Copyright Nicholas Faith, 2013

The right of Nicholas Faith to be identified as the author of this book has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

First published in 2013 by

Infinite Ideas Limited

36 St Giles

Oxford

OX1 3LD

United Kingdom

www.infideas.com

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of small passages for the purposes of criticism or review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except under the terms of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP, UK, without the permission in writing of the publisher. Requests to the publisher should be addressed to the Permissions Department, Infinite Ideas Limited, 36 St Giles, Oxford, OX1 3LD, UK, or faxed to +44 (0) 1865 514777.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 9781909652477

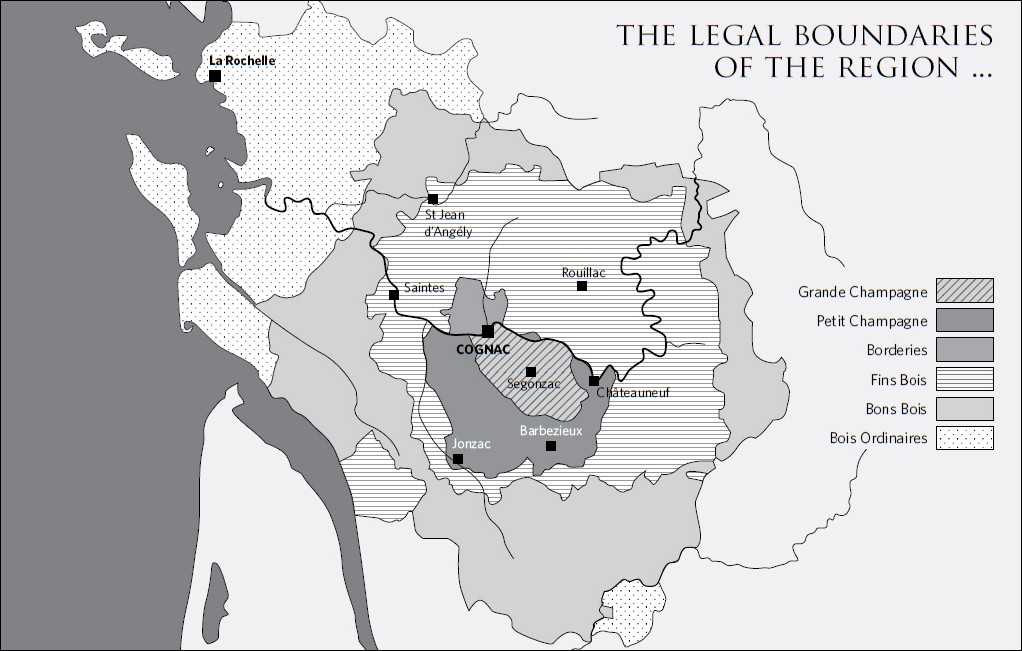

Front cover photo and plate 3 BNIC/Jean-Yves Boyer

Illustrations on pages 8, 21, 32, 40 and 112 courtesy of Courvoisier/Beam Global/Anne Cochet Back cover, bottom, photographs on pages 16, 17, 47, 198 and plates 4, 5 (top), 6, 7, 8 BNIC/Stphane Charbeau

Photographs on pages 18, 31, 36, 41, 42 (Pierrette Trichet), 106 and 122 courtesy of Rmy Martin Photograph on page 20 courtesy of Hine

Back cover, top row, photographs on pages 29, 42 (Yann Fillioux), 73, 74, 81, 118, 147 and plate 1 courtesy of Hennessy

