By the same author:

Freudian Slips

Why?: Answers to Everyday Scientific Questions

Why We Do the Things We Do

First published in Great Britain in 2016

by Michael OMara Books Limited

9 Lion Yard

Tremadoc Road

London SW4 7NQ

Copyright Joel Levy 2016

All rights reserved. You may not copy, store, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, recording of otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-1-78243-637-9 in hardback print format

ISBN: 978-1-78243-638-6 in ebook format

Illustrated by Greg Stevenson

www.mombooks.com

For Michelle, Isaac and Finn.

What is the best way to think about a problem? How should we approach the big questions about nature, morality and metaphysics? How do you come up with creative responses, challenge received notions, overcome prejudices and preconceptions? One way is to use the problem itself and frame it in such a way that it affords creative and insightful solutions, brings clarity in place of confusion and makes accessible the obscure. This is what experiments are for. In the modern era the term experiment implies a practical operation physically carried out in the real world, probably concerning science. But it can also have much a broader definition, encompassing a way of thinking that remains entirely intellectual and imaginary. Einstein called them Gedankenexperiment, or thought experiments, and in this book the term encompasses paradoxes and analogies: scenarios used to illustrate, test and tease out arguments and hypotheses, to make plain logical contradictions and push theories to breaking point.

Although they might sound like intellectual parlour games or curiosities, thought experiments are serious business. They have been the occasion for major reconstruction at the foundation of thought more than once in history according to American philosopher W. V. O. Quine, while the British philosopher Mark Sainsbury has written: Historically, they are associated with crises in thought and with revolutionary advances. To grapple with them is not merely to engage in an intellectual game, but is to come to grips with key issues.

Thought experiments have helped to shape every form of philosophy natural, moral and metaphysical midwifing the birth of concepts from infinity to relativity, from gravity to time travel, from free will to determinism, from uncertainty to reality. They can be destructive, helping to demolish theories and unfounded assumptions, to deconstruct dogmas and world systems. They can be illustrative, showing how a theory or argument can be plausible. They can be constructive, proving conclusions from premises, building mental models of possible worlds, fleshing out the implications of theories and findings.

Thought experiments are generally distinguished by offering concrete and often vivid imagery, portraying scenarios that range from the quotidian (an ass stood between two bales of hay; a man with a few hairs on his bald pate) to the bizarre (a sleeper awakes to find she has been surgically attached to a famous violinist; Achilles races a tortoise). They are frequently maddening, and often playful. For Einstein, this was the key to his Gedankenexperiment. He described them as consisting of psychical entities more or less clear images which can be reproduced and combined. It was this combinatory play of images that he identified as the essential feature in [my] productive thought.

This book offers its own combinatory play of images, from an arrow that travels without ever moving to a ship that stays the same despite being completely different, from demons, zombies and swampmen to colour-blind scientists, precognizant cops and non-existent cats.

The roots of science lie in natural philosophy (the study of the natural world), from the mathematics of motion to the mysteries of space and time. Thought experiments have proved to be powerful and essential tools in natural philosophy, helping to spark extraordinary bursts of creativity and profound insights into the nature of reality.

