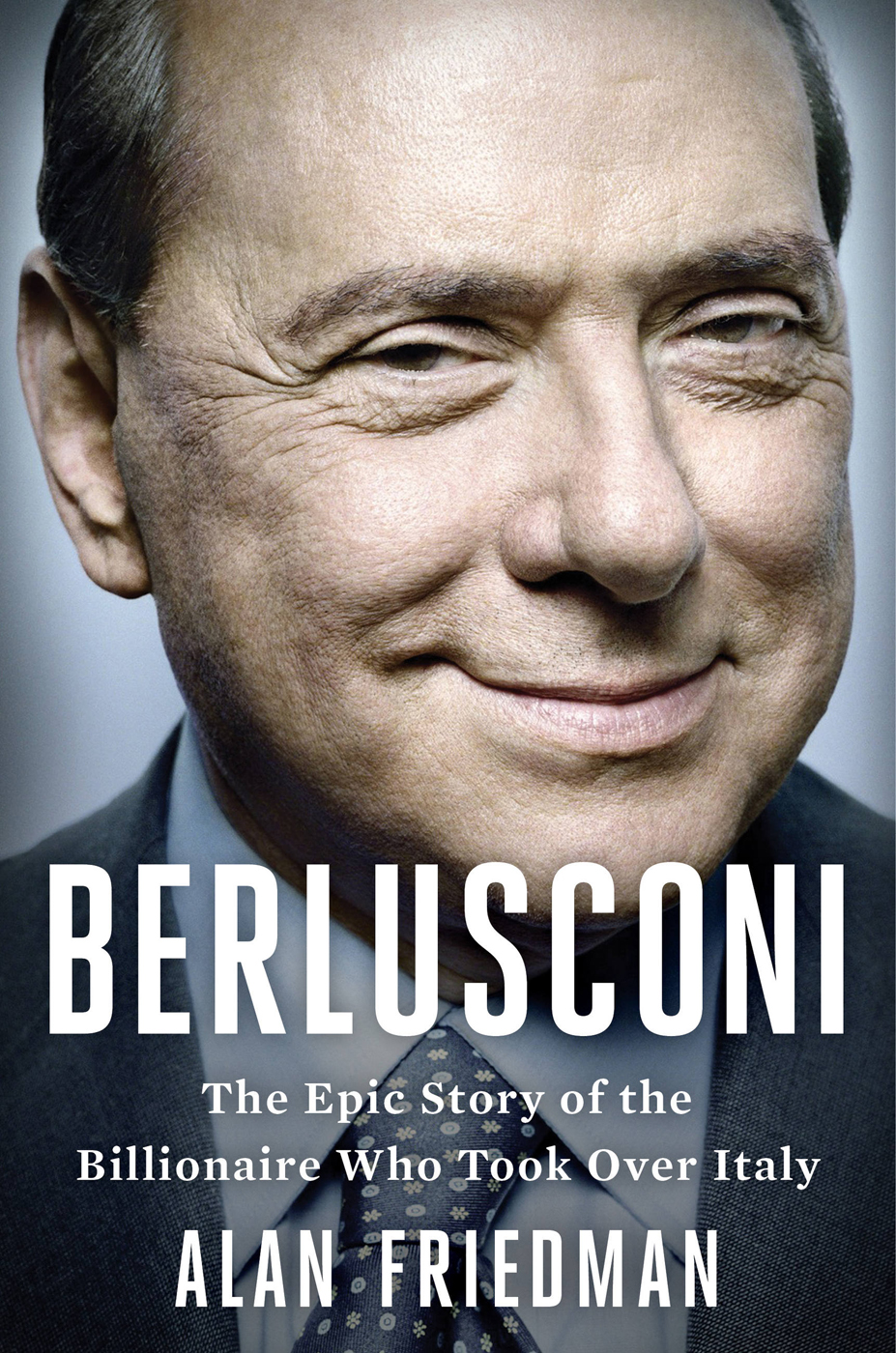

All of these memories came flooding back in early 2014 when my Italian publisher at Rizzoli in Milan first suggested I try to get Silvio Berlusconi, the most colorful and controversial leader in modern Italian political history, to agree to tell me his life story. I had known Berlusconi for thirty years, from my early days as a foreign correspondent in Milan for the Financial Times of London in the 1980s. At times I had been a fierce critic of Berlusconi, then later I became intrigued by his personal story. This was not only because of his alleged bunga-bunga parties and the corruption trials but because of the extraordinary, epic-like story of his life. I followed closely the events surrounding his political downfall in 2011, his conviction in 2013 on tax fraud by Italys Supreme Court, and his eviction from the Italian senate later that year. Yet even today Berlusconi still casts a long shadow in Italy, so I remained curious about the story.

When I first went to ask him if he was interested in cooperating on this book, I had low expectations. It was late on the morning of March 12, 2014. I went to see him at his ornate residence in Rome, the second floor of a seventeenth-century palazzo, resplendent with frescoed ceilings and gold tapestry-covered walls. Berlusconi, now seventy-seven years old, seemed to like me, mainly because I was an American (and therefore not an Italian journalist with preconceived notions) but also because he felt vindicated by another book I had written about Italian politics, a result that had not been my aim in life.

I informed Berlusconi that I had decided to write a book about his life story and I proposed that he provide me with full cooperation and unfettered access to archives, family members, friends, business partners, and political allies. He first gave me a long stare in the eye, then told me that over the past decade he had refused at least fifteen similar requests. I told him this would not just be a book but also a series of ten or fifteen television interviews, modeled on the famous Frost-Nixon interviews of 1977. He kept staring at me, muttered something about understanding that today everything needs to be multimedia, and then suddenly he proffered his hand. We shook hands, and he was very clear in what he then said: I trust you to tell my story in a fair and honest way. I thanked him for his confidence and informed him directly: This will not be hagiography. I will not write the story of a saint, or of a victim, I will not be hostile but I will not do you any favors. I will write in a fair and balanced way the story of an extraordinary life, as I see it, but with you answering my questions about each chapter of your life, and all of it taped on video.

Silvio Berlusconi agreed to my terms. Later that day one of his advisers shared his opinion as to why Berlusconi had said yes: His world is collapsing around him, and while he dreams of making another political comeback, he sees this as his legacy, with you as his witness, as the first and last journalist with whom he will share his life story, in his own words.

In the seventeen months that followed, from the tumultuous spring of 2014 until the end of the summer of 2015, I observed Berlusconi up close, mainly at home. We had numerous conversations and interviews during a period full of emotion for Berlusconi, a period marked by a fair amount of bitterness and defeat and at the same time a period of constant planning for a political comeback. In some ways I watched a real-life psychodrama playing out before my eyes. I was also privileged by the unusually free access, which allowed me to really get to know the man, and his default mechanisms, his thought patterns, his pet peeves, even his favorite anecdotes and jokes.

For a while, each time I went to interview him, whether at the palazzo in Rome or in the garden of his spectacular villa in the village of Arcore, on the outskirts of Milan, something bad was happening. He was emotional at times, usually in the run-up to another court ruling in one of his many cases. Often, after the interviews, he would ask me to speak in private, and he would pour out his heart, speak of his enemies, or confide in me his concerns, his hopes, his ambitions.