For Janet

Copyright 2000 by Dave Bidini

Cloth edition published in 2000

First paperback edition published in 2001

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system, without the prior written consent of the publisher - or, in case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency - is an infringement of the copyright law.

National Library of Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data

Bidini, Dave

Tropic of hockey: my search for the game in unlikely places

eISBN: 978-1-55199-674-5

I. Title.

GV 847. B 52 2000 796.962 C 00-931678-7

We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program for our publishing activities. We further acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council for our publishing program.

McClelland.& Stewart Ltd.

The Canadian Publishers

75 Sherbourne Street

Toronto, Ontario

M 5 A 2 P 9

www.mcclelland.com

v3.1

Hockey is a road that you follow.

Jane Siberry

I t was 1986, just outside Athens, Georgia, when hockey found me. After an uneventful pilgrimage to the home of REM - rock n rolls best band that year - my friend Tim Vesely and I left town in the falling blue-black of the Southern night. Soon the engine of our Olds was labouring across the sloping countryside, rattling and wheezing like a dog pulling on a leash. So, we turned off at the first exit and clanged into the nearest town, Clarksville.

We rolled into the town square, switched the engine off, and sat there clinging to that universal untruth: Maybe it just needs to cool down a little. We waited, fired the engine, but there was neither a prrrr, nor a clank.

It was a gorgeous night. Soft. Warm. Insects sang. A police cruiser approached in our rear-view and pulled in behind us. I had visions of Cracker troopers and the Jackson County jail. We climbed out of our car and he climbed out of his. To my relief, he looked nothing like Warren Oates.

He spoke first. So what are you guys doing in Clarksville in the middle of a Sunday night in a broken-down Olds with Ontario plates? There was the long answer, of course, but we gave him the short one. And then he said:

Well, theres no garage open now. Youd best wait until morning to get this looked at.

What about hotels? we asked.

Motels. Theres Harveys place up the road. Lets see if old Harvs still awake.

We rode in the cruiser to the motel. It felt pretty cool getting to ride in the back seat of a Georgian copmobile without first having to bludgeon someone to death. We sat behind the steel mesh partition and watched the dark countryside roll past. The cop made small talk. He seemed like a decent fellow.

At the motel, we followed him to an open door that leaked the blue, winking light of a television. The cop called in, Harv? Harv? You up? An old man in his pyjamas came to the door. Got a breakdown here, the cop told him. Kids need a room until they can get their car fixed.

All right, said Harv, rubbing his eyes. The office. And we followed him.

Harv was a tall fellow with a dented face and ravaged skin.

Wherere you boys from? he asked, in a voice like falling rocks.

Toronto, said Tim.

Toronto? he echoed, scratching his head.

You know it? I asked.

Know it? Christ, Im from Oshawa.

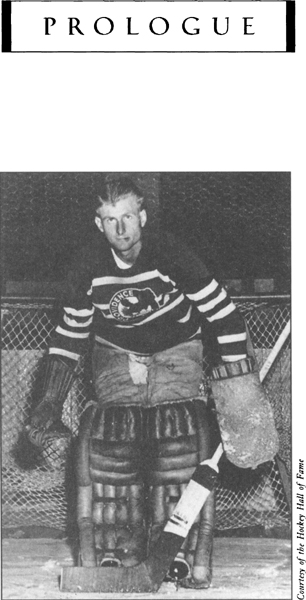

It was then that I noticed the pictures on the office walls: goalie pictures. The wood panelling was covered with them, old photographs of Harvey standing in the net, his face young and smooth, his head topped with bristle-brush hair. He was wearing black pads and gloves that looked like oven mitts. An unvarnished stick was angled against his skates, which were old and wrinkled and leathery, a white number painted on the ankles. Underneath the glass countertop on which Harv had opened the motels registry, there were two hockey cards: Harvey Bennett, Junior, Philadelphia Flyers, and Curt Bennett, Atlanta Flames.

Who are they? I asked.

Two of my boys. Both of them in the National Hockey League.

Born in 1925 in Edington, Saskatchewan, Harvey had been a career minor-leaguer who was called up from the Boston Olympics to fill in during the wartime player shortage. His only big-league year was in 1944-45 with the Boston Bruins, when he played twenty-five games and went ten wins, twelve losses, two ties (4.20 goals-against average). Harveys footnote to the story of hockey was that he was in the net on the night Rocket Richard scored his fiftieth goal. His profile in Total Hockey shows that he played for the Regina Abbotts, Providence Reds, Chatham Maroons, Trois-Rivires Lions and Washington Presidents, long-extinct teams. I imagined backwater rinks and cold bus rides. I could see every game carved into his face.

Didnt wear masks then, said Harv, pointing to an old photo of himself.

That must have been tough, I said.

Tough? I took shots here, here, here, and here, he said, poking his face.

Do you still watch hockey? I asked.

No. Not since the Flames left Atlanta. You know, a lot of people were sad when they took them away. Youd be surprised. Therere good hockey fans down here. They were just starting to get to know the game, before they went

Up to Calgary.

Ya. Calgary.

The old goalie took our names and gave us a room where moths studded the walls like thumb-tacks. We turned on the TV and there was Dave Thomas of SCTV being interviewed by David Letterman. We turned off the lights, feeling like wed been weirdly embraced by Canada. The next day, Harvey called a tow truck and drove us to the garage. He talked to the mechanic, who fixed our transmission and sent us home. Harvey was our guardian angel in pads and gloves, a messenger from beyond. It wasnt until we hit the open road that I realized how unlikely it had been to find this spectral figure from Canadas game in such a faraway place. And as the snow started to fall across Ohio, grew thick over Niagara County, and turned into a blizzard once we reached home, I hoped that one day I would look back and understand.

The first thing I did when I got back to Toronto was to start playing hockey. I figured it was the least I could do to acknowledge the hockey gods. I hadnt played competitively since Id turned my back on the game as a teenager but, after asking around, I found a Sunday night skate of musicians in McCormick Arena in downtown Toronto. McCormick is nestled on a side street in a neighbourhood thats relatively sleepy, but every now and then, some stoner tire-irons a car and makes off with his weight in Thundermug and Neil Diamond cassettes, which shows you what crack will do to the mind. I played there once a week, struggling to find strength in my legs and learning how to shoot, and I got better with each game. Before I knew it, Id fallen in love with hockey all over again.