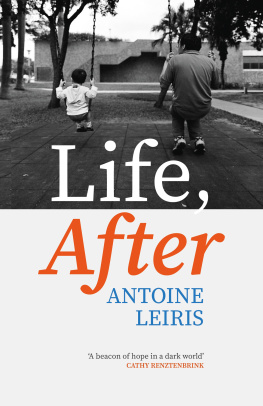

Also by Antoine Leiris

You Will Not Have My Hate

VINTAGE

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

New Zealand | India | South Africa

Vintage is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

First published by Harvill Secker in 2022

First published with the title La vie, aprs by

ditions Robert Laffont in France in 2019

Copyright Antoine Leiris 2019

English translation copyright Sam Taylor 2022

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Cover photograph Getty Images

Cover design Rosie Palmer

ISBN: 978-1-473-58375-7

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorized distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

We [] were, so to speak, the end of a lineage []. One might have thought that we didnt exist, that characters invisible but much more important than us were continuing to fill the mirrors of our house with their images. I would prefer to avoid even the suspicion of hyperbole, particularly at the end of a sentence, but one might say, in a way, that in old families, it is the living who seem to be shadows of the dead.

Marguerite Yourcenar, Alexis

Whoever wishes to remember must surrender to forgetfulness, to the risk of absolute oblivion and to that beautiful randomness which then becomes memory.

Maurice Blanchot, The Book to Come

Foreword

I wrote my first book during the strangest and most violent moment of my life. My wife, Hlne, had just been killed in the terrorist attacks at the Bataclan, on 13 November 2015.

In You Will Not Have My Hate, I described the days following her death, which I lived through with our son Melvil, who was seventeen months old at the time.

On several occasions since then, I have attempted to write again. At first, I tried fiction. I wanted to tell a story that wasnt mine, with invented characters and places. A real novel.

I spent months working on this, before resigning myself to the fact that it was beyond my capabilities. My imagination was wholly focused on the invention of our new life. I couldnt conceive of anything beyond that necessity: saving us, creating spaces where we could live, and inhabiting them. Existing.

I threw away all those pages and gave myself the time to live.

Grief is a succession of transformations. You slough off your old skins, one by one. You constantly change. This is what time does to everybody, in normal circumstances. But in this particular case, the changes happened more quickly.

Four years later, I can safely say that I am no longer the same man. The same is true for Melvil, of course. He isnt a baby any more, but a happy little boy.

During those years, he passed from silence and babbling to words and language. He has grown up so quickly.

I waited until we were on a solid footing before I started writing again. Then I tried to record those metamorphoses, the tides of change that have transformed us since our world vanished in a mist, up to the moment when almost suddenly the sky clears.

That is when it begins. Life, after.

So this book is not about ten days, but about four long years, during which I learned so much. I have tried to describe daily routines and special moments, to recount how I learned to become a father, to live with ghosts, to listen to them, and to accept this paper-thin gap between life and death.

Today, we are happy and free. Free of our past, and strengthened by our past.

Melvil and I have rediscovered meaning and pleasure in existence. So I wanted to write again, but nothing more than that. Just to write. In the first person.

About myself, Antoine Leiris: a son, a brother, a father. And about the strange and wonderful us that my son and I form together.

1

July 2016

It is the year after, in the middle of summer. I drop him at his grandmothers house so I wont have him under my feet. I kiss him the way I eat marshmallows unable to stop, stuffing myself until I feel sick.

I leave him, but I wish I could keep him close to me. Those marshmallow kisses lie heavy on my stomach.

In the first line, I wrote: the year after. Rereading this, I realise that my language has changed. Now, I say before or after, the way people talk about before or after the fall of the Berlin Wall, before or after the Second World War, before or after the invention of printing, before or after Jesus Christ. It is the tipping point of our story.

I never wrote: Hlnes death. I dont say it, and even writing it now feels wrong. I just vaguely locate periods of time by specifying before or after.

I understand how brutal and reductive this is. My way of avoiding the obstacle while recognising that its impossible.

So, it is the year after, in the middle of summer. Like a burglar, I have planned to act in silence and in darkness. No music, no light, nothing to enhance the moment.

At home, I wait until it is completely dark outside. I look through the window: dust falling onto the street below. A dense dampness starts to rise from the white-hot tarmac, like a body standing, stripping off, an arousing and afflicting body.

Its nearly time.

I open a bottle of Rully white wine has enough sulphites to allow me to forget the coming evening and sit on the floor with my glass.

I gave myself one night to attempt to do things right. To avoid the obstacle again.

But its obvious that Im lying to myself: it wont be enough. Ill have to be quick if I want to be finished by morning. Impossible to do it right with so little time. Impossible to do it right with so little desire.

I have to accomplish in a few hours what I have been putting off for months: to sort through all her things, to face up to the real shape of grief. The apartment feels like its flooded. With water, a continuous body of liquid, pouring through, filling the cracks, spreading over the surface.

Our apartment is intact; exactly as it was before. Nothing has moved since last year.

As teenagers, we would sometimes play this game: If you had to take three films to a desert island, which ones would you choose? A younger me would have said, without hesitation: 2001: A Space Odyssey, so that I could understand the final scene at last; The Verdict, because of Paul Newman; and Quai des Orfvres, so I could once again hear Louis Jouvets curt, husky voice.

Today, the question could be asked in different ways.

If you had to take three objects to remind you of that life, which ones would you choose?

If you had to take three objects so that your son would understand what that life was like, which ones would you choose?

Being an adult means thinking for Melvil as well as myself. Before, I was used to making important decisions only for myself, not for two people.

I wish someone could advise me, could tell me: in ten years, your son will be glad to possess that. In twenty, youll need this. In fifty, youll love looking at that object.

But I must act alone. And then I must accept responsibility for my choices.

I must stop the love of a whole lifetime at the moment when it broke. Then break it apart into images and instants. Categorise them and tidy them into little boxes, where they can live once again.