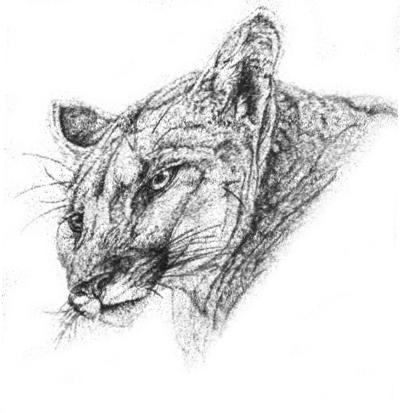

The Ghost Walker

R.D. Lawrence

The author of The Zoo That Never Was and Voyage of the Stella has produced another winning nature adventure. Lawrence decides to study the elusive mountain lion in its native habitat and spends ten months alone in the Selkirk Mountains. This is his story of survival, but also the story of the relationship that develops as he tracks a single puma to learn its habits. Sometimes he is the one being stalked, but eventually the animals come to know and trust him.

Also by R.D. Lawrence

Wildlife in Canada, 1966

The Place in the Forest, 1967

Where the Water Lilies Grow, 1968

The Poison Makers, 1969

Cry Wild, 1970

Cry Wild, Special Edition 2005

Maple Syrup, 1971

Wildlife in North America: Mammals, 1974

Wildlife in North America: Birds, 1974

Paddy, 1977

Discover Ste. Marie, 1978

The North Runner, 1979

Secret Go the Wolves, 1980

The Study of Life: A Naturalists View, 1980

The Zoo That Never Was, 1981

Voyage of the Stella, 1982

The Ghost Walker, 1983

Canadas National Parks, 1983

The Shark, 1985

In Praise of Wolves, 1986

Trans-Canada Country, 1986

The Natural History of Canada, 1988

The Natural History of Canada

Revised by Dr. Michal Polak, 2005

For the Love of Mike (Pour LAmour de Mike), 1989

Wolves, 1990

The White Puma, 1990

Trail of the Wolf, 1993

The Green Trees Beyond 1994

A Shriek in the Forest Night, 1996

Owls, the Silent Fliers, 1997

For information visit

www.crywild.com

The Ghost Walker

R.D. Lawrence

Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data

Lawrence R.D., 1921- 2003 The Ghost Walker

Originally published:

1st. ed. New York Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1983.

1. Pumas Outdoor Life British Columbia.

3. Mammals British Columbia. I. Title

[QL737.C23L38 1985] 599.7442884-23810

Copyright 1983 by R.D. Lawrence

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission except for brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Printed in Canada 2012

ISBN-978-0-9738380-0-8

Cover Drawing & Pencil Sketches - Peter McBurney

Cover & Book Design -Linda Middleton - Crystal Image Studio

ISBN 978-0-9738380-3-9 (EPUB)

ISBN 978-0-9738380-4-6 (mobi)

E-book conversion - Human Powered Design

For Kay and Ron Poulton, close friends who give comfort when needed and always welcome the wanderer on his return.

1

Sitting behind the pilot as the two seater aircraft levelled beside a snow-clad peak, I couldnt help thinking about the money I would waste if we failed to find a mountain lion within the rugged wilderness we were scrutinizing. I was fresh from a six-month sea journey and was now intent on studying this fascinating North American cat in British Columbias mountain country. But first I had to locate at least one lion in the vast hiding place that sprawled below. What were my chances?

The region I had rather arbitrarily chosen to search lies within that part of the Selkirk Range that is bounded by the northern limits of the Columbia River. This is a country of tall peaks, icefields, bare granite, and dense forests, latticed by virtually uncountable creeks that weep their icy tears down the flanks of every mountain.

Occasionally, during the start of the flight, when the pilot had to climb high to clear a majestic peak, I was afforded a view of the Columbia, which flowing northward from its Canadian source, turns abruptly at Mica Creek, then continues its journey to the Pacific Ocean, emptying itself, after having run for 1,215 miles in the estuary that divides Oregon and Washington.

As I continued to worry, the aircraft threaded between passes, flew into a valley then rose to skim over the white mountain tops that stretched from horizon to horizon, or were cloaked with mist in the far distance. The nearest ones, no more than two hundred feet away, presented a barren and desolate mien, yet were made beautiful by a pristine layer of snow or by patches of ancient blue ice that sparkled like gigantic jewels.

Forcing myself to turn my gaze from those impressive and rather intimidating peaks, I concentrated on the ground, searching it carefully with field glasses when we were flying high and with naked eyes when we descended to the lowlands. Occasionally I thrust my head out of the port or starboard windows. Since the passenger seat of this small plane was behind the pilot, I could look out both windows without having to lean across the flier. When one of the windows was open, the icy wind struck my face and made my eyes water slightly; but this was nothing compared with the blast I received when I put my head out!

When we had been searching for more than three hours without seeing a puma, I began to feel despondent. At one hundred dollars an hour, I had decided that I could afford only four hours of flying, and now the time limit was only fifty minutes away. I had seen a number of deer, a small group of woodland caribou, and two mountain goats during the first hour. Later, in one valley, I sighted six timber wolves and a large grizzly. I also saw five black bears, each in a different location.

Although the pilot was sympathetic by now, his manner indicated that he thought only a lunatic would be willing to spend so much money on the off-chance of seeing a mountain lion. Then my luck changed. The aircraft had just started to bank to port on my instruction, so I could get a better look at the terrain, when, with startling suddenness, a lithe, tawny shape emerged from a clump of young evergreens. A mountain lion! The cat raced straight across a scree slope, then stopped almost as quickly as it had appeared. Evidently, the large golden animal had been startled and probably somewhat disoriented by the droning of the aircrafts single engine.

Excited, I leaned out the Aeroncas open window and the buffeting wind almost drove one of the eyepieces of my field glasses into my eye. This made me lose sight of the cat for a moment, and when I saw it again, it had turned back toward the shelter of the trees, but now hesitated anew, undoubtedly realizing that the small evergreens offered scant cover.

Reversing itself for the second time, the lion set off at a fast run, stretching its body as its legs covered the ground, the extra-long tail, characteristic of the species, flying straight out behind, its black tip bobbing slightly as the animal dashed over the treacherous rock fragments and sent small and dusty avalanches rolling downhill. The pilot, obeying my shouted instructions, tipped the small twin-seater to the right, giving me a better view of the speeding cat.

From three hundred feet up, I had an almost perfect view of the animal. Its ears were pressed back against its round head and its muscles and sinews moved rhythmically, alternately bunching and relaxing while its low-hung belly brushed over some of the larger stones on the lower flank of the mountain. Twice the puma looked upward and sideways before it reached the shelter of the tall trees that hid it from my sight, but although I had been given but a few seconds in which to watch the big cat, I was more than satisfied and content as the pilot levelled the Aeronca and I pulled my head back into the cabin. I would naturally have enjoyed watching the lion for a longer time, but the sight of it, however brief, had concluded to my satisfaction the first stage of my expedition.

![Lawrence Durrell [Lawrence Durrell] - Caesar’s Vast Ghost](/uploads/posts/book/142113/thumbs/lawrence-durrell-lawrence-durrell-caesar-s.jpg)