Rachel Carson (19071964) was one of the most influential American nature writers of the twentieth century. She wrote four critically acclaimed books, as well as articles and pamphlets on conservation and natural resources. Grounded in the scientific discoveries of the day, Carsons works were notable for their intimate lyric prose that appealed to everyday Americans. She is considered one of the first environmentalists and popularized new ideas and words to describe mans relationship to the earth, such as ecology, food chain, biosphere, and ecosystem.

Born in the rural town of Springdale, Pennsylvania, near the Allegheny River, Carson spent much of her childhood roaming her familys sixty-five-acre farm and exploring the woods around her home. Her lifelong love of nature, encouraged by her mother, was coupled with a passion for writing, and her first published piece appeared in the popular childrens publication St. Nicholas when she was ten years old.

Carson pursued writing at the Pennsylvania College for Women (now called Chatham University) but switched her focus to biology before graduating in 1925. After studying at the esteemed Woods Hole Marine Biological Laboratory in Massachusetts and receiving a masters degree in zoology from Johns Hopkins University in 1932, Carson joined the U.S. Bureau of Fish and Wildlife Service, where she worked for fifteen years as a scientist, editor, and editor-in-chief of the bureaus publications. When she was named junior aquatic biologist in 1936, she was one of only two female professionals at the bureau.

Carson began writing natural history articles for the Baltimore Sun and other papers during the Depression and was encouraged to transform her scientific articles and pamphlets into general-interest pieces. In 1941 she published her first book, Under the Sea-Wind, which tells the story of the sea creatures and birds that dwell in and along North Americas eastern coast. In 1951 she published The Sea Around Usabout the ecosystems within and surrounding the worlds oceanswhich captured the imaginations of readers around the world. The book became a cultural phenomenon and was named an outstanding book of the year by the New York Times, won a National Book Award and John Burroughs Award, and inspired an Academy Awardwinning documentary of the same name. The book has sold more than one million copies and has been translated into twenty-eight languages. With this success, Carson left the Fish and Wildlife Service to become a fulltime writer, and in 1955 she published a follow-up to her bestseller, called The Edge of the Sea.

A year after publishing The Edge of the Sea, Carson adopted the orphaned son of one of her nieces. Stories of her outdoor adventures with Roger would become the touchstones of her essay in Womans Home Companion magazine, Help Your Child to Wonder, which was published posthumously as the illustrated The Sense of Wonder (1965).

But it was Carsons fourth book, Silent Spring (1962), that would again catapult her into the limelight. In this book Carson challenged the widespread, conventional use of many chemical pesticides, including DDT, citing the long-term effects on marine and animal life. Silent Spring provoked an outcry of concern, as well as criticism from the chemical industry, government, and media. However, shortly after publication, her findings were accepted by the Science Advisory Committee under President John F. Kennedy. In 1970 President Nixon established the Environmental Protection Agency, and two years later the use of DDT was banned. The publication of Silent Spring has been credited with sparking the environmental movement in the United States and continues to inspire readers today.

Rachel Carson died in 1965 from breast cancer. She was fifty-seven years old. In 1969 the Fish and Wildlife Service named the Rachel Carson National Wildlife Refuge, near Carsons home in Maine, in her honor.

Rachel Carson as a young girl. She said that one of her earliest childhood memories was of her love for books and reading. (Image: Carson Archives.)

Carson with her pet dog. She described herself as a solitary girl, who was always happiest with wild birds and creatures as companions. (Image: Carson Archives.)

