To my parents,

N ORM AND L IZ T RAVIS ,

who always got me the next book

And my grandparents,

H ENRY C LAY T RAVIS AND R ICHARD K. F OX ,

who gave me a name

I went to my first University of Tennessee football game at the age of six. It was the opener of the 1985 season, and it signified that my next-door neighbor Matt and I were finally old enough to be trusted with our dads in Neyland Stadium. I remember three things very well from this game:

- An older man behind us had an air horn, which he would set off every time a big play happened for UT. (Its too bad these are now banned, because, to a six-year-old, being able to push a button and double over every adult within sight was the height of first-grade accomplishment.)

- UT ended up with a tie score, 2626, on a late UCLA touchdown. The concept of a tie was particularly deflating to my six-year-old mind, because it was far more complicated than a win or a loss.

- Every time my dad, my next door neighbors dad Tim, and everyone else around us talked about the team they used the word we . As in, We cant seem to keep our feet underneath us, or We almost had a big play there. Around halftime I asked my dad why everyone was using the word we , which heretofore Id only heard applied when the speaker himself was actually involved in a pursuit. After all, I was not a team member and neither were any of the other men sitting in the lower-bowl end zone of Neyland Stadium. Because, said my dad, this means so much to most people here, they want to make themselves a part of it.

This adoption of the pronoun we troubled me for most of my first year of fandom. After that year, my trepidation quickly disappeared, and I became a member of the we college football family that echoes across the geographic regions of our country. My particular we was the University of Tennessee. My orange-colored tribal band so initiated, I have never looked back.

Now, Im a grown man with a home and a wife and a law degree. No one cards me at R-rated movies. If I wanted to, I could drive to the smutty gas station and load my trunk with pornography and beer. I even have a beard, a spotty and poorly maintained beard, but a beard nonetheless. To all who see me, I am indisputably an adult. However, some small part of me has never moved beyond the way I felt when I was in elementary school, watching University of Tennessee football games. I know Im not alone in this. Across the South, there are countless men and women just like me: People who face serious decisions at very important jobs, life-threatening illnesses, and bone-crushing stress yet, each weekend in the fall, revert to the rhythms of their preadolescent life. As the coming crispness of autumn reveals itself in the coolness of early mornings and late evenings, we all become, once more, eternally the children we no longer are.

Theres something about the pageantry and passionthe way sunshine comes later and departs earlier behind the colored leaves of the trees, and the pounding of drums in an onrushing band on a Southern campusthat stirs your heart. People who otherwise would not speak to you exchange high fives as you stand as one on a fall afternoon and scream in unison with blood-curdling fury. A feeling comes over you in these moments that is impossible to explain. Football time in the South has arrived.

One spring day, in the midst of an employment investigation designed to determine whether or not a coal mine pit boss had offered $19.75 to his fat coal mine secretary to give him a fully clothed, yet nonetheless lascivious, lap dance, it occurred to me that my life could be spent on more enjoyable endeavors. That, just maybe, there might be something more fun than interviewing people without teeth in an office filled with the fine, gray dust of disintegrated rock.

