An

Unreasonable

Woman

An

Unreasonable

Woman

A True Story of

Shrimpers, Politicos, Polluters,

and the Fight for

Seadrift, Texas

Diane Wilson

Foreword by

Kenny Ausubel

CHELSEA GREEN PUBLISHING COMPANY

WHITE RIVER JUNCTION, VERMONT

Copyright 2005 Diane Wilson. All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be transmitted or reproduced in any form by any means without permission in writing from the publisher.

Managing Editor: Marcy Brant

Copy Editor: Robin Catalano

Proofreader: Eric Raetz

Designer: Peter Holm, Sterling Hill Productions

Design Assistant: Daria Hoak, Sterling Hill Productions

Printed in the United States on recycled paper.

First printing, July 2005

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2

Chelsea Green sees publishing as a tool for cultural change and ecological stewardship. We strive to align our book manufacturing practices with our editorial mission, and to reduce the impact of our business enterprise on the environment. We print our books and catalogs on chlorine-free recycled paper, using soy-based inks, whenever possible. Chelsea Green is a member of the Green Press Initiative (www.greenpressinitiative.org), a nonprofit coalition of publishers, manufacturers, and authors working to protect the worlds endangered forests and conserve natural resources.

An Unreasonable Woman was printed at Sheridan Books on New Leaf Eco 60 Warm White, a 60 percent post-consumer waste recycled paper.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wilson, Diane, 1948

An unreasonable woman : a true story of shrimpers, politicos, polluters, and the fight for Seadrift, Texas / Diane Wilson.

p. cm.

eBook ISBN: 978-1-603580-41-0

1. Wilson, Diane, 1948- 2. Shrimpers (Persons)United StatesBiography. 3. Chemical plantsWaste disposalEnvironmental aspectsTexasSeadrift. 4. Environmental protectionTexasSeadriftCitizen participation. 5. EnvironmentalismTexasSeadrift. I. Title.

SH20.W55A3 2005

639'.58'092dc22

2005009894

Chelsea Green Publishing Company

P.O. Box 428

White River Junction, VT 05001

(800) 639-4099

www.chelseagreen.com

For Wayne, Molly, and Kenny

And the sweet, sweet water underneath my skiff

Contents

W hen the first-draft manuscript of An Unreasonable Woman arrived in the mail from Diane Wilson, I had already resolved, sight unseen, to option her story for development into a dramatic film. Her larger-than-life heroines journey had all the makings of an electrifying Hollywood thriller. Visions of Erin Brockovich, Silkwood, ChinaSyndrome, and The Perfect Storm danced before my eyes. It would be hard to make up a more dramatic and colorful mythic tale of archetypal heroism than Dianes true story of her epic battle to stop the massive pollution of her beloved Texas Gulf Coast by Formosa Plastics and other giant chemical corporations.

All of us, worldwide, now contain industrial chemicals in our bodies unknown to our grandparents. A National Geographic advertisement by the American Plastics Council in 2000 celebrated plastic as the sixth basic food group. In fact, Americans now ingest an average of 5.8 milligrams a day of DEHP, a phthalate plasticizer used in everything from food wrappings to childrens toys, medical devices, and ubiquitous PVC products. DEHP is an endocrine disrupter, a gender bender whose adverse health effects are evident at parts per trillion. Such estrogen-mimicking chemicals are associated with early puberty in girls, some as young as one year old. In infants and children, they produce measurable neurological deficits and changes in temperament, including laughing and smiling less, feeling more fearful, and becoming agitated under stress. As Dr. Theo Colborn has said, these chemicals can change the very character of human societies.

