No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publishers.

Tortoise. (Animal)

1. Tortoise 2. Animals and civilization

I. Title

597.92

Fittest not Fastest

Tortoises look and are old, almost mythical creatures. They are primeval, the oldest of the living land reptiles, their age confirmed by fossil remains. Tortoises are the surviving link between animal life in water and on land. Some 280 million years ago, late in the Carboniferous period when coal was being formed from rotting vegetation in forest swamps, reptiles were the first creatures to emerge and breed on land.

So named from the Latin reptilis (creeping), reptiles as a class developed to survive in a dry environment. Fins became strong legs; they had tough skins, jaws that enabled them to eat plants, and they laid durable eggs. Their presence on land led to a cycle of improvement. For example, as herbivores they ate seeds that passed undamaged through the gut and were deposited complete with fertiliser, thus increasing the animals food supply. Gradually they came to be the lords of creation, ending the dominance of marine creatures within the animal kingdom. The Age of the Reptiles was a long one, from about 245 to 65 million years ago. During that time, though, many species died out, to reappear only as museum skeletons or reconstructions in virtual reality. Tortoises, which emerged early in that period, have survived for some 225 million years. They are living fossils. Hardy, self-contained creatures, they have endured aeons of major changes,and on a world scale survived geological upheaval, volcanic activity and climatic swings.

Resembling fossils, tortoises have also inspired jokes about mating with rocks.

It is not difficult to see why they have survived. The obvious reason is that they have an external skeleton, a bony shell that boxes them in. This evolved over time. Originally, to protect their flesh, the creatures grew a series of horny plates or scales. In response to threats these became larger, eventually joining together to create the shell as we know it today. During this process, the skin and muscles of the back and breast had a diminishing function, gradually wasting away to the point where the shell was resting on the bones. Ultimately, most of the internal bones fused with the living bone casing, leaving the bones of the neck and tail free.

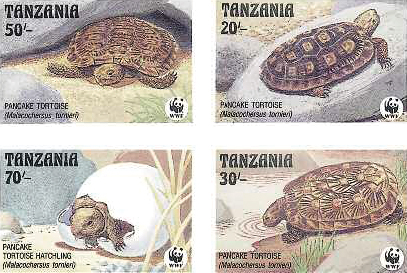

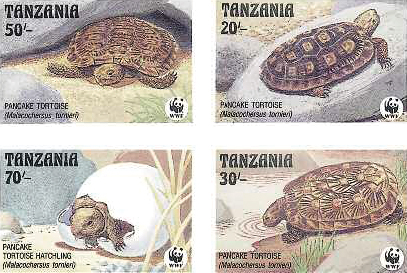

Most tortoises have a high domed shell, a carapace that is strong and hard to crack. A literal translation of the German Schildkrte is shield-toad, and of the Hungarian teknsbka bowl-frog. In Corsican, a language akin to Italian, the word for tortoise, cupulatta, both echoes its shape and suggests its stomping gait. The dome shape is difficult for predators to get their jaws around. It does have a disadvantage, though, should the creatures when climbing tumble back on to it. All they can do is wave their legs helplessly in the air, trying to right themselves. Rescue can come only from some outsider tipping them over. An exception is the pancake tortoise. With its flat shell and unusual agility, it can flip itself over quickly when it lands on its back, a common occurrence when climbing in its natural East African habitats.

Made up of interlocking horny plates called scutes (Latin: scutum, shield), the shell stays the same shape as the tortoises increase in size. Of all the protective measures adopted within the animal kingdom, it is one of the surest. It is not an absolute protection, but it deters many predators. Indeed, a tortoisesshell is not unlike a soldiers helmet. The Roman historian Livy has Titus Quinctius addressing the Achaeans in 191 BC:

| Our defence is sure. Tortoises have survived for millions of years by operating undercover. |

like a tortoise, which I see to be secure against all attacks, when it has all its parts drawn up inside its shell, but when it sticks any part out of it has that member which is exposed weak and open to injury.

Like soldiers, too, tortoises are often camouflaged, the pattern of their shells blending in with their environment for extra safety. For example, the little Egyptian tortoise has a yellowish tan shell, whereas so-called Greek tortoises look more like brown earth. The under-shell, the plastron, is lighter in colour.

The young soft-shelled are still at risk, as were the giant tortoises on remote Indian and Pacific Ocean islands. Having no natural enemies before man, they could afford, in evolutionary terms to reduce considerably the bony part of their shells, which were not particularly hard. Nevertheless, they could be used as stepping-stones. It was claimed that on Galapagos they were so numerous that it was possible to walk quite long distances on their backs without touching the ground.

Hiding from predators, the pancake tortoise is one of the less visible creatures of East Africa.

When first discovered, the African pancake tortoise was thought to be underdeveloped and malformed. Its shell is flat, less than 4 centimetres high, and soft, yielding under pressure. An agile climber, it lives on rocky slopes in Kenya, Tanzania (including Serengeti National Park) and the