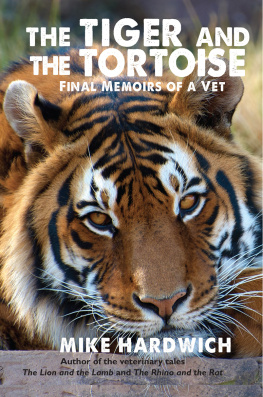

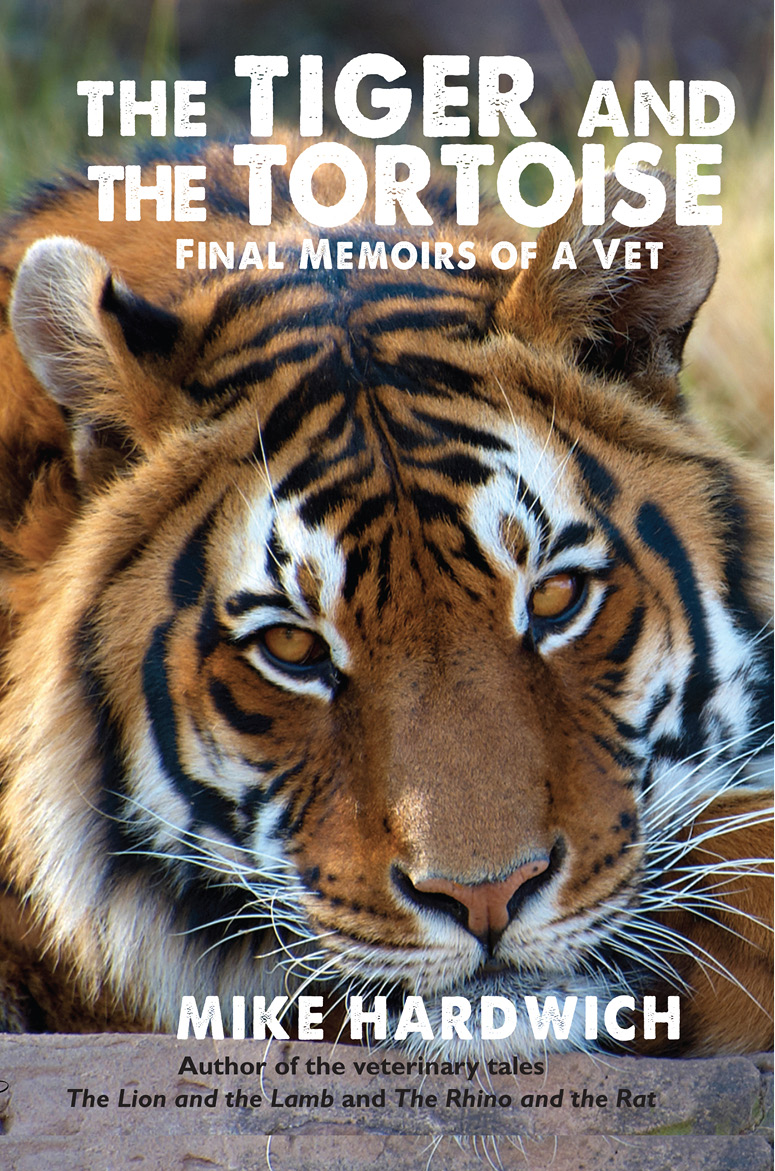

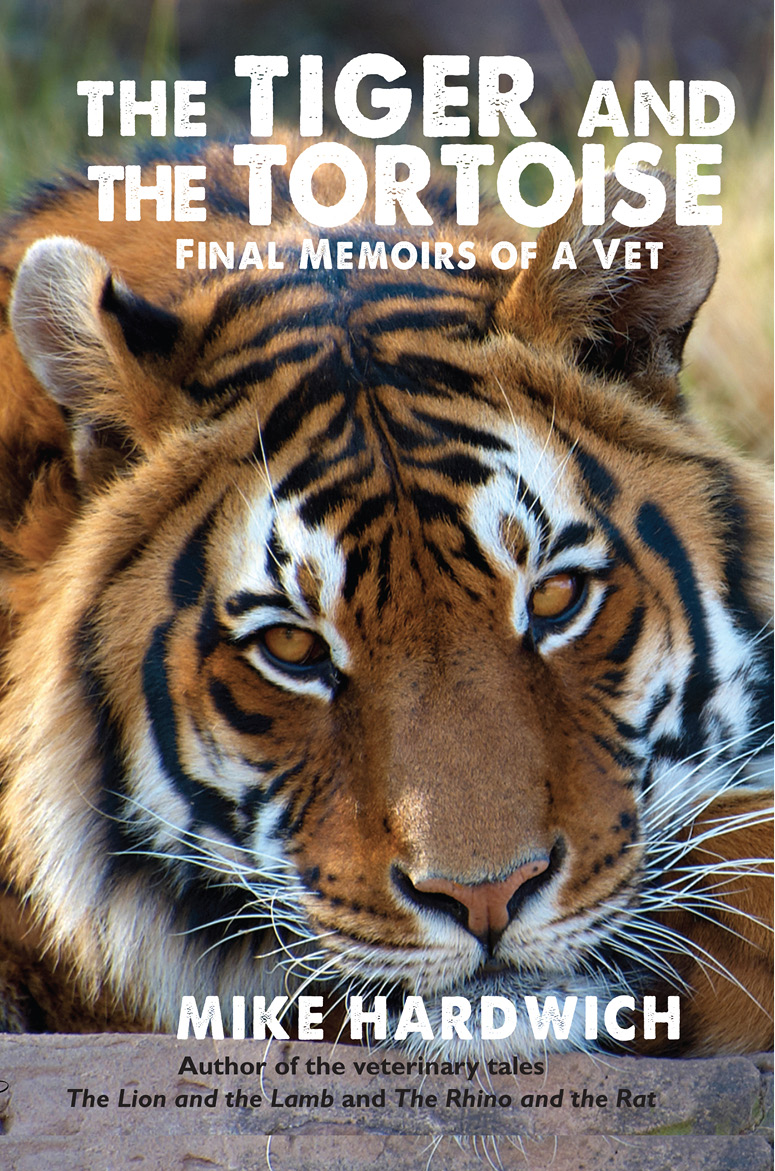

The Tiger

And The Tortoise

final Memoirs of a Vet

MIKE HARDWICH

First published by Tracey McDonald Publishers, 2014

Office: 5 Quelea Street, Fourways, Johannesburg, South Africa, 2191

www.traceymcdonaldpublishers.com

Copyright Mike Hardwich 2014

Illustrations Shirley Thurbon

All rights reserved

The moral right of the author has been asserted

ISBN 978-0-620-60213-6

e-ISBN (ePUB) 978-0-620-60214-3

e-ISBN (PDF) 978-0-620-60215-0

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED TO FOUR AMAZING LADIES

AND SIX DECEASED CLASSMATES

The compassion these ladies have for animals is astonishing

they are happy to compromise their own comfort for the

welfare of creatures that cannot speak for themselves

Susan Clarke

Gill Organ

Yvonne Michelin

And my daughter, Dale Gait

And to six late fellow students who did not make our 40th anniversary

James Morris

Jim Reid-Rowland

Herman Scherer

Rynald Lawrenz

Johan Uys

Darryl Baxter

CHAPTER 1

AMANZI, THE WATTLED CRANE

So far it had been a blissfully peaceful weekend. A restful break such as this is what every vet dreams of. The standby vehicle had remained stationary and the telephone had been silent. The veterinary hospital was empty even though the days of the last week had been very busy.

Actually, it seemed too good to be true.

As it happened, it was.

At about half past three on Sunday afternoon the phone suddenly and blaringly shattered the tranquillity. It was Paul, one of my regular clients, calling from the home of a friend of his.

Hi, Mike, please speak to Ann, she has a major problem, he said without any preliminary chit-chat.