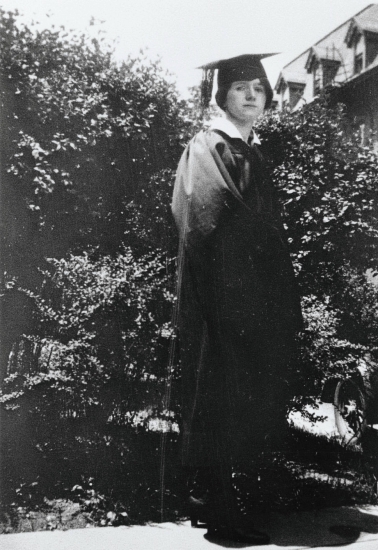

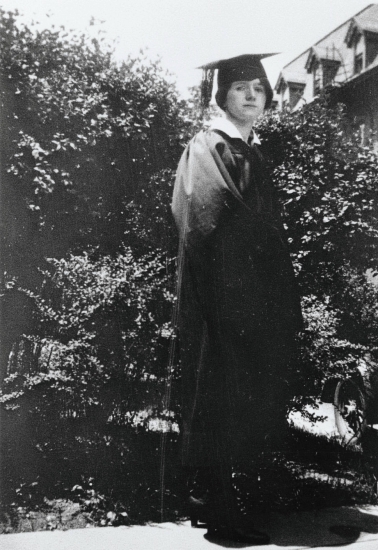

By the time she graduated high school, Carson had become known for her meticulousness and intelligence. (Image: Carson Archives.)

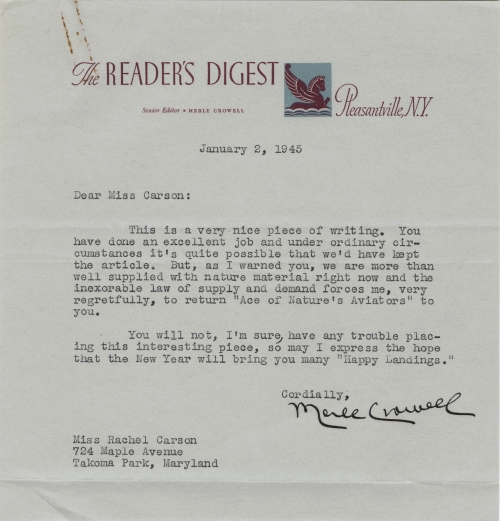

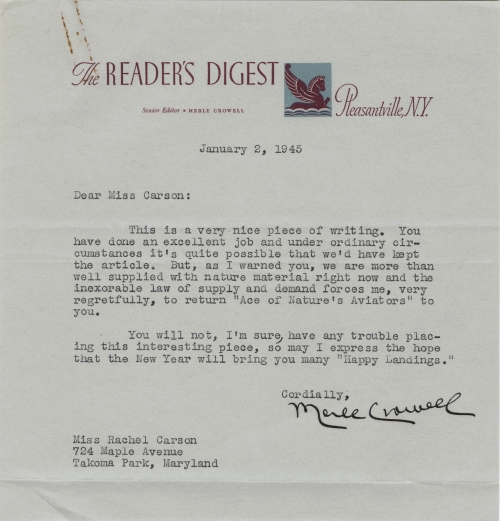

A letter from the senior editor of Readers Digest declining an article Carson had written titled Ace of Natures Aviators, which advocated for rehabilitating the common starling bird. The letter, dated January 2, 1945, commended the piece and lamented the magazines lack of space in which to print it. She sold a condensed version of the article to Coronet in 1945 while she was in need of money following an emergency appendectomy. (Image: Carson Archives.)