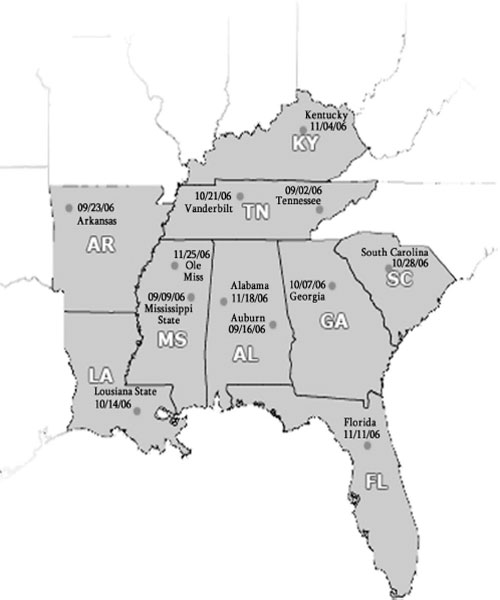

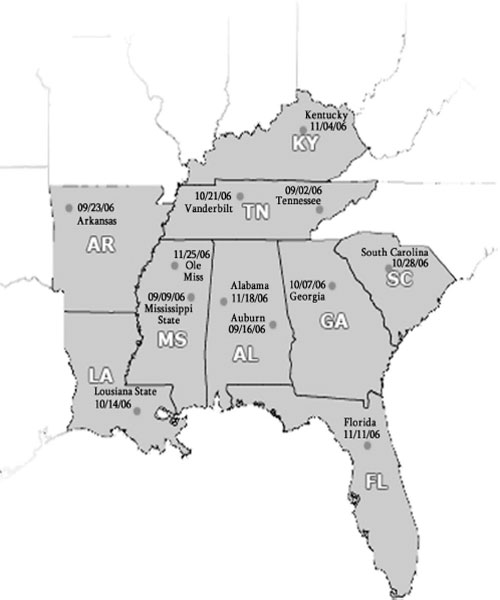

Thats when I had my first vision of the Dixieland Delight Tour. Instead of breathing gravel, I could spend a few months traveling around the Southeastern Conference, watching a football game in each of the twelve SEC stadiums. Fortunately, my column at CBS SportsLine offered the perfect platform to make my vision a reality. And, most importantly, I knew it would be fun. Amazingly fun. All my life Id wanted to be able to see a game from the stands of every SEC stadium. Even better would be to tour the circuit during a single season. So, I set about crafting a schedule that would allow me to travel to every SEC campus and attend a single game in each stadium. I branded the quest the ClayNation Dixieland Delight Tour;

The DDT schedule called for me to begin in Knoxville, Tennessee, on September 2 and finish in Atlanta, Georgia, for the SEC Championship on December 2. In between, Id have three months on the road to immerse myself in the game-day rituals and ironic excesses of the common fan. I was to become one with the rabid passion, the redneck braggadocio, and the cultural individuality of the South on football Saturdays.

It was to be a holy pilgrimage of sorts, a journey to all twelve Southern Meccas. From Nashville, Tennessee, to Columbia, South Carolina; from Lexington, Kentucky, to Gainesville, Florida; from Super Wal-Marts in Mississippi to the Bill Clinton Presidential Library in Arkansas to the riverboat gambling docks in Louisiana, the length and breadth of the South would be my home for the fall. And experiencing the Southeastern Conference as no one had ever done before would be my quest.

On doctors orders, my maternal grandfather, Richard Fox, was not allowed to watch University of Tennessee football games. That was because my grandfather, a former Tennessee player, watched the games with such ferocious intensity that his doctor was afraid he might have a heart attack. So, for most of my youth, at halftime of each Tennessee game, my grandfather would call my uncle and inquire as to the score. If UT was comfortably ahead, he would begin watching the taped game. If it was a close game, he would wait until the end of the game to find out the final score before watching. If UT lost, he would never watch the tape. At no time did I consider this to be abnormal.

My grandfather also blazed a trail for modern athletes by being one of the first University of Tennessee football players to leave school without a degree. In the early 1930s, he played for General Robert Neyland while living in a dorm beneath the football stadium. When I was older, and the two of us visited Knoxville, my grandfather pointed out where he had lived as a student under the looming steel supports. The windows of those rooms were filled with cardboard boxes, and it was unbelievable to me that my grandfather had ever been so young or that his grass-stained cleats had once hung outside the door. On that day, as I stood with my grandfather and gazed at the gridiron on which he had played, it seemed impossible that I could ever root for another football team. My bloodlines ran orange.

Only once in my life did my grandfather ever break his doctors orders and watch a live University of Tennessee game with me. It was in 1990, and I was eleven. It was the third Saturday in October. For University of Tennessee fans this meant one thing and one thing only: Alabama week. UT was heavily favored that year over a mediocre Alabama football team, and this was supposed to be the year that we would break Alabamas four-year winning streak over us.

On the day of the game, Grandpa bought me candy at a gas station outside Chattanooga whose sign had GO VOLS written alongside the gas prices. In so doing, he had chosen to drive past the gas station that had GO DAWGS written on its sign. That mans from Georgia, my grandfather said with evident disgust. Georgia was, after all, at least ten miles away from where we stood. Consequently, my grandfather never bought gas from that station and that Georgia Bulldog fan. In the South, you learn at a very young age that small geographic differences can be the deciding factor between friend and foe.