Contents

FISH WRAPPED

True Confessions From Newsrooms Past

ESSENTIAL ANTHOLOGIES SERIES 13

Guernica Editions Inc. acknowledges the support of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council. The Ontario Arts Council is an agency of the Government of Ontario. We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada.

FISH WRAPPED

True Confessions From Newsrooms Past

COMPILED AND EDITED BY

David Sherman

TORONTO CHICAGO BUFFALO LANCASTER (U.K.)

2020

Copyright 2020, David Sherman, the Contributors and Guernica Editions Inc. All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication, reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise stored in a retrieval system, without the prior consent of the publisher is an infringement of the copyright law.

Michael Mirolla, general editor

David Sherman, editor

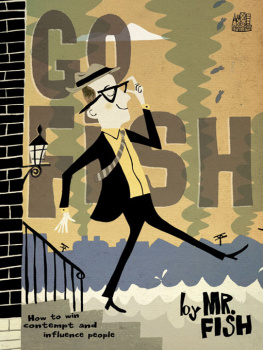

Cover illustration: Aislin

Cover design: Mary Hughson

Interior Design: Rafael Chimicatti

Guernica Editions Inc.

287 Templemead Drive, Hamilton (ON), Canada L8W 2W4

2250 Military Road, Tonawanda, N.Y. 14150-6000 U.S.A.

www.guernicaeditions.com

Distributors:

Independent Publishers Group (IPG)

600 North Pulaski Road, Chicago IL 60624

University of Toronto Press Distribution,

5201 Dufferin Street, Toronto (ON), Canada M3H 5T8

Gazelle Book Services, White Cross Mills

High Town, Lancaster LA1 4XS U.K.

First edition.

Printed in Canada.

Legal Deposit First Quarter

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2019947082

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Title: Fish wrapped : true confessions from newsrooms past / compiled and edited by David Sherman.

Names: Sherman, David, 1951- editor.

Description: Series statement: Essential anthologies series ; 13

Identifiers: Canadiana (print) 20190160284 | Canadiana (ebook) 20190160292 | ISBN 9781771834971 (softcover) | ISBN 9781771834988 (EPUB) | ISBN 9781771834995 (Kindle)

Subjects: LCSH: Reporters and reportingCanadaAnecdotes. | LCSH: Newspaper editorsCanada Anecdotes. | LCSH: JournalismEditingAnecdotes. | LCSH: JournalismCanadaAnecdotes.

Classification: LCC PN4912 .F57 2020 | DDC 070.92/271dc23

Contents

A Grade One teacher suggested we circle the words we could read in the newspaper. So I did. And I started looking forward to the Star, waiting for it anxiously. How did they do that? Every afternoon a thick sheaf of thin paper, as wide as my arms were long, full of pictures and small print and big print and ads for food and furniture and everything else. Every day, except, of course, for Sunday. Montrealers, perhaps still in the throes of its Catholic origins, felt the day of rest was best spent praying over the worlds tribulations, not reading about them.

My father was a working man and resented paying maybe 25 cents a week for the morning paper, too. It was old news by the time he came home to the Star, his afternoon paper, already an endangered species thanks to the nascent TV news at six.

But I nagged and nagged. I soon had the Gazette to wake up to and the Star to return from school to before sitting down on the floor for the daily salt-water TV adventures of Lloyd Bridges Sea Hunt.

I never asked anyone how a newspaper was possible. I didnt know anyone privy to the magic. But I kept reading it. In a few years, I began to recognize bylines. Real people wrote this stuff, some of them from bureaus in places I found all over the globe in my bedroom Paris, London, Washington, Moscow, Tokyo, mystical foreign worlds in my struggling imagination. I began to look forward to reading them, began to understand what they were talking about.

Wrestling with these huge broadsheets became compulsive. I started reading stories on games I had seen or listened to the night before. Later, I read stories on shows I had seen the night before. How did they get this pack of paper to my door with insights on something I had seen only a handful of hours after I had seen it?

So I wrote a letter to the Star. I was 13. It was pretty on point. How does someone become a reporter? Id like to do that.

I pecked it out on my mothers Underwood, a fine machine, mailed it and forgot about it. I have no memory of if or how they replied then. But, when I finished high school, the Star did call. They had kept my letter on file. Would I like to be a copy boy in the newsroom for the summer? Are you kidding? More magic.

The Star building was nearly a block long, its front windows filled with the monstrous Goss presses and the men who made them move. They enchanted me even as a child. But, my first day on the job, five floors above, when they began to roll and the building shook, I smiled. How appropriate. Newspapers made the ground tremble, concrete and mortar shake. This was the place to be.

I dont remember a woman on the news desk. I recall only rows of white men in white shirts, bent over, scribbling and calling Copy! Not sure they ever looked at me. And, of course, they smoked, just to add to the noir of the grand white space bleached by fluorescents.

A managing editor died at his desk, they wheeled him out and the new managing editors name was painted on the door while his predecessor was still in rigor.

The mumbling police radio and its ramifications and the endless wire copy had convinced the men in the newsroom death stalked us all. Just one more obit and the question of how to play it.

I remember the composing room and hot type and hot men and sweat and fantasy. People worked like this. In the dark and noise and stink. This was how the paper was put together, in purgatory, a symphonic cacophony of regimented chaos.

I was at the wire machines when the first pictures from the moon came zipping through, line by line, in sets of three wet, coloured sheets and somehow they were going to be put together and printed downstairs and show up at everyones door next afternoon. In colour. They were in my hot little hands and came somehow via the moon. No way I could wrap my head around that. More magic.

When the summer was up they asked me to stay and work the police desk, become a reporter. But, in my family, quitting school wouldve been like dropping out of the priesthood. So I turned my back on getting paid for the best education I couldve had and went to school. The closest journalism school a curious notion was 600 kilometres away. So I stayed in Montreal, fumbled my way through a year or more of McGill and came away cherishing only the fact Ernest Hemingway admitted rewriting a single paragraph 35 times. No magic there. It was work.

Later, at the Sherbrooke Record, writing editorials, taking pictures and working the darkroom, laying out pages and learning to write, drinking too much coffee with the indefatigable editor, Jim Duff, I made an appointment with a Gazette entertainment editor. I was desperate to work on the big city daily that, under Lindsay Chrysler, had broken big stories, many by the aforementioned Mr. Duff. Before the corporation moved in and Chrysler moved on. As did Duff.