Preface

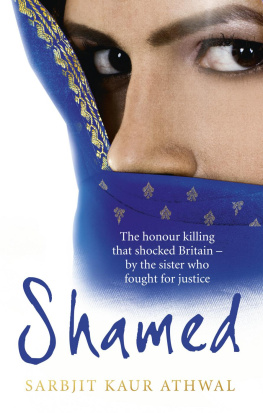

The first time I encountered an honour killing was in 2004, in a village near Meham, in the heartland of Haryana. A girl had been done to death by her father and brothers for eloping with a boy from a neighbouring village. When I went to her house, I found that the only one who was grieving for the girl and even prepared to say that she had been killed was her mother. The woman, who had probably seen her little girl being throttled to death, was distraught, but lacked the courage to defy her family and walk up to the police station two kilometres away to lodge a complaint.

She found in me a ready punching bag to vent an impotent fury. Where were you when my girl was being killed? Where were all these questions that you are directing at me now? I was confronted with the typical dilemma of a reporter: of how far I should probe to uncover the crime, knowing that it would mean scraping at layers of her still-raw wounds. Her raging helplessness remained with me for a long time, as I subsequently covered many more such incidents over the years.

With North India as my beat in Outlookthe weekly newsmagazine where I worked, till recentlyI travelled extensively through Haryana, western Uttar Pradesh and Punjab, documenting cases, analysing causes and seeking countless opinions as I tried to comprehend the problem. Then, just when I thought I had explored the modern-day recurrence and spread of honour crimes from every possible angle, I received a call from Kamini Mahadevan of Penguin Books India.

She wanted me to do a book on honour killings and my first impulse was to refuse. What else could I possibly write on the subject? I had already written everything I knew in my articles, and to churn out another 70,000 words seemed quite impossible. Besides, how would I find the time for it? I already had my hands full, covering four states for Outlook. I discussed the offer with Ajith Pillai, the then senior editor at the magazine, who urged me to take it. He told me that I could do the research for the book along with my routine reporting and take a few months off to pen the manuscript. The next step was to convince Vinod Mehta, my editor, to give me leave for a few months towards the end. He readily agreed and now I really had no reason to dither.