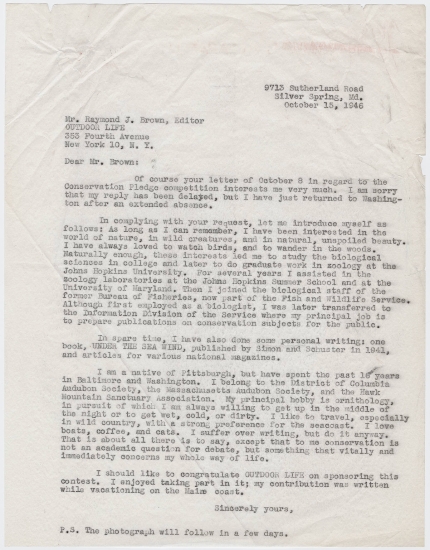

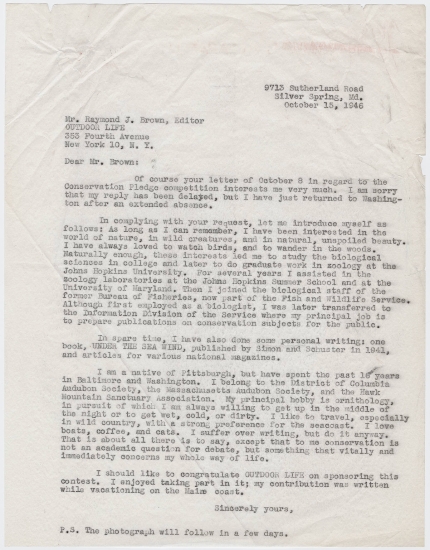

A letter from Carson to Raymond J. Brown, editor of Outdoor Life, written in 1946 after she was named a finalist in the magazines writing competition. In the letter, Carson declares that conservation is not an academic question for debate, but something that vitally and immediately concerns my whole way of life. (Image: Carson Archives.)

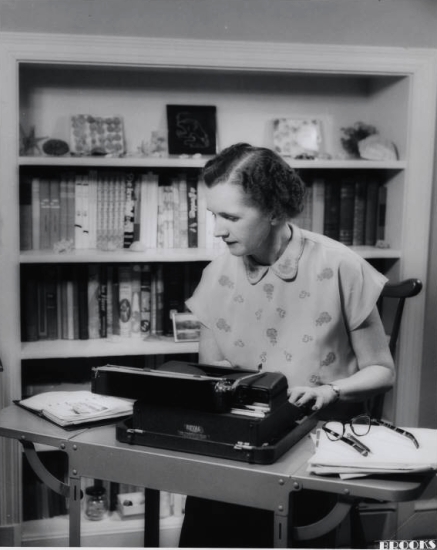

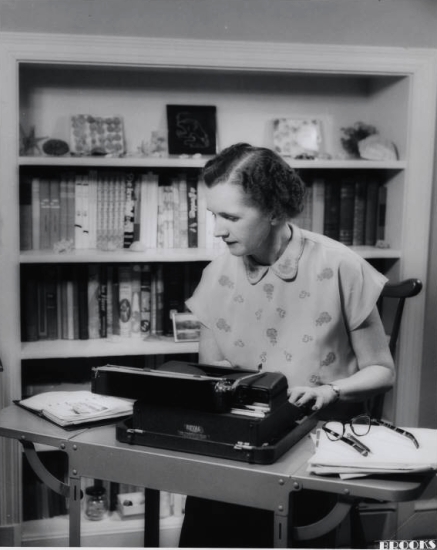

Carson at her typewriter. She brought together a rare passion for writing with a detailed understanding of science. (Image: Brooks.)

Carson writing on a dock. She expressed her love for nature first as a writer and later as a student of marine biology. (Image: Edwin Gray.)

Carson later in her life. Her message of living in harmony with the natural world still resonates today. (Image: Carson Archives.)

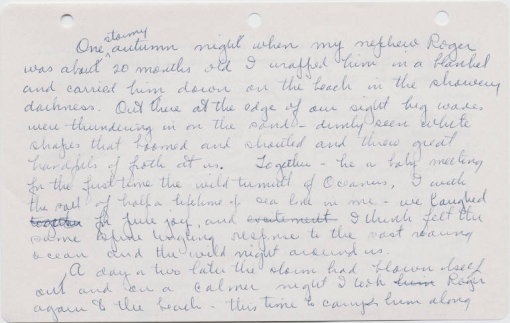

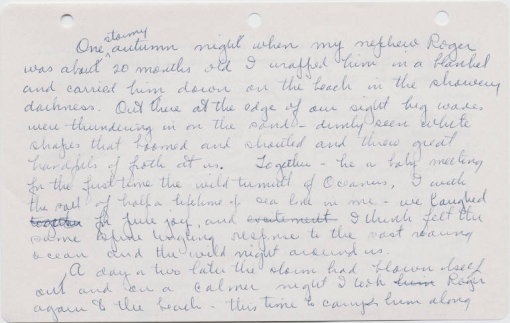

A handwritten manuscript page from an early draft of The Sense of Wonder, which was published posthumously in 1965. (Image: Carson Archives.)

Images courtesy of Rachel Carson Papers, Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

Under the Sea Wind

Rachel L. Carson

To my Mother

Contents

While the sun and the rain live, these shall be;

Till a last winds breath upon all these blowing

Next page