ALSO BY DAVE BIDINI

On a Cold Road, 1998

Tropic of Hockey, 2000

Copyright 2004 by Dave Bidini

Cloth edition published 2004

Trade paperback edition published 2005

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system, without the prior written consent of the publisher or, in case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency is an infringement of the copyright law.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Bidini, Dave

Baseballissimo : my summer in the Italian minor leagues / Dave Bidini.

eISBN: 978-1-55199-676-9

1. Baseball Italy Nettuno. 2. Bidini, Dave Travel Italy Nettuno. I. Title.

GV863.51.N472B43 2004 796.357094562 C2003-902055-X

We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program and that of the Government of Ontario through the Ontario Media Development Corporations Ontario Book Initiative. We further acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council for our publishing program.

McClelland & Stewart Ltd.

The Canadian Publishers

75 Sherbourne Street,

Toronto, Ontario

M5A 2P9

www.mcclelland.com

v3.1

For C. Abel

Listen up, because Ive got nothing to say

and Im only going to say it once.

Yogi Berra

CONTENTS

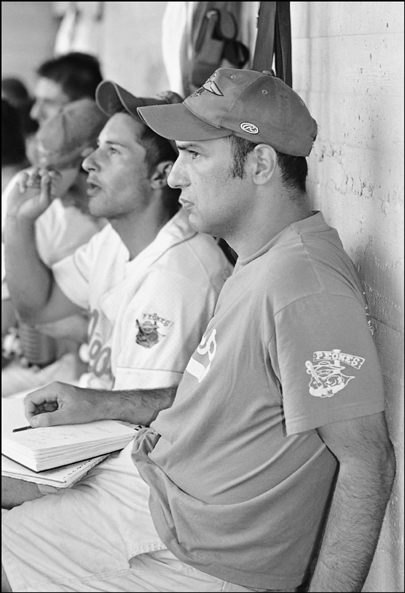

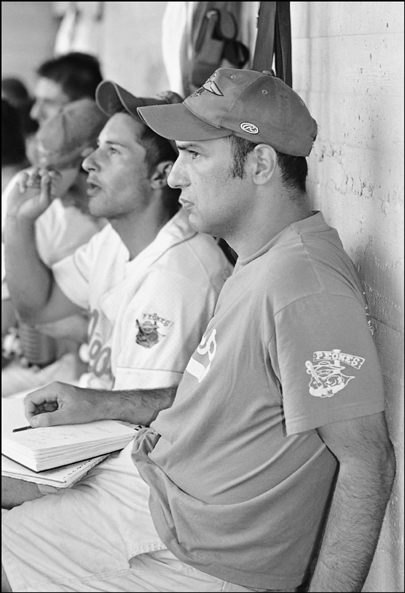

NETTUNO PEONES, 2002

First base: The Emperor

Second base: Mario Mazza

Shortstop: Skunk Bravo

Third base: Chicca

Catchers: The Big Emilio, Paolo Danna

Right field: The Red Tiger

Centre field: Mario Simone, Solid Gold

Left field: Fab Julie, the Natural

Infield: Christian, Mirko, Fabio from Milan

Pitchers: Cobra, Chencho, Pompozzi, Pit the Stricken

Manager: Pietro Monaco

S TRONZO WITH A S MITING P OLE

D uring a pre-game workout in Nettuno, Italy, Mirko Rocchetti, an infielder with the Peones, arrived at the park carrying a tray of cornetti, brioche, and biscotti. Simone Cancelli (the Natural) followed twenty minutes later with a large box, which he placed on the ledge of the dugout. He lifted the lid, pulled back a layer of crepe paper, and revealed a small mountain of fresh croissants, their light, flaky shells embossed with vanilla crema. A few minutes later Francesco Pompo Pompozzi, the Peones twenty-one-year-old fireballer, produced two green bottles filled with sugar-soaked espresso, and passed out little white plastic cups. Ricky Viccaro (Solid Gold) who looked, as always, as if he were standing in front of a wind machine showed up a half-hour into the game, swinging a red Thermos of espresso, which he cracked in the fifth inning and refilled for the beginning of the second game. Someone else placed boxes of sweets on racks above the bench, and they were polished off in no time.