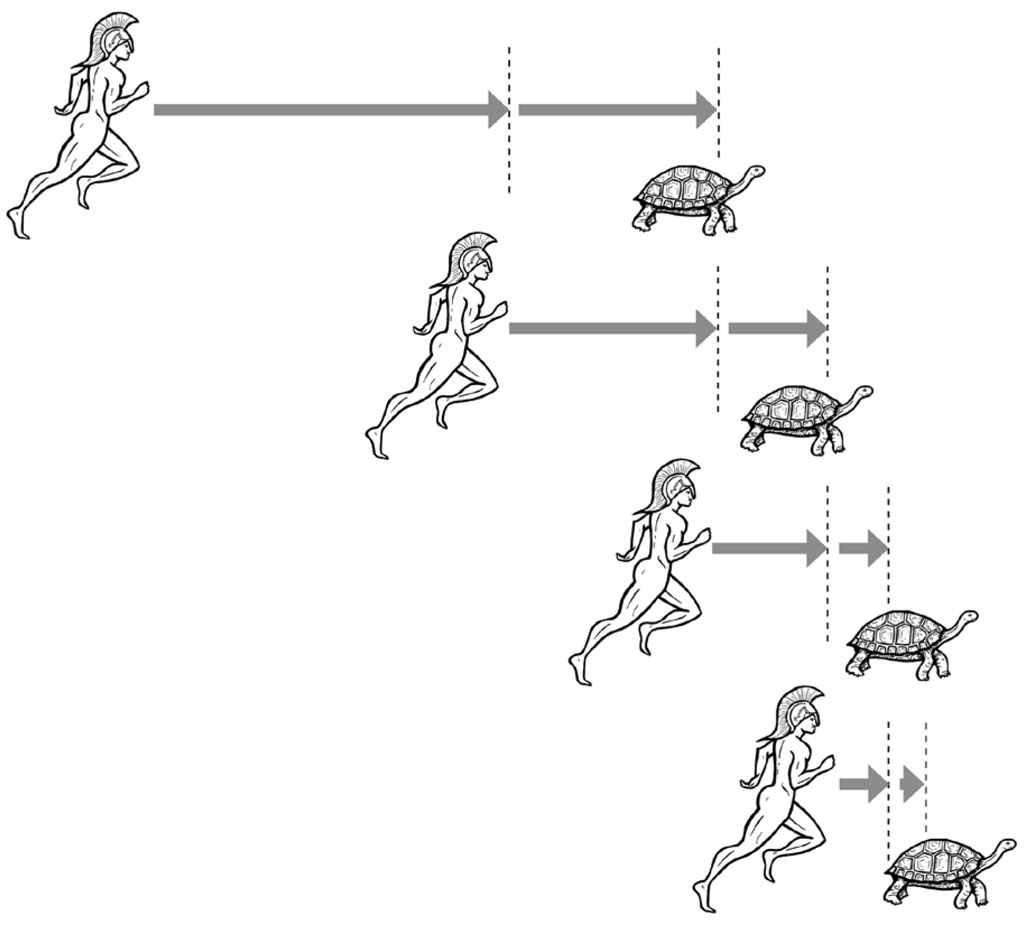

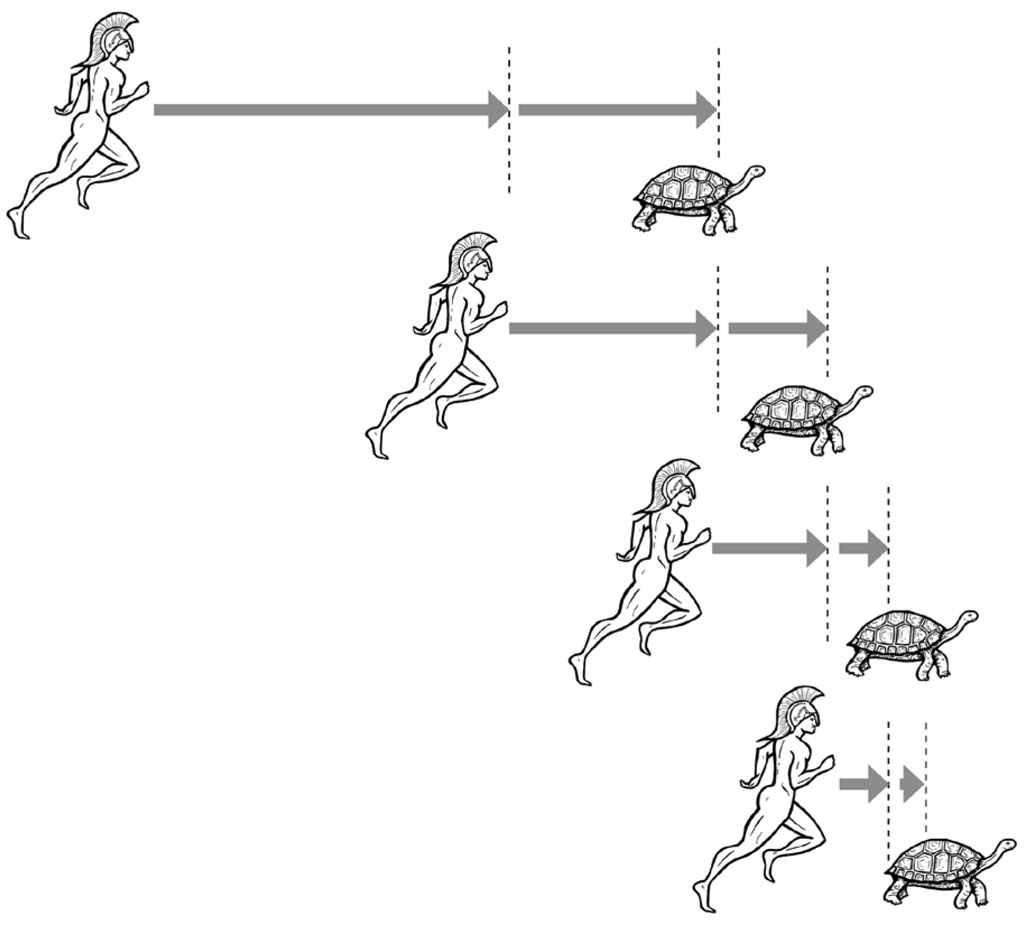

If the tortoise has a head start on Achilles in a race between the two, then by the time Achilles reaches where the tortoise was, it will have moved on; since Achilles has always first to reach where the tortoise was, he can never catch up with where it is now.

This paradox, which apparently proves that fleet-footed Achilles could never catch a ponderous tortoise, was one of many attributed to Zeno of Elea. Although little is known for certain of his life or work, the ancient Greek philosopher is thought to have lived and died in Elea, a Greek colony in southern Italy, between around 490425 bce. Zeno is said to have stated the paradox, popularly known by the title Achilles, in this fashion:

The slower when running will never be overtaken by the quicker; for that which is pursuing must first reach the point from which that which is fleeing started, so that the slower must necessarily always be some distance ahead.

The tortoise is always one step ahead.

Tiny steps

An elaboration of the paradox imagines a dialogue between Achilles and a tortoise, in which the ancient Greek hero laughs when challenged to a race by the cunning chelonian and readily agrees to allow it a 10-metre head start. Since their respective running speeds are 10 m/s and 1 m/s, Achilles calculates that he will overtake the tortoise in just over a second, wont he?

