Praise for

Gatecrashing Paradise

Revealing aspects of a surprising little tropical nation wholly unknown to holidaymakers, Gatecrashing Paradise compares honourably with Arthur Grimbles A Pattern of Islands.

Alexander Frater, former chief travel correspondent of the Observer, author of The Balloon Factory, Tales from the Torrid Zone, Chasing the Monsoon and Beyond the Blue Horizon

Tom Chesshyre bravely and entertainingly exposes the dimensions of the Maldives that the tourist board is strangely shy of illuminating.

Simon Calder, Travel Editor of the Independent on Sunday

To Dexter and Florence

Gatecrashing Paradise

Misadventures in the Real Maldives

Tom Chesshyre

First published by

Nicholas Brealey Publishing in 2015

|

|---|

| |

|---|

Carmelite House | Hachette Book Group |

50 Victoria Embankment | 53 State Street |

London EC4Y ODZ | Boston, MA 02109, USA |

Tel: 020 3122 6000 | Tel: (617) 523-3801 |

www.nicholasbrealey.com

www.tomchesshyre.co.uk

@tchesshyre

Tom Chesshyre 2015

The right of Tom Chesshyre to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

ISBN: 978-1-85788-627-6

eISBN: 978-1-47364-467-0

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

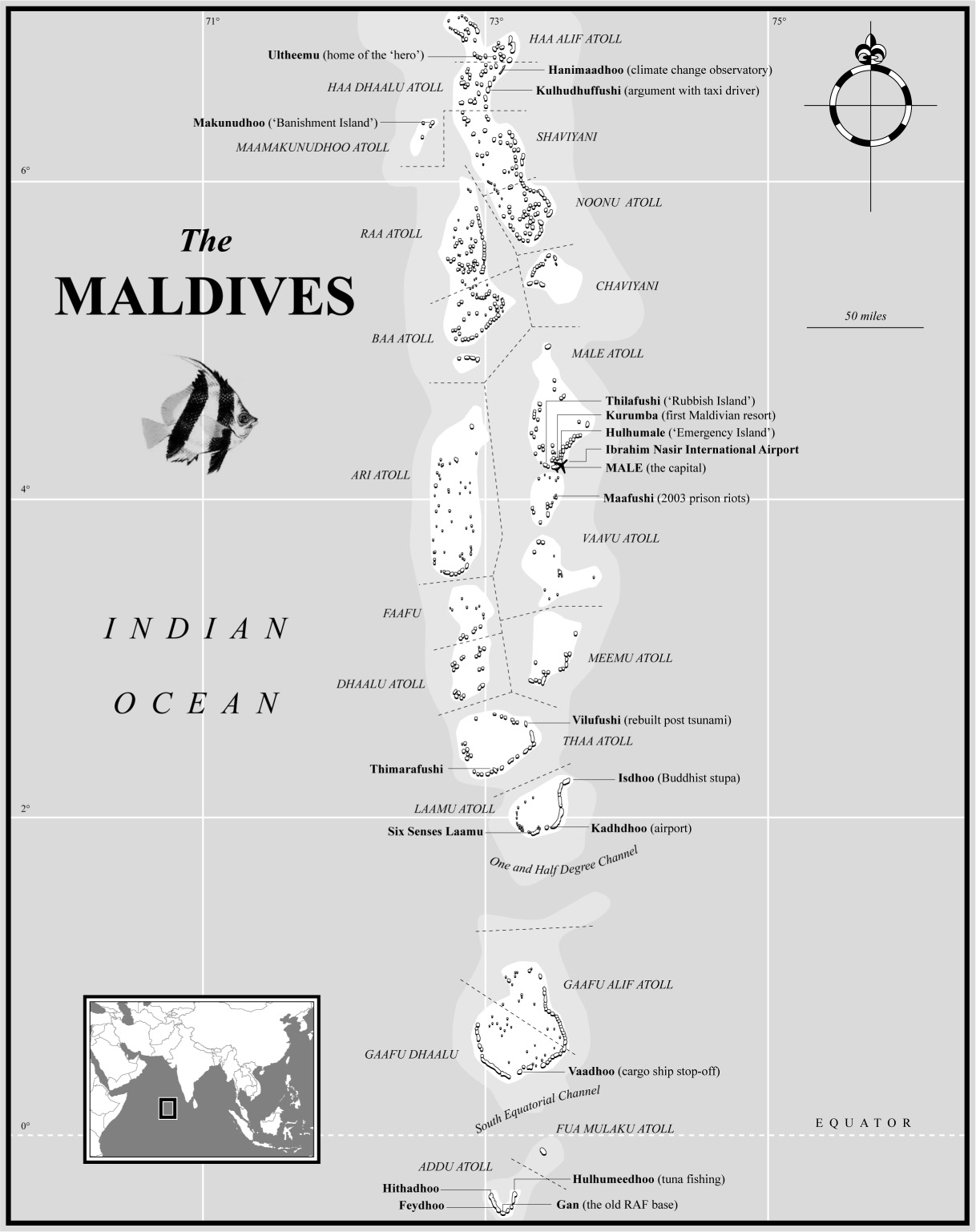

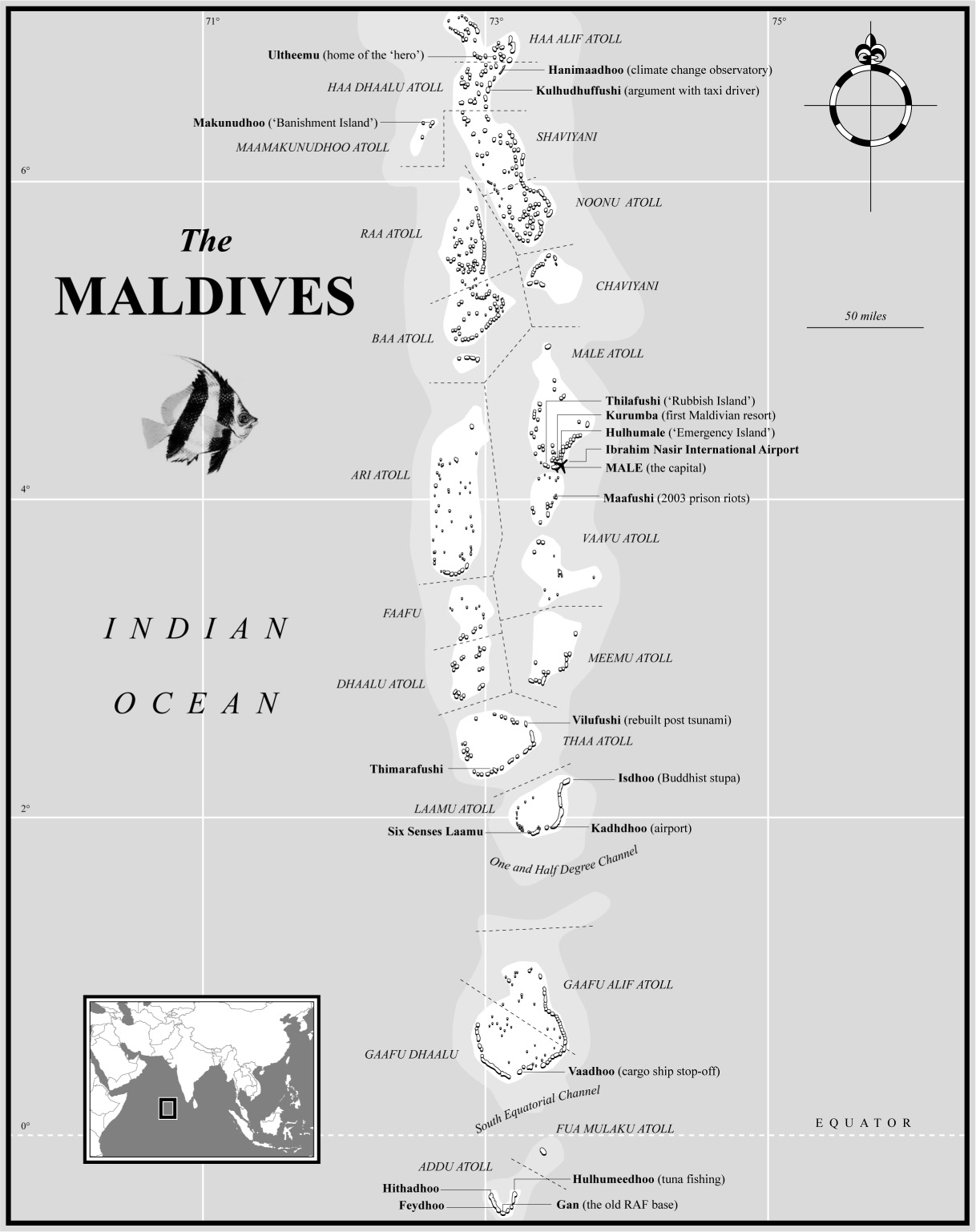

Maps by Matthew Swift

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording and/or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publishers. This book may not be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise disposed of by way of trade in any form, binding or cover other than that in which it is published, without the prior consent of the publishers.