This sugar fiesta was typical for the Peones, Nettunos Serie B baseball team. They believed as did many Italians that sugar and coffee were all you needed to get you through any game. Andrea Cancelli (the Emperor) munched on energy pills that tasted like tiny soap cakes. At a game in Sardinia, I saw Fabio Giolitti (Fab Julie) pat his rumbling stomach before fetching a box of wafer cookies from his kit bag, which he passed out, two at a time, to his teammates. Then Mirko asked me, Davide? Are you hungry? and promptly handed me two panini spread with grape jelly the Italian athletes equivalent of an energy bar. At the same game, Mario Mazza, the Peones second baseman, gathered the team excitedly, as if hed just cracked the opposing teams sequence of signs, only to pass out packets of sugar hed swiped from a caf. The players poured them down the hatch. I joined in, even though I wasnt playing, just watching the Peones, the team Id come to Italy to write about.

I found language as much a cultural divide as the approach to food, though I was able to find my place among the Peones by spouting a combination Italo-Canadian-Baseballese, at the risk of becoming Team Stooge. At times, I wondered whether the boys were asking me questions just to see how I would mangle their mother tongue.

One day, Chencho Navacci, the teams left-handed reliever, heard me comment that a hit had been il pollo morto.

Tuo pollo? he asked.

No, la palla. La palla il pollo. Il pollo morto.

Okay, okay, he said, smiling.

You know, dying quail, I said, reverting to English.

?

The chicken is dead, I said, making a high, curving motion with my hand. The ball la palla. La palla il pollo.

Il pollo?

I couldnt understand why Chencho was so confused. Id always assumed that dying quail baseballs term for a hit that bloops between the infield and the outfield was one of those universal baseball terms.

Si! Il pollo morto! I repeated.

Il pollo morto? Okay, is good! he said, turning away.

Later, I told Janet, my wife, what had happened at the ballpark.

La qualia, she corrected. You should have said la qualia.

How was I supposed to know they had quail in Italy?

What did you think? They have chicken, dont they?

Ya, but quail.

Yes, quail. And I dont think pollo is the right word for chicken. La gallina is how you say chicken. Pollo is what you order in a restaurant.

Pollo is restaurant chicken? I said, mortified.

I think so.

So, you mean I was telling Chencho that the ball was like a piece of cooked chicken?

Yes, Im afraid you were.

Flying cooked chicken?

For my first few weeks with the team, I probably sounded like a moron. I regularly confused the word for last with first, and used always instead of never, as in Speaking good Italian is always the first thing I learn. Id also fallen into the embarrassing habit of pronouncing the word penne (the pasta) as if it were pene, the Italian word for penis. But I was excused for saying things like Id like my penis with tomatoes and mushroom, and, to their credit, the team and townsfolk hung with me. After a while, the players must have noticed a pattern in the things I said at practice: dying quail, rabbit ball, hot potato, ducks on the pond, bring the gas, in his kitchen. They probably figured I was just really hungry.

Before leaving Canada for Italy in the spring of 2002, I bound my five bats together with black packing tape. They looked like a wooden bouquet and their heads clacked as I laid them on the airports baggage belt: the brown, thirty-four-ounce Harold Baines Adirondack, two new fungo bats, a red Louisville smiting pole, and a vintage Pudge Fisk hurt stick, with Pudges signature burnt into the fat of the wood.

My bats and I werent alone. There was also my wife, Janet; our two children, Cecilia, a curly-haired two-year-old blabberpuss, and Lorenzo, not ten weeks old; and for the first part of the trip Janets mother, Norma.