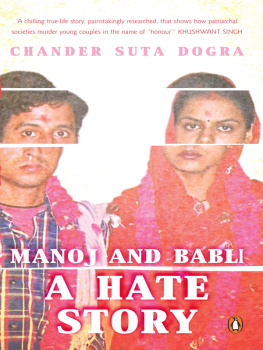

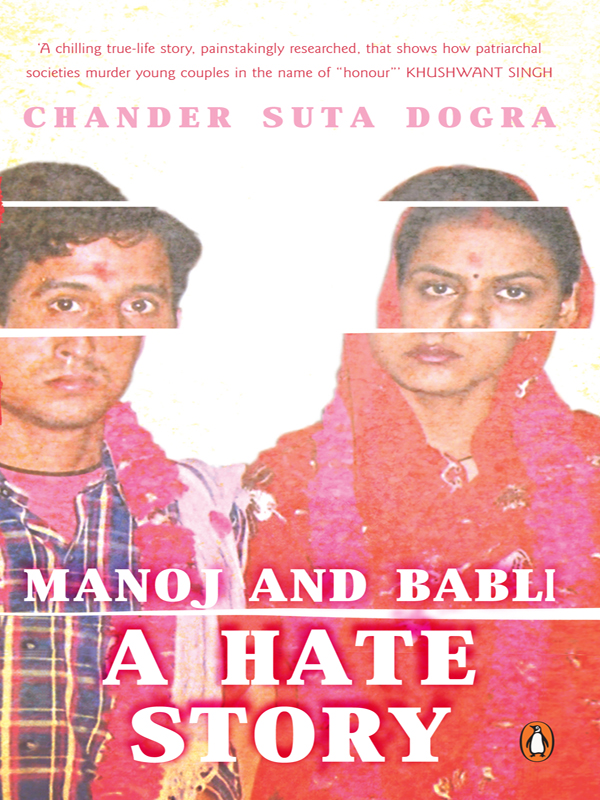

This was in 2010, the year a sessions court in Karnal had delivered a landmark judgement in the well-known ManojBabli honour killing. For the first time, a court had sentenced to death those accused of killing for the sake of honour. I completely missed reporting on this important development because I was doing stories from other states the month the judgement came. By the time I returned to Haryana, newspapers had finished doing editorials on the judgement. Perhaps it was ordained that I would approach this case more comprehensively because the more I looked at this story, the more I realized that it should be my book. That, in hindsight, was the easy part.

*

Haryana is not a reporters delight. It is hard to ferret out information here and at the best of times villagers can be taciturn, even suspicious of outsiders asking questions. You could be asking for serious trouble if you happen to pry into their social customs and traditions, especially something touchy like honour crimes. It took me about a year to research this book. From establishing contact with the families of Manoj and Babli, the couple who was killed for marrying into the same gotra, or sub-caste, to getting into the minds of khap leaders in order to understand their motivations.

The more I dug into the story, the more I realized that it was really the heroic struggle of two women, Seema and Chandrapati, who fought against debilitating odds to bring those responsible for the deaths of this young couple to justice. Both the women shared their hopes and struggles, their hardship and fears with me in person and in countless late-night phone conversations (which I continue to have with them). Late night, because that is the only time they can spare for lengthy recollections of their journey.

Seema, Manojs sister, is a constable with the Haryana police, presently posted in the Madhuban police academy, and has a security cover at all times. She told me over the phone that if I wanted to meet her at the academy, where she has a small government flat, I would need permission from her superiors. I worked the channels from the office of the director general of police (DGP) downwards but the police officers would not let me meet her there. We eventually worked out a system. She would tell me when she was going to her village, Karoran, for the weekend and I would drive down from Chandigarh to meet the family.

I always visited during the afternoon siesta, when few people are about. I took care not to go to Chandrapatis house directly. The caution was rooted in my first experience of the village when I ran into a mixed bunch of young and old men playing cards under a tree. I had sought to draw them into a conversation about the honour killing that had taken place in their village, but was curtly put in my place. Behenji, ask us anything else about the village, but not about this case. Its a matter of our village honour and we are not prepared to discuss it with you, they said. Just like that. A deadpan delivery, tinged with menace. I changed tack and asked for the sarpanch. Accompanied by the sarpanchs mother, I made my way to the house of Babli, hoping to speak to her mother, Ompati. She was plainly hostile: she all but threw me out of her house, warning me never to come there again.

I was also unable to meet the men lodged in Ambala jail, convicted by the courts for the killings, mainly because no official wanted to take the risk of allowing me to meet them. The convicts, who had once been feted across the state for upholding community honour, are today living an ignominious life in jail. It is a sore point with community leaders, and officials are wary of doing anything that can upset the dominant caste. So my requests to officers in the chief ministers office and downwards, till the Ambala district administration, were politely ignored.

I did, however, get lucky with Gangaraj, a Congress worker, widely believed to be the mastermind behind the crime, who was convicted by the Karnal court but subsequently acquitted by the Punjab and Haryana High Court for want of sufficient evidence. He had just returned to Karoran after doing three years in jail, and once again I routed my request to meet him through the sarpanch. I was in luck. Gangaraj, who has refused to meet any journalist after being released from jail, agreed to meet me. But no tape recorders. I could have refused and said I am not at home. So dont record this conversation, he said to me. The man whose activities had held all of Haryana in thrall for almost two years told me that he has given up politics because the party had not stood by him. He was bitter and withdrawn. While researching Gangaraj, I chanced upon two videos taken by the local stringer of CNN-IBN, a national channel, which featured the man.