Contents

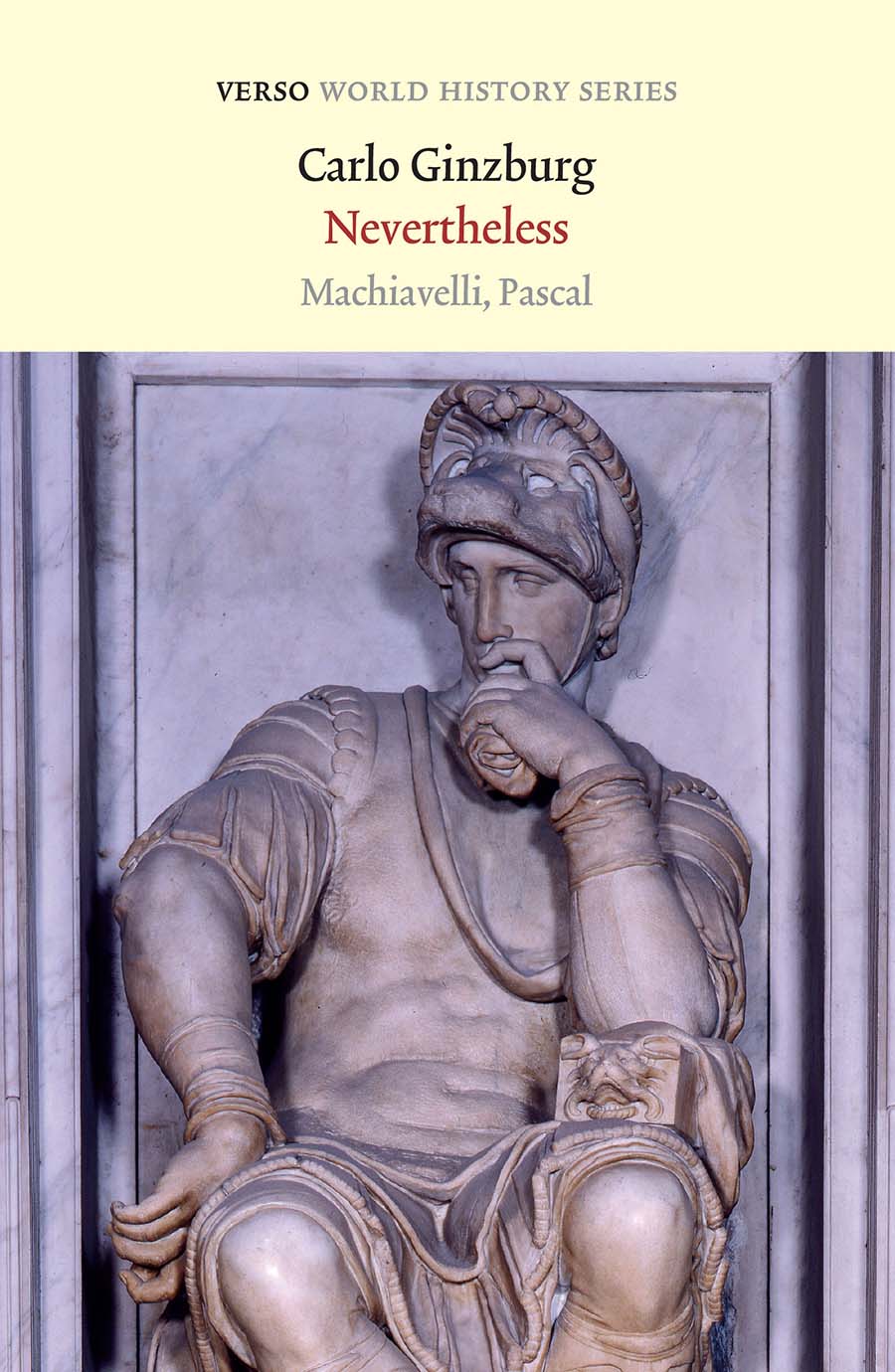

Nevertheless

Nevertheless

Machiavelli, Pascal

Carlo Ginzburg

Translation editor Gregory Elliott

First published in English by Verso 2022

Originally published in Italian as Nondimanco:

Machiavelli, Pascal, Adelphi Edizioni 2018

Carlo Ginzburg 2018, 2022

Translation Chapter 7: Francis Mulhern 2022

Preface, Chapter 7 postscript, Chapter

10 and Appendix: Gregory Elliott 2022

The translation of this work has been funded by SEPS

Segretariato Europeo per le Pubblicazioni Scientifiche

Via Val dAposa 7 40123 Bologna Italy

seps@seps.it seps.it

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author and translators have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-83976-014-3

ISBN-13: 978-1-83976-015-0 (UK EBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-83976-016-7 (US EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021947716

Typeset in Sabon LT by Hewer Text UK Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY

Contents

1. First things first the subtitle: Machiavelli, Pascal. Why the comma?

The comma is an ambiguous punctuation mark, indicating either a conjunction or a disjunction. In this instance, both. Nevertheless begins by arguing that Machiavelli learned from medieval casuistry how to reflect on rules and exceptions and ends by analysing Pascals savage polemic against casuistry. What makes it possible to ponder Machiavelli and Pascal conjointly?