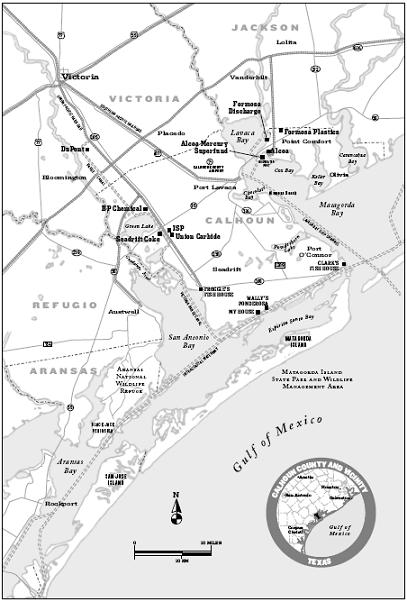

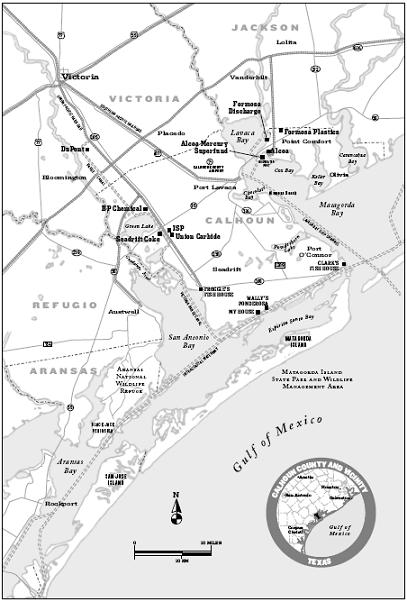

The Texas Gulf Coast is one of the richest and most diverse ecosystems in the world. The regions biggest manufacturer of PVC (polyvinyl chloride) is Formosa Plastics, a multi-billion-dollar global octopus that has systematically been plasticizing Lavaca Bay. PVC is one of the most toxic and noxious substances in the organochlorine family of chlorine-based industrial poisons. The international treaty on persistent organic pollutants recently banned these chemicals, and members of the European Union are phasing out their use. Its easy to see how Formosa got its reputation as a poster child for villainous corporations. This leader of Taiwans petrochemical industry had environmental practices and safety violations so appalling that twenty thousand Taiwanese came out under threat of police violence to protest its proposed new $8 billion complex. Thats how Formosa ended up in Texas.

Texas and Louisiana regularly vie for which can lead the nation as the most toxic state, and Texas was willing to give Formosa $200 million in subsidies to retain a shot at the title. When Formosa announced its plans for a $1.3 billion expansion of a plant making the raw materials for PVC, it got the customary red-carpet treatment and chamber-of-commerce confetti parade for creating jobs in an economically depressed region.

All that changed when Diane learned of an EPA report that rated Dianes little Calhoun County (population fifteen thousand) as the most toxic in the nation. Diane wondered if that might help explain the mass dolphin die-offs and alligators floating belly up on her beloved Lavaca Bay. And why the commercial fishing was dying off as well. She decided to ask some questions, and started holding meetings.

With only a high school education (and a dislike of chemistry) Diane taught herself to file successful legal briefs and decipher mountains of scientific and technical EPA records. Her knowledge of Formosa became so intimate that the companys own lawyers routinely called her for information about their operation. After exhausting all other means, she resorted to nonviolent civil disobedience and direct action, ultimately leading her to a daring and likely fatal showdown on Lavaca Bay.

I knew Dianes story because she had spoken at the 1997 annual Bioneers Conference, which I founded. We were doing a special program that year on water, from the myriad environmental threats against water to the hopeful raft of solutions that bioneersbiological pioneers working with nature to heal naturewere applying to cleaning up, conserving, and protecting the worlds imperiled waters.

Following talks by an impressive array of accomplished scientists and social innovators, Diane began to speak. She exuded authenticity and sincerity. She described how, as a mother of five and former head of the PTA, she came to challenge some of the largest and most powerful chemical corporations in the world. Growing up, Diane said, the bay was like her grandmother; she spent endless hours in private conversation with her. She took the destruction of the bay very personally. Call it family values.

Once Diane started turning over some political rocks, just about everyone in the tiny company town, who depended on the chemical plants for their livelihood, warned her to back off. She did not. Along the way she realized that when a system is so profoundly corrupt, sometimes upholding the law means breaking the law. The rest is history, or, in this case, her story.

Diane recounted her jaw-dropping tale in the plainspoken eloquence of South Texas. The audience was transfixed. She received a standing ovation. Being unnaturally shy, she practically ran off the stage.

A year later I tried to reach Diane to invite her back to speak at Bioneers, but she seemed to have fallen off the map. Then, two years later, I got a call from her out of the blue. I immediately invited her back to Bioneers, but soon discovered her reason for calling: she had written a book and wanted to know if I would mind looking at it. Like many writers, she was bashful and self-deprecating. Of course I wanted to see the book! I felt as if I were already watching the movie.