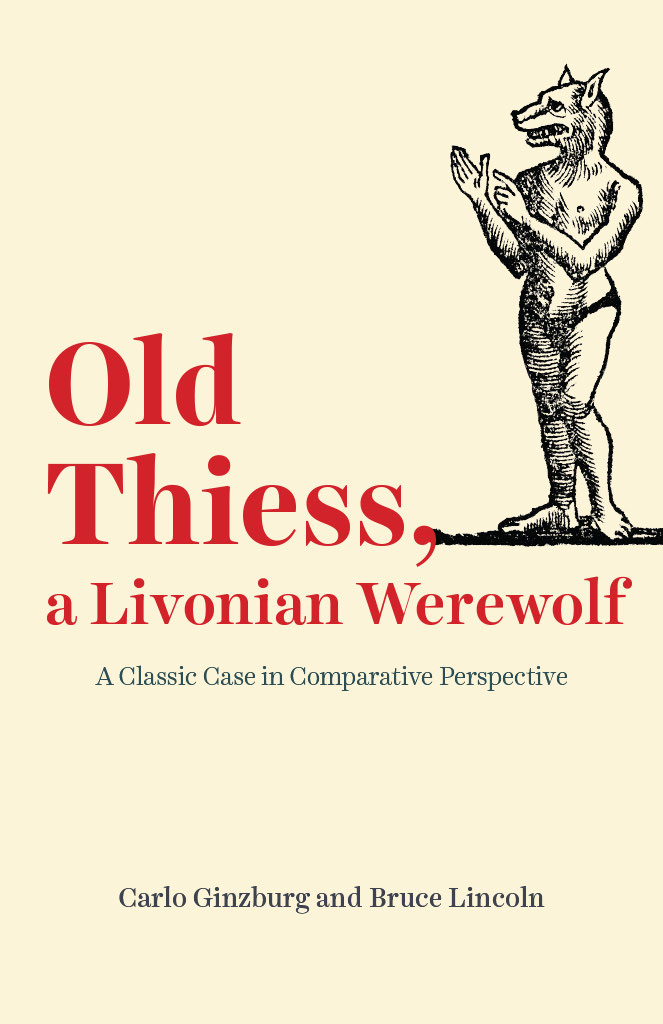

Old Thiess, a Livonian Werewolf

Old Thiess, a Livonian Werewolf

A Classic Case in Comparative Perspective

Carlo Ginzburg and Bruce Lincoln

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2020 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 East 60th Street, Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2020

Printed in the United States of America

29 28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-67438-4 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-67441-4 (paper)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-67455-1 (e-book)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226674551.001.0001

The University of Chicago Press gratefully acknowledges the generous support of the Divinity School and the Franke Institute for the Humanities at the University of Chicago toward the publication of this book.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Ginzburg, Carlo, author. | Lincoln, Bruce, author, translator. | Hfler, Otto, 1901

Title: Old Thiess, a Livonian werewolf : a classic case in comparative perspective / Carlo Ginzburg, Bruce Lincoln.

Description: Chicago ; London : The University of Chicago Press, 2020. | Some text translated from German. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019029998 | ISBN 9780226674384 (cloth) | ISBN 9780226674414 (paperback) | ISBN 9780226674551 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Old Thiess, active 17th centuryTrials, litigation, etc. | WerewolvesLivoniaHistory17th century. | WerewolvesLivoniaReligious aspects. | Trials (Witchcraft)Livonia.

Classification: LCC GR830.W4 G56 2020 | DDC 398.24/54094798dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019029998

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

Contents

Bruce Lincoln

Carlo Ginzburg

Otto Hfler; translated by Bruce Lincoln

Carlo Ginzburg

Bruce Lincoln

Figures

Tables

BRUCE LINCOLN

I

Although werewolves abound in folklore, fiction, film, and rumor, relatively few people have been formally charged with being werewolves, and even fewer have accepted that word as an accurate description of themselves. Most of our information for such realia comes from surviving court records that preserve fewer than three hundred cases. And like most defendants of whatever sort, the majority of accused werewolves initially denied the charges. When tortured, however, they regularly confessed, echoingand thereby reinforcingboth learned and popular stereotypes. Cumulatively, these records permit a historian to understand what European theologians and jurists of the early modern period believed about werewolves, the power these people had to project those beliefs onto others, and the price some poor souls paid as a result.