Printed in the UK by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

Contents

Preface

Our whole mindset regarding going abroad has altered beyond recognition in the last few years. I began as a journalist on the travel desk of the The Times, hoping to see the world, inspired by writers such as Paul Theroux, P J. ORourke, Jonathan Raban, Eric Newby, Bruce Chatwin, Jan Morris, Dervla Murphy, Norman Lewis and Bill Bryson. Heading out with a notebook to explore backwaters, meet unusual characters, experience the sights, sounds and smells of distant climes travel journalism was a romantic notion. Apart from travel literature, guidebooks, radio broadcasts, newspapers, films and television documentaries (presented by the likes of Alan Whicker and Michael Palin), there was no other way to learn about distant shores. Travel was expensive and knowledge was unreliable; guidebooks soon became out of date.

In the years between the late 1990s, when I was starting out, and now, I continued with travel writing despite a growing feeling that the internet, as it developed and boomed, could tell you almost anything you needed to know before you took off from Heathrow or caught a train through the Channel Tunnel. Reporters were increasingly becoming tied to their desks. Newshounds found themselves attached to screens that flashed wire stories and, more recently, tweets. But as a travel writer, by definition, you had to get out and about, see things with your own eyes.

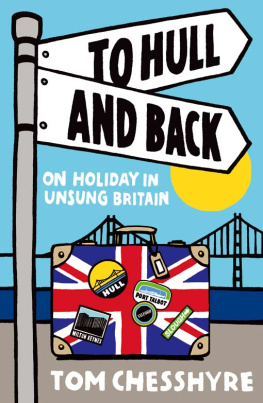

After taking several journeys to unpronounceable places on low-cost airlines 1p flights, I wrote a travel book entitled To Hull and Back, describing some of the least likely places to spend time off in the UK. This was a reaction to taking so many easyJet flights; I wanted to stay on the ground. It was also in the spirit of Alain de Bottons engaging book The Art of Travel, in which the Swiss-British philosopher ruminates on finding the extraordinary in the ordinary.

With the internet so pervasive and travel becoming almost ludicrously easy, I liked the idea of slowing down and taking a closer look at places that were less trodden. I stayed on the ground once more to see Europe by high-speed train (Tales from the Fast Trains) before visiting Tunisia, Libya and Egypt a year after the Arab Spring (A Tourist in the Arab Spring). News of the uprisings, which some were comparing to the fall of the Berlin Wall, was coming thick and fast on television and over the internet. But I wanted to see it for myself, rather than relying on information that flashes up on a screen.

Some people suggest that the (apparent) omniscience of the World Wide Web makes travel writing redundant. It is a dying genre, the doom merchants say, as everything is out there already: every corner of the earth covered and accessible at the click of a computer mouse. There can be no Wilfred Thesiger-style journeys through the Empty Quarter of Arabia, no quixotic rambles through the Hindu Kush la Newby, no Bruce Chatwinesque immersions in African nomadic tribal life. And perhaps thats true. The surprise element no longer exists when you can read about most places on your smartphone.

Most places, but not all. And in the Maldives, I wanted to take a different approach. Before I went, I had little idea what islands I would visit and what I would come across. I had no grand plans mapped out on the internet, no instant information to show me the way, no World Wide Web at my fingertips. Escaping a Google world by ditching my smartphone and laptop, I had little alternative to following my nose and letting instinct lead the way.

I had some rare time off work, annual leave that had somehow stacked up: a honeymoon period of sorts, an unexpected break from daily life. And there was a certain irony to this. I was heading to one of the globes most renowned honeymoon hotspots the Maldives on my own: my girlfriend and I had split in the weeks before I decided to go. We had been together a while and it felt like a turning point, a spring clean moment of anything being possible. I was stepping off the treadmill of the ordinary. Goodbye commuting. Goodbye deadlines. Goodbye to everything connected to worries. Hello sunshine. Hello sea. Hello to discovering a distant country from the ground up, without monitors bleeping messages I really did not want to read.

Thats why I bought a ticket to the Indian Ocean.

We heard the boom of breakers from miles offshore as they crashed upon the reef. It was a sound new to our ears, a note of majesty once heard, forever remembered.

Arthur Grimble, A Pattern of Islands

The first guests at the Brisas del Mar arrived in some style in a chauffeur-driven Isotta-Frashini at the end of May, providing instant and final confirmation of the villagers belief that all outsiders were basically irrational, when not actually mad.

Norman Lewis, Voices of the Old Sea

Later I realized how foolish it had been to have any scruples, for big hotels are quite merciless towards their employees.

George Orwell, Down and Out in Paris and London

When the rate of return on capitalism exceeds the rate of growth of output and income, as it did in the nineteenth century and seems likely to do again in the twenty-first, capitalism automatically generates arbitrary and unsustainable inequalities that radically undermine the meritocratic values on which democratic societies are based.

Next page