For my teammates, here and there.

Sleep

This much we know: the night before Game Eight, Dryden went to bed early. I imagine him fast asleep in his pyjamas, laid flat against a hard, unforgiving Soviet pillow and paper napkin sheets too small for the tall goalie, but his rest was probably more fitful than that: glove hand thrashing and legs kicking at phantom pucks shot into the darkness of his dream. Dryden was down but the rest of the team wasnt, because how could you sleep knowing that when you woke up it would be to face the terrible cackling skeleton of sporting fate staring back at you in a cold mirror of a white hotel room in a strange city on the other side of the world? Thats why, when Ted Blackman, the Montreal sports broadcaster, returned to the Hotel Intourist around 11 p.m. after walking the streets of Moscow in the soft late autumn of September 27, he found Team Canada coach Harry Sinden moving through the lobby, his mind soaked in fear and uncertainty, swinging from hope to hopelessness, winning to losing, hero to goat, and back again. Harry unstuffed his hands from his dark blue Team Canada blazer, rubbed his forehead, and appealed to Blackman, Do me a favour, Ted. Go into the bar and see if any of the players are there. Its past curfew and I dont want to be the bad guy tonight, telling them to go to bed. Blackman said sure, turning towards the tall padded doors of the hotels lounge. Moments later, he came out. Whats the report? asked Harry. Anyone in there?

Harry, said Ted, trying not to laugh. If you could get Dryden out of bed, you could have a team meeting.

War

In the afternoon, they brought us into the gym: hundreds of children, terrified and hopeful in the stale air. I was eight years old in 1972. Canada playing Russia in hockey was unusual in itself, but watching Canada play Russia in hockey on TV in the afternoon was stranger still. A friend, Mark Mattson, said, Back in those days, the only things you watched on TV in class were sex education films or religious movies.

So watching hockey, this was really weird.

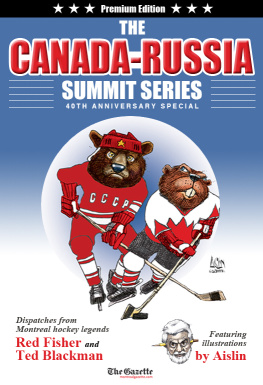

Before the start of the game, my phys ed teacher track-panted in an age when only athletic instructors wore that sort of thing barked for us to Sit Down! and Keep Quiet! when all we wanted to do was run around and play tag or war as a way of easing the thick unbearable tension. We played war because the 72 series was war, or at least thats what Espo said. We were told that the Russian players the Soviets were trained as soldiers, too, and studied closely, you could see this in the way their play seemed born from a strategic operative zone to zone to zone, a chalkboard diagram come alive. We were also told that the players lived on a military camp a basa where their athletic corporals allegedly warned them that if they missed a break-out pass or gave away the puck, they would be sent to Siberia, which is where I found myself forty years later, sitting in a kitchen drinking tea and eating dark chocolate with women who lived through such times. It was hard, yes, said one of them, reapplying her lipstick every few minutes, but we were happy, too, in a way. There was fear of what might happen, but there was also a great feeling of togetherness. I asked her, But with the gulags right here... didnt that make it hard for you to believe in the hope of the future? Overhearing my question, one of the womens husbands took me into the living room, where he pulled out an old map and went region by region, showing me how strong and mighty the Soviet Union used to be. Yes. We were in awe of you; afraid, too, I told him. Then the mans son showed up. But Dad, he said, back then if your boss treated you badly, there was nothing you could do. If you spoke out, you would be fired, and sometimes, worse. The father rolled his eyes and looked at me. They fought for awhile as I sat on the sofa thinking about a question Espo had once asked, then answered, himself, Would I have killed to win the series? Yes, I believe I would have. In September 1972, we ignored the gym teachers cries and kept playing war. Then Mr. Dawson screamed one final time. Children, THE GAME! Its starting! We looked up.

Gretzky

In 2004, I was travelling through Tatarstan with a fiftysomething Soviet broadcast employee: a cameraman and sound engineer named Sergei. Whenever an unmarked car would come up behind us, hed stroke his Van Dyke beard and tell us, Look: KGB. Once, after we were stopped by police on our way back to Kazan, he added, This is how they take you. Quietly, out of nowhere. It wasnt until Id suffered three days of this that I realized he was joking. I played along for his amusement until, one time, our driver noticed a different set of lights in the rearview mirror. He shouted at us to stay quiet. The car pulled up beside ours, and two men spoke to the driver. After discovering that we were from Canada, they asked if any of us were Wayne Gretzky. It was Sergeis turn to laugh. We drove on.