The case that concerns us is strikingly different.

II

In October 1691, an elderly Latvian peasant sat patiently as he waited to testify at the trial of a fellow villager accused of stealing from the local church. Before he could do so, however, another witness laughed at the idea of this man swearing a solemn oath, since he was commonly known to be a werewolf. And when the man, known to everyone as Old Thiess (a nickname for Mtiss, the Latvian equivalent of Matthew), confirmed it was so, the court turned its attention to him.

Hours of questions and answers followed in a high-stakes struggle between decidedly unequal forces. For their part, the judges, and then the village pastor, pressed Thiess to acknowledge that as a werewolf he had given himself to the devil. This he staunchly denied, while admitting that he could change himself into a wolf and that he had, along with fellow werewolves, stolen livestock in that form. Most surprisingly, he described how his werewolf band entered hell at certain times of the year, not to serve Satanas the judges insistedbut to fight him, with the well-being of people, herds, and crops dependent on the outcome.

Thiess sought not to deny the specific charge but to correct his accusers prejudices and instruct them on the true, benevolent, distinctly non-Satanic nature of werewolves, a group he understood far better than they. At times, the judges were shocked by the old mans explanations; at others, they reacted with mixed amusement, curiosity, confusion, and frustration. Unable to obtain a confession or adduce evidence that would confirm the key point of diabolic collusion, they failed to reach a verdict on so difficult and doubtful a case. Accordingly, they decided to have the case reviewed at a later session of the court, with different judges presiding. Apparently, those judges based their verdict on the trials transcript, whichfortunately for uswas then preserved in the courts archives.

III

For more than two centuries, that transcript sat in the archives of the High Court of Dorpat (todays Tartu) until Hermann von Bruiningk (18491927), Latvias foremost specialist in the nations premodern history, made it the centerpiece of his pioneering article The Werewolf in Livonia. Von Bruiningk, exceptionally adept at archival research, was a man of strong nationalist sentiments and proud of his descent in a line of Baltic German nobles. Writing in 1924, shortly after the Baltic republics gained independence, he wished to rebut longstanding stereotypes that made Livonia (a historical region encompassing parts of todays Latvia and Estonia) the classic home of werewolves, much as Transylvania is associated with vampires. On the basis of a thorough investigation of church and legal records, which uncovered barely a trace of werewolf lore before the middle of the sixteenth century, von Bruiningk argued that demonological theories originating elsewhere in Europe had made their way to the Baltic around that time via the learned writings of Olaus Magnus (Swedens last Catholic archbishop) and others. Through the lens of these imported theories, the latent (and benign) traces of pre-Christian religiosity were misconstrued as diabolical dangers.

As von Bruiningk wrote,

In Christian times, when people acknowledged the existence of the heathen gods only in order to identify them with the devil, the heathen cult was represented as the horror of devil worship, the servants of the gods as the devils servants, and the belief in witches began here, with the idea of people who, with Satans help, change into wolves out of pure bloodthirstiness.

While werewolf beliefs were an ancient superstition, well attested in legends and folklore throughout all Europe, von Bruiningk found that court records seriously exaggerated and prejudicially distorted the phenomenon in ways that reflectedand also helped maintain and justifythe asymmetric power relations that played out in the dynamics of accusation, denial, torture, and confession. Even so, he did not believe the image of the werewolf found in court records was something the demonologists had fabricated ex nihilo. Rather, following Wilhelm Hertzs Der Werwolf, the most authoritative work on the subject in his era, he imagined that in the pre-Christian Baltic, as elsewhere in Europe, Aryan religiosity included divine beings who mediated the distinction between human and animal, combining the powers and good qualities of both:

Next page