The answer is: political theology a notion the contemporary reader immediately associates with Carl Schmitt. Here is the celebrated opening of chapter 1 of his book Political Theology (1922; 2nd edition, 1934), followed by the no less famous start of chapter 3:

Sovereign is he who decides on the exception

All significant concepts of the modern theory of the state are secularized theological concepts not only because of their historical development in which they were transferred from theology to the theory of the state, whereby, for example, the omnipotent God became the omnipotent lawgiver but also because of their systematic structure, the recognition of which is necessary for a sociological consideration of these concepts. The exception in jurisprudence is analogous to the miracle in theology.

And now Pascal (Penses, fragment 280):

States would perish if their laws were not often stretched to meet necessity, but religion has never tolerated or practised such a thing. So either compromises [accommodements] or miracles are needed.

As is well known, Schmitt often refrained from citing his sources, even when he read them polemically. As far as I know, neither Schmitt nor his countless followers, commentators and critics have ever mentioned this pense of Pascal.

Political theology is not a neutral category. In this case, as always, it is necessary to analyse the research tools, bringing to light their presuppositions and implications.

2. In a famous passage (The Prince, chapter 6), Machiavelli pays an ambiguous tribute to Moses (and his great master), comparing him with more or less mythical sovereigns of secular antiquity:

However, to come to those who have become rulers through their own ability and not through luck or favour, I consider that the most outstanding were Moses, Cyrus, Romulus, Theseus and others of that stamp. And although one should not reason about Moses, as he was a mere executor of things that had been ordered for him by God, nonetheless he should be admired even if only for that grace which made him deserving of speaking with God. But let us consider Cyrus and others who have acquired or founded kingdoms. They will all be found remarkable, and if their actions and methods are considered, they will not appear very different from those of Moses, who had such a great master.

Moses, Cyrus and Theseus return at the end of The Prince (chapter 26) when Machiavelli evokes the present situation of Italy, more enslaved than the Hebrews, more oppressed than the Persians, more scattered than the Athenians. Machiavelli The reference implicit in this coolly rhetorical outburst was the miraculous election of Cardinal Giovanni de Medici, who became Pope Leo X.

Obviously, we are far removed from Pascal. For him miracles something God alone, the God of the Bible not of the philosophers, could perform possessed a profound, literal, existential significance. But at the same time, as we saw in the fragment cited above, for Pascal the miracle was comparable to the exception to the political and moral rule hence to Machiavellis nevertheless. Chapter 7 is devoted to an analysis of Pascals reading of Machiavelli.

3. The first seminar in which I had the good fortune to participate was Arsenio Frugonis on Il principe at the Scuola Normale di Pisa in 19571958 (I was eighteen). Almost fifty years later, in January 2002, I read The Prince with my students at UCLA. The choice of this subject, following the attack on the Twin Towers of 11 September 2001, seemed obvious. Secularization was an open problem, which demanded reflection. In the months preceding the seminar, I began to explore the possible link between Machiavelli and casuistry: a research scheme possibly triggered, without me having realized it, by the gesture with which Benedetto Croce dismissed it, after having evoked it. The research programme outlined in chapter 1 has been pursued in the subsequent chapters from different, partial angles, but not, I hope, irrelevant ones. Also a discussion (here virtually absent) of Machiavelli and the republican tradition will, if I am not mistaken, have to settle accounts with the interpretation proposed here.

Over the years, this research trajectory has intersected on the one hand with the coordination of a project on the comparative history of casuistry, funded by the International Balzan Prize Foundation, and on the other with the invitation to deliver the Tanner Lectures at Harvard. In both instances I presented the results of my research on Pascals Provincial Letters and their echoes. Machiavelli drew me towards Pascal, including the Pascal who was a reader of Machiavelli the most religious Machiavelli referred to (as we shall see in chapter 9) by a reader of the Provincial Letters. Pascal, Machiavelli.

I am grateful to my students at UCLA; the Universit degli Studi, Siena; and the Scuola Normale Superiore, Pisa, who many years ago participated in my seminars on Machiavelli (in particular, Fabio Paglieri and my friend Carlo Pincin for their contributions to the Sienese seminar on the Ghiribizzi); Quentin Skinner for his extraordinary intellectual generosity; Homi K. Bhabha for having invited me to give the Tanner Lectures, reworked here in chapters 79; Robert A. Maryks for having agreed to comment on them at Harvard; Ann Blair and Robert Darnton for their warm hospitality; Marcelo Barbuto for the bibliographical supplementation of chapters 1 and 7; Suzanne Werder (Balzan Foundation) for having made the project on the comparative history of casuistry possible; Laura Tita Farinella (Biblioteca dellArchiginnasio, Bologna) for having guided my research on the reception of Pascal; Monsignor Alejandro Cifres (Archive of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith) and Marco Grillo (Vatican Secret Archive) for having allowed me to consult the documents from the trial of Galileo Galilei; the Vatican Apostolic Library in Vatican City and the Royal Library of Turin, which permitted me to reproduce pages of manuscripts in their possession; Stefano Zamponi for having replied, with the competence peculiar to him, to my questions on the documents of the Galileo trial; Perry Anderson, Franco Bacchelli, Lucio Biasiori, Maria Luisa Catoni, Gaetano Lettieri, Martin Rueff and Sanjay Subrahmanyam for their valuable criticisms. I recall with regret Francesco Orlando, who many years ago nudged me towards Pascal.