About the Authors

Cathy A. Small is professor emerita of anthropology at Northern Arizona University and a resident of Flagstaff, Arizona, where she enjoys life with Phyllis, her spouse of thirty years. A dedicated practitioner and teacher of Buddhist meditation, she offers talks, classes, and retreats to community members and inmates at the county jail.

Jason Kordosky is a researcher for the Culinary Union, where he helps workers fight for fair wages, job security, health insurance, pensions, and safe working conditions. He works and lives in Las Vegas, Nevada, with his spouse, Magally, and his best cat friend, Tobie. He enjoys hiking, photography, and writing poetry in his free time.

Ross Moore is a proud disabled Vietnam veteran and resident of northern Arizona. After surviving three decades of recurrent homelessness, he now lives with his wife, Wendi, in a HUD-subsidized apartment. His citizen rights have been restored after he lost them in his twenties following felony convictions for burglary. He is an avid collector of vinyl records.

Copyright 2020 by Cathy A. Small

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. Visit our website at cornellpress.cornell.edu.

Permission to reprint the quotation from Thich Nhat Han from The Heart of Understanding: Commentaries on the Prajnaparamita Heart Sutra (20th anniversary edition) , Parallax Press, United Buddhist Church 2009, first published in 1988 that appears in chapter 2, has been granted by Parallax Press.

The authors express their deep thanks to Do Mi Stauber for her expert indexing of this book.

First published 2020 by Cornell University Press

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Small, Cathy, author. | Kordosky, Jason, author. | Moore, Ross (Homeless person), author.

Title: The man in the dog park : coming up close to homelessness / Cathy A. Small ; with Jason Kordosky and Ross Moore.

Description: Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019038321 (print) | LCCN 2019038322 (ebook) | ISBN 9781501748783 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781501748790 (epub) | ISBN 9781501748806 (pdf)

Subjects: LCSH: Homeless personsUnited States. | HomelessnessUnited States.

Classification: LCC HV4505 .S64 2020 (print) | LCC HV4505 (ebook) | DDC 362.5/920973dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019038321

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019038322

Preface

In Buddhist thought, compassion ( karuna ) is described as the quivering of the heart in relation to the suffering of others; it is accompanied by an impulse to relieve the suffering witnessed. Compassion is considered a natural human response, but it arises only when the walls of othernessborn of fear or disdain, greed or judgmentare not set in stone to block it.

This is why there is something to be said about the purposeful effort to step outside of your own reality. (Or is it actually to allow other realities, other lives, into your own?) When I have truly done this in my own lifemoving into a village on a South Pacific island, taking a year off as a professor to live as a freshman in an undergraduate college dorm, or finding an authentic friendship with a homeless manthe results have been life-altering and, often, life-giving too. I think this is because such experiences upend our sense of what is true; they open us to the fine details of realms that others inhabit, stretching the boundaries of our insight and also our compassion.

This was not where I found myself more than a decade ago when I first met Ross Moore, a homeless man in a dog park. I am very aware and not very proud of how I first reacted, with profound distrust and fear. But I am just part of a culture. I would have to be a more remarkable person than I am to have acted otherwise.

More than ten years later, it is easier to see who he is and what I am, too, because the two are related. Every other world I have entered has offered me a window into my own, at the same time as it immersed me in other lives that came to touch me deeply enough to alter my perspectives, sometimes even my path.

I suppose this is why I, and Jason Kordosky, a coauthor, both became anthropologists, although our anthropology is as much a perspective of intimacy and nonjudgment as a profession. The fruits of this perspective have been profound and far-reaching for us both. Like others who cross cultures or the boundaries of our upbringing, we find in ourselves not only a greater responsiveness to the human condition but also the delight of living in a world less alien, less hostile, less unloving than it felt before.