Ann was from the Hlatikulu crane sanctuary and she wasted no time either. I am in a very difficult position, Dr Hardwich, she said right away. I have a male wattled crane that has what I think is a broken wing and the vet I would normally call is unavailable. When I saw the bird this morning I found that his wing was hanging unnaturally in spite of the fact that he seemed otherwise to be fine, so I ignored it. However, this afternoon the appendage appears to be hanging a lot lower and looks a lot worse than it did before. He also has flecks of blood all over his feathers.

To be honest I did not want to get involved. Birds are finicky to deal with at the best of times and this particular one was a long way away, which would make treatment and follow-up care a logistical nightmare.

I suggested to Ann that she catch the crane and strap the wing to his body as best she could so that it was immobilised. Then get your vet to look at him as soon as he is back in the morning, I advised.

This was unwelcome advice and it was quickly apparent that Ann was not going to accept it.

Mike, I cannot and will not do that! she said emphatically. This bird is the only breeding male in captivity, and there are only about two hundred and forty live birds left in total. They are classified as critically endangered. He has also proved himself to be a successful breeding partner and he deserves the best possible treatment.

I was only partially aware of the plight of these beautiful southern African birds and how their wetland territory was rapidly being destroyed, but I knew about the Hlatikulu sanctuary, although I had never had the time to visit it. I could not deny my concern for the creature and now my interest had been piqued with what Ann was telling me. I had a rapid change of mind. I realised I did want to get involved after all.

Various possibilities flooded my mind, but obviously I couldnt determine what needed to be done over the phone. I would need to examine the bird thoroughly before I could help it. Ann had also mentioned that these birds were extremely aggressive and were inclined to defend their chicks vigorously. This could be an additional problem because where there is a highly developed protective system in place such as this was sure to be, there is also a good chance of shock setting in after an injury which could cost the valuable bird its life.

After a fairly lengthy discussion with Ann I decided that the best option was for her to put the bird in a travelling crate and bring it to my surgery. Paul would be on hand to help her. She was an hour and a half away by road. There was little point in my travelling out to the sanctuary because I did not know what equipment I might need. The crane might need a gas anaesthetic and almost certainly X-rays.

After agreeing to meet with her and the injured bird at my rooms, I drove the 45-minute trip there. On the way, I was thinking hard how I could best proceed to help the bird. Many of the problems I had wrestled with dissolved once Ann arrived. She was a well-known authority on cranes, and although not a vet, had a very good idea of what needed to be done. She also had a list of websites we could visit on the internet to get information and necessary treatment protocols. She was able, well prepared and very helpful.

The bird was named Amanzi, the Zulu word for water in English. He was a male adult and, after losing a mate a few years earlier, had taken a new love and started an affaire de coeur with her. With his current consort he had successfully sired two healthy chicks. In a natural environment these birds only raise a single chick per breeding season. Usually two eggs are laid at a time but the second hatchling is pushed out of the nest and only the first is cared for by the parents. Ann had removed the second chick sired by Amanzi and was raising it successfully by hand. In fact the one she was caring for was already larger than the one the biological parents were rearing! But both were doing well and were healthy and robust. The parent birds are characteristically extremely protective and I wondered if this might have been the cause of the males apparently broken wing. He could have thrown himself against the fence of the enclosure in an effort to repulse an attack of some sort, become tangled in the wire and broken his wing in the process.

Between us, Paul and I managed to manoeuvre the travelling crate carefully from the vehicle and into the hospital prep room. There was only a tiny viewing aperture in the box and this was not adequate for me to inspect the patient properly. Paul opened the crate and Ann caught the distraught bird in a skilled manner, quickly slipping a hood over its head. The hood looked very much like a golf club cover to me. Amanzi settled down considerably and grew quiet once his eyes were in the dark.

Having searched the internet, I had a reasonable idea of what I was up against, although the most important thing that I had learned from experience was that each animal is a unique individual and each may act unexpectedly. I had to be cautious with each and every case and avoid generalising.

Next page