Not so, cries the tortoise, for given a head start I have you beaten. He goes on to explain why. After 1 second of running, Achilles will reach the 10-metre mark where the tortoise started, but by this point the tortoise will be at the 11-metre mark. It will take Achilles another 0.1 seconds to reach the 11-metre mark, but by this time the tortoise will have travelled another 0.1 metres. In the 0.01 seconds it takes Achilles to cover this distance, the tortoise will have gone a further 0.01 metres, and so on. Every time Achilles reaches the spot where the tortoise last was, the reptile will have moved infinitesimally further on. Flummoxed, the great warrior concedes defeat to his testudinal foe.

Being and change

This paradox was one of forty Zeno was said to have described in a book, although only a few survive and are known only through mentions in other peoples work. The paradoxes were probably intended to defend the theory proposed by Zenos mentor Parmenides, who had founded the Eleatic School, one of the leading philosophical studios of the ancient Greek world in the early fifth century bce. Parmenides argued for a philosophy of monism, claiming that all is one, and that all reality is a single, constant, unchanging, eternal Being. All appearance of change and variety in the universe is illusory; change and division would be forms of non-Being, and hence impossible.

Since motion is a form of change, Zeno devised several paradoxes to prove it impossible; the paradox of Achilles and the tortoise is one such. In fact, since Zenos original work does not survive, it is impossible to say for sure how he intended for them to be understood. One suggestion, for instance, is that they were actually parodies of over simplistic interpretations of Parmenides philosophies.

Next page