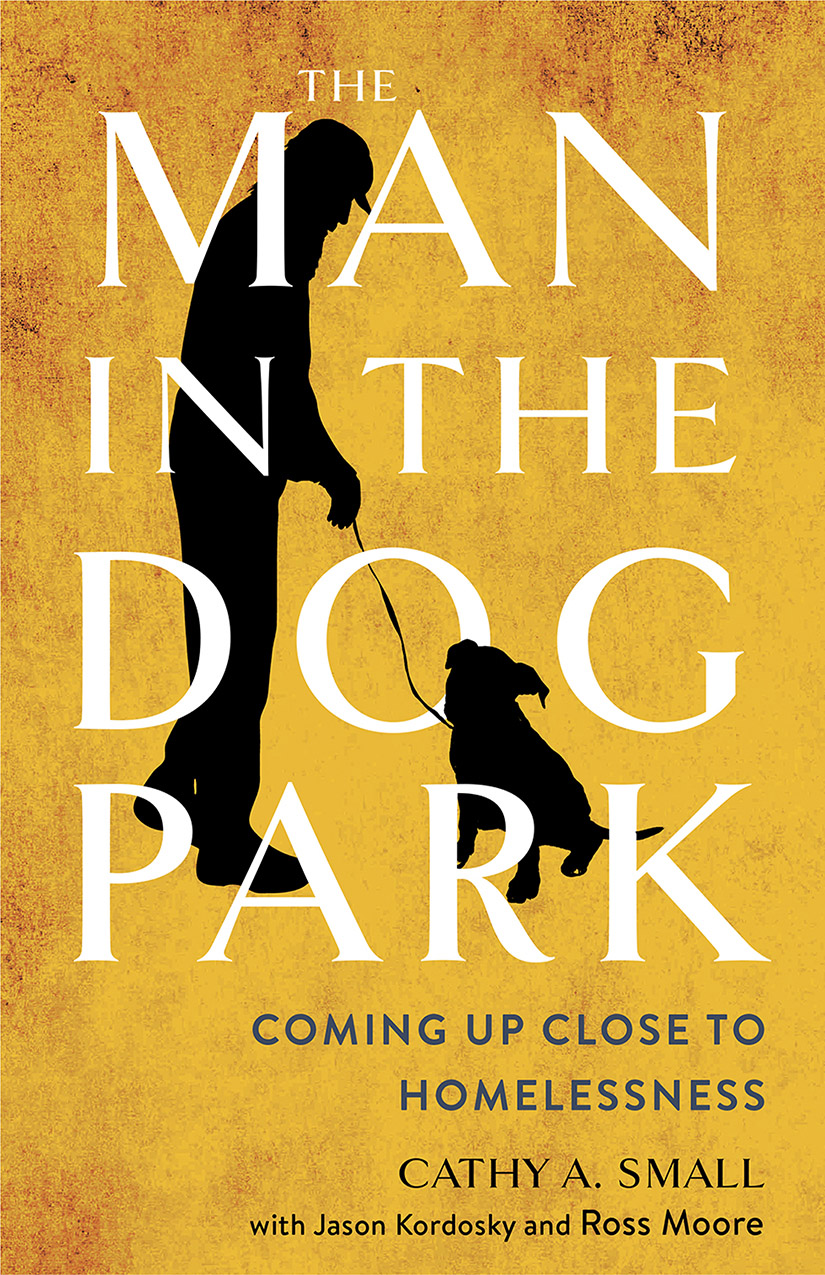

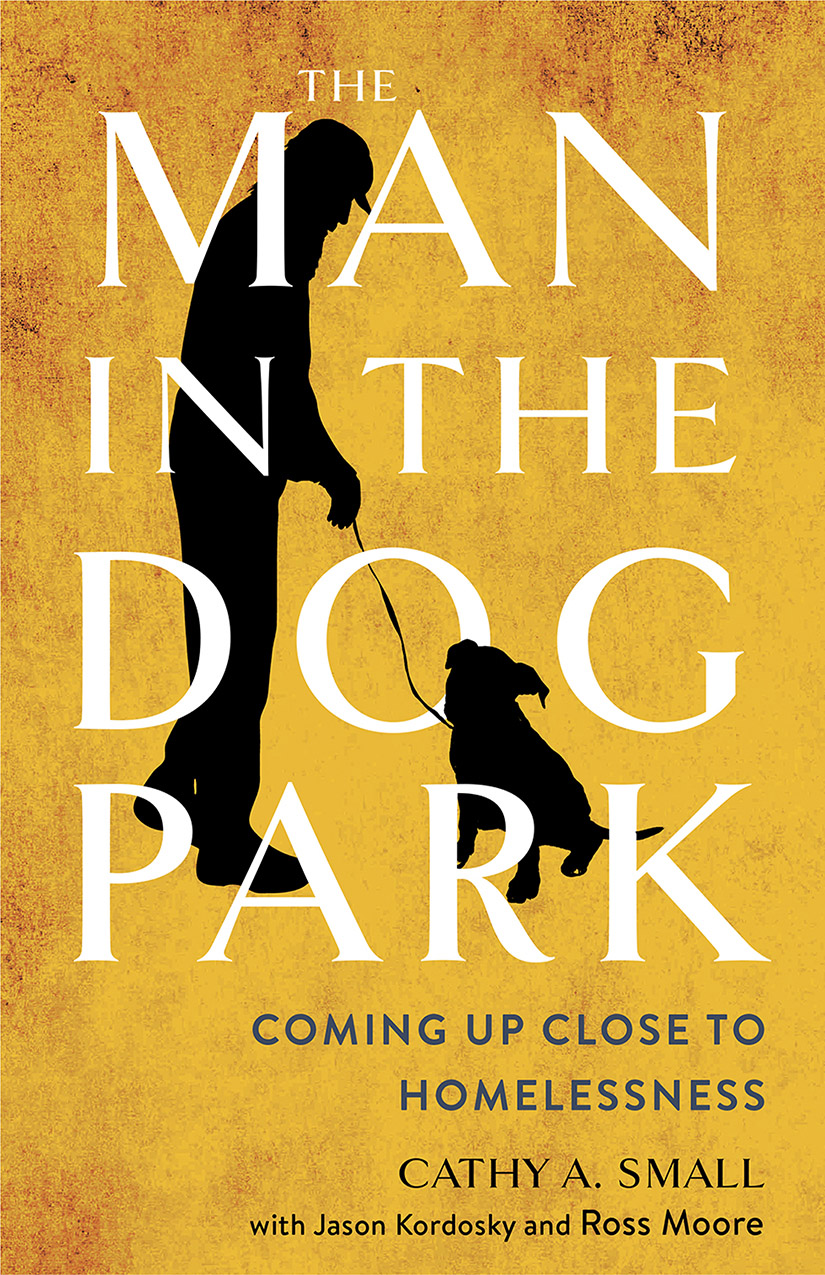

The cover image invokes the man in the dog park whom I first saw as a homeless figure with a capital H and all the adjectives and sentiments, reactions and baggage, that come with that. So, lets begin there, with our own stereotypes. It is where I began too.

1

The Beginning

It was 2008, we think. Ross doesnt remember the details of the very first time we met, but I do. I had entered the dog park early, as I do every morning with my three dogs. It must have been getting toward winter, because the park just before 7 am was not yet fully light, and I was aware of the man already seated on a bench inside the park. I had not seen him before. He was in his fifties, with a solid build and a very full, thick graying beard. His army green jacket seemed soiled, and he kept his eyes lowered as I entered. I looked quickly around to see that he had come with a dog, and indeed a mixed chow was sniffing in the distance within the enclosed, treed, block-long rectangle that serves as a municipal dog park. I felt a bit more at ease seeing the dog, but still, I remember making sure, in my old New York way, that I was always closer to the one entrance gate than this other figure in the park.

My fear and discomfort then embarrass me a decade later, now that Ross, the man in the park, has become a friend. It is not that my city radar was fully off-kilter. Ross lived in the woods with his dog; he was also a former felon. Its just that, like any of our labels, these do not really tell us much of true importance.

At the park, there were many more mornings when Ross and I observed each other before exchanging more than nods. I remember noticing how well Ross cared for his dog, and how much his dog cared for him. Regulars at the dog park quickly become its citizens, sometimes its nosy neighbors. Who cleans up and who doesnt. Whose dogs are not controlled. Who fills the empty dog bowls with fresh water. Ross was just plain and simple a good citizen and, for me, even a hero. When, one morning, I became unwittingly embedded in a dogfight with five or more snarling, snipping dogs, it was Ross who came running to save me from an errant dog bite.

We exchanged first names, and then some superficial details of our lives, much later deeper words and addresses. Ross lived in the woods outside city limits, because sleeping inside the limits invited the police. He worked, on and off, at different jobs. He was, at points, a day laborer, taking sundry construction jobs. A trucking repair garage hired him after he performed well on a multiple day labor stint, but then the recession... and he was among the first to be laid off. At the time I had begun to know him better, he was working as a painterhired onto a work crew for a multi-home project at the east end of town. When the project ended, so did his job. That was often how it went. Working and not working, with an occasional paycheck going toward a couple of nights at a motel, but mostly storing away some cash for food on the non-working days.