Alfred knew before he had been in the mountains three hours that they meant to harm him.

The game had gone on too long and when they went to tie him up he was too drunk to resist. Limp and passive, he felt pulled along in the direction this thing was going. It was as if it were a play and all the boys were characters who had performed this many times, who knew all the lines and where to stand, where to place the hood and when to light the fire.

A lot had happened the blond boy called Hadrien had delivered a lengthy speech, some of which sounded not to be in English, a kangaroo had been dismembered, and a couple of the boys had been sick by the time Alfred was freed from the restraints and ran out into the dark bush.

For one long, exhilarating moment it was as if he had woken up from a deep sleep. Strange and powerful chemicals surged through him, making him forget his cuts, welts and humiliations. He was Superman as he soared across the rocky paths, through the trees, over rocks, across a creek, and then down, down, down, down, down to a place where he merged with the night.

Toby studied his teammates as they got out of the car and stretched their legs after the two-hour drive. They were all dressed in their college rugby jumpers and shorts, like it was a uniform. Their faces also seemed uniform blank, world-weary. Nineteen, twenty years old and they had seen it all.

Not him, though. He was not like them. Even though he would turn twenty-one later this year, Toby was still experiencing sharp, pleasurable shocks of discovery.

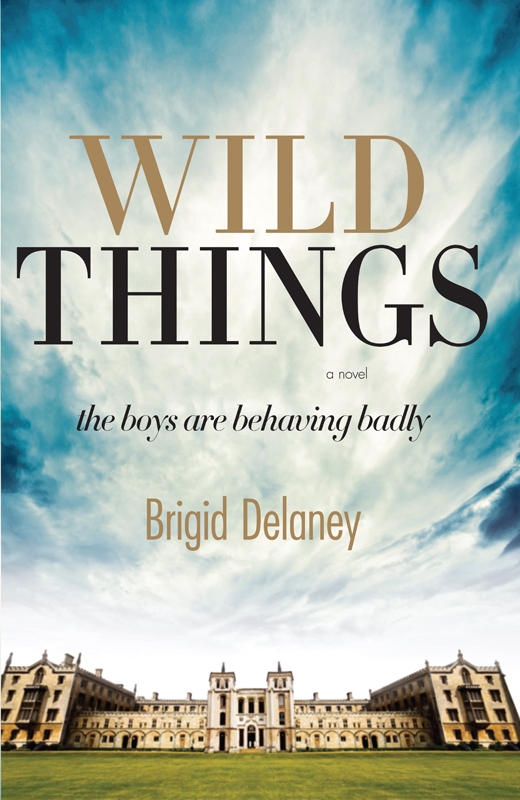

From the day he had arrived at St Antons it was like the world had remade itself. There was the college itself, a revelation after the portable classrooms of his country high school, with its library that was once the assembly hall, the scuffed grass on the oval. He had never realised before how makeshift his old school had been; it had none of the weight of history of St Antons, where the chapel had always been the chapel and always would be, and where it was unthinkable that the gothic dining hall would ever be used for another purpose an art studio, say, or a performance space.

From the outside, with its high stone walls, St Antons resembled a fortress, but inside was a dazzling quadrangle as brilliantly green as ferns backlit in the tropics. Around it were arranged freshmen rooms, a chapel and an archway that led to another, smaller quadrangle, with rooms belonging to more senior students. The third quadrangle housed the tutors quarters, the dining room and a second chapel. Behind the chapel were a velvety playing field, a pocket of farmland and a river. The St Antons Master lived in a gabled cottage, set off to the side of the college beside a pond filled with gliding swans. The other colleges were also hemmed in by the river and by walls of stone, and they too had their own dining halls, chapels, computer rooms, tutors lodges, playing fields, libraries, study rooms, billiard rooms, discussion rooms and smaller chapels for prayers and confession.

St Antons was famous for the animals that grazed on its lawns lambs, waterfowl, peacocks and pheasants. The job of feeding the animals went to members of the Senior Common Room. One might wake particularly early and see Dr Bath, the swollen-hipped modern history teacher, wandering among the peacocks and geese in his white nightgown and pale bare feet, his eyelids heavy, his lips mumbling either morning greetings to the birds, ancient battle speeches of Constantinople, or lines from a Gerard Manley Hopkins poem.