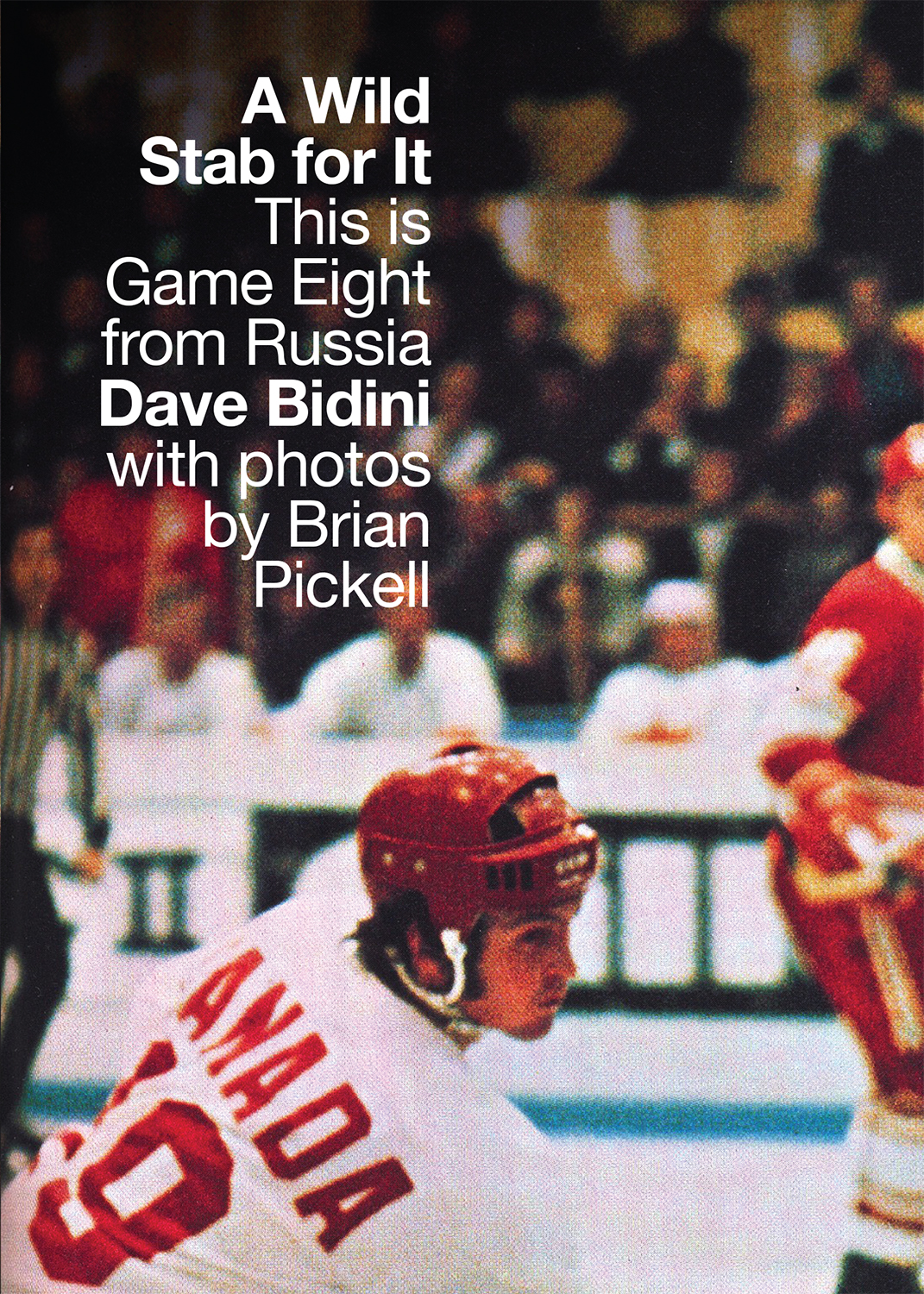

Head Cold

First, there was a shot of an empty ice surface. The transmission came and went, suggesting a fat, jumpsuited technician hitting an enormous metal box with a stick in some studio in Agincourt, trying to bring the pictures back. The shot held for a moment, as if stillness might have somehow calmed the trembling, anxious viewer. Then, there was a voice part cartoon frog, part leprechaun, part Popeye and part head cold wobbling like old tape. It was Foster Hewitt, Tonight we are making hockey history. I wouldnt miss this one for all the tea in China. Then the camera moved slowly, showing the great players marching head down and in two single files along the carpet to the rink. Generally, the Canadians seemed hairier and rounder, and, generally, the Russians were smaller and blonder, although both teams wore red and white or white and red and had, generally, a look of duty about them as they stepped onto the soft ice. There was no pumped-up glove-slapping go-get-em histrionics while skating out of a flaming logo; no small children holding team flags with a song by U2 filling the arena from speakers dangling around the circumference of the rink; no grrrrring announcer rolling his rs as he introduced the teams (home team loudest; visitors, less so). Instead, the scene was darkly meditative: a quiet (for now) building and two dozen players whose look suggested one more long walk down the weird carpet to the too-warm ice surface, and one more speech from the coach before one more long, draining game in this long, draining series. If the event had forced players on both teams closer to the hot sight at the centre of their nations gaze weaving them into the fabric of cultural and political history on the barbed needle of sport it also made them question, near the end of the series, who they were skating for and why. Revisionist poetics tell us that Team Canada wanted to win for Johnny Frozen Pond and Uncle Albert back in Adenoid and the writers of the thousands of letters sent to Russia by Canada Post which team assistants used to wallpaper the corridors outside the dressing room but, more than that, the players wanted to win the series for themselves. Ken Dryden told me, I knew about Ralph Branca and Bobby Thompson and what had happened to the Brooklyn Dodgers. I knew there would be a goat, and I didnt want to be him. Only a few players could sense the weight of what might happen to their reputations if Canada lost to Russia, but everyone knew that it would be bad. As for the Soviets, theyd been to Montreal; theyd been to Toronto; theyd been to British Columbia. No man could stay the same after doing what millions of their countrymen had only dreamed.