The college was home to two hundred students, both male and female, most of them aged between seventeen and twenty. There were a dozen tutors, a chaplain old, feeble Dr Williams and the head of the college, Locke Greenway, whom everyone just called the Master.

On his first day, more than two years ago now, Toby had stood in the first quadrangle gawping at the buildings, at the animals, up at the spires, down at the lawn, at the other freshmen who moved around him with boxes and bags, in groups already, friends already. They didnt stare like hinge-jawed hicks at the llama being led by Dr Bath towards the river, nor were they conspicuously, almost violently alone, holding a much-loved cricket bat, a Gray-Nicolls Viper, the veteran of many games with his brothers. Yet still he gawped in mad love with the place already but panicked that he did not belong here and would be found out at any moment.

Do you play cricket? A boy of about Tobys age had materialised by his side, wearing frayed khaki shorts, a navy-blue polo shirt, boat shoes and a cap bearing the legend Wakelin Steel Guangdong Province .

Yes do you?

The boy nodded. Cricket tragic, actually. I spent the whole summer at the Test matches. Im Ben.

Toby.

You should try out with me for the team, said Ben. Theres a bunch of us from my school going down to the oval this afternoon. Ill introduce you He was pointing to a group of boys gathered by the pond with cricket bats and pads. They were all dressed like Ben except for a small blond posh-looking boy who was, quite eccentrically, wearing a suit.

That first afternoon unfolded like a beautiful dream: a day of miraculous sixes and a stunning catch and the late afternoon sun toasty on his back, and later a strange dark English-style pub called the Red Lion, with a low ceiling and crossed rowing oars nailed above the bar, where he and Ben sat, drinking and talking easily. The feeling that he was an intruder, a lurker on the edges, slipped away so quickly that Toby felt strangely but happily unmoored from the past. His anchor was up. Nothing significant in his life had happened, or was fondly remembered before he got here.

As more time passed, he sometimes forgot that he wasnt from a rich family like Ben and the others. On his first visit back home at Easter break Tobys father warned him that it was more dangerous to hang around people with a lot of money than to have lots of money yourself, as it gave you an expectation of a certain lifestyle without the means of achieving it. It could lead to one of two things perpetual frustration and bitterness at what you didnt have, or indentured servitude in a corporate law practice or merchant bank to feed your engorged sense of entitlement.

Unhappiness and compromise are what come from that, Tobys dad said. You are unhappy because you cant get what you think you deserve and so you compromise yourself in order to get it.

So I guess you can feel smug about being poor and having a boring life because youve never compromised, Toby retorted.

He went home less frequently after that. Instead he visited the beach houses of his new friends Ben, Charlotte or Julian during the summer holidays. In winter he went on skiing trips with Julian, Roman, Charlotte and Ben.

Ben had become like another brother. By second year the new fresher girls had difficulty telling them apart. Toby had darker hair and was two inches taller, but through playing the same sports, studying for the same degree, having the same friends and sleeping with the same girls they became almost indistinguishable. Not that Toby minded: when there were two of them, it made him feel stronger.

Yet some transitions into this new world did not come easily. The boys from Bens school one of those famous and expensive schools where the boys all called each other by their surnames (I was at school with Leeson for ten years, and I dont even know his first name! said Ben) were obsessed with some secret male-only club from the 1920s that their great-grandfathers had belonged to. Hadrien the posh boy in the suit Toby had noticed on his first day called it the Savage Society and would occasionally produce a red leather-bound book, in which complex initiation rituals were recorded in cursive script, and which they performed during the cricket away trips. In the past two years, Toby had been pressured to eat peyote (which made him throw up), have some hulking fourth-year threaten him with a dildo (waving it close to his face saying, You like cock? You like cock? You like cock, yeah!), smoke opium from an eighteenth-century pipe Hadrien had found at some antique store in Shanghai and walk forty-six kilometres in the bush without his clothes.