Photograph on page 43 (Patrice Pinet) courtesy of Courvoisier/Beam Global

Photograph on page 108 courtesy of Frapin/McKinley Vintners

Photographs on pages 43 (Benoit Fil), 68, 97 courtesy of Martell

Plate 2 BNIC/Grard Martron

Photo of author by Jean-Luc Garde

Text designed and typeset by Nicki Averill Design

Printed in Great Britain

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thirty years ago my old friend Michael Longhurst suggested that I should write a book about cognac, a suggestion I accepted and have never regretted. Since then I have been able to rely on many friends, old and new, to produce this third and thoroughly revised edition. In no particular order they include David Baker, Alain Braastad who has forgotten more about cognac than I will ever know Bernard Hine, Colin Campbell, Alfred Tesseron, Georges Clot, David Baker, Benoit Fil, Patrick Leger, Olivier Paultes, Yann Fillioux, Olivier Blanc, Pierre and Jennifer Szersnovicz, Catherine Mousnier, and Catherine Lepage, Agnes Aubin, Laurine Caute at the BNIC, Stephane Feuillet, Luc Lurton at the Station Viticole, Michel and Catherine Guillard who have let me stay in their lovely house so often, as well as my former colleagues at the International Spirits Challenge, most obviously Simon Palmer and Neil Mathieson.

Thanks also to Richard Burton, Rebecca Clare and their so agreeable and professional colleagues at Infinite Ideas.

INTRODUCTION

THE UNIQUENESS OF COGNAC

In winter you can tell you are in cognac country when you turn off the N10, the old road between Bordeaux and Paris at the little town of Barbezieux and head towards Cognac. The landscape does not change dramatically; it is more rounded, perhaps a little more hilly, than on the road north from Bordeaux, and the vines are thicker on the ground. But the major indicator has nothing to do with the sense of sight. It has to do with the sense of smell. During the distillation season from November to March the whole night-time atmosphere is suffused with an unmistakable aroma, a warm smell that is rich, grapey, almost palpable. It emanates from dozens of otherwise unremarkable groups of farm buildings, distinguished only by the lights burning as the new brandy is distilled.

Cognac emerges from the gleaming copper stills in thin, transparent trickles, tasting harsh and oily, raw yet recognisably the product of the vine. If anything, it resembles grappa; but what for the Italians is a saleable spirit is merely an intermediate product for the Cognacais. Before they consider it ready for market it has to be matured in oak casks. Most of the spirits, described by the more poetically minded locals as sleeping beauties, are destined to be awakened within a few years and sold off as relatively ordinary cognacs, but a small percentage are left to sleep for much longer. Every year expert palates sample them and eliminate or, rather, set aside for immediate sale those deemed incapable of further improvement. As the survivors from this rigorous selection process mature, so their alcoholic strength diminishes and within forty or fifty years is down from around 70 to 40 per cent the strength at which cognacs, old and new, are put on the market. These truly aristocratic brandies are then transferred to the glass jars damejeannes, known to the Cognacais as bonbonnes each holding 25 litres of the precious fluid, and stored, even more reverently, in the innermost recesses of their owners cellars the aptly named paradis familiar to every visitor to Cognac.

Hennessy has the biggest paradis in Cognac itself, but an even more impressive collection is hidden away in the crypt of the medieval church of the small town of Chteauneuf sur Charente, a few miles to the east. The Tesseron family store their brandies in this holy cellar. For nearly a century four generations have supplied even the most fastidious of the cognac houses with at least a proportion of the brandies they require for their finest, oldest blends. The Tesserons two paradis contain over 1,000 bonbonnes dating back to the early nineteenth century. I was privileged to taste a sample of the 1853 vintage.

The world of cognac is governed by certain immutable rituals. Even when pouring the 1853, the firms matre de chai swilled out the empty glass with a little of the cognac and dashed the precious liquid to the floor to ensure that the glass was free from impurities. Astonishingly, my first impression of the cognac was of its youth, its freshness. Anyone whose idea of the life-span of an alcoholic beverage is derived from wines is instinctively prepared for the tell-tale signs of old age, for old wines are inevitably faded, brown, their bouquet and taste an evanescent experience. By contrast even the oldest cognacs can retain their youthful virility, their attack. It seemed absurd: the brandy was distilled when Queen Victoria was still young, and the grapes came from vines some of which had been planted before the French Revolution. Yet it was no mere historical relic but vibrantly alive. But then the perfect balance of such a venerable brandy is compounded of a series of paradoxes: the spirit is old in years but youthful in every other respect; it is rich but not sweet; deep in taste though relatively light, a translucent chestnut in colour. Its taste is quite simply the essence of grapiness, without any hint of the over-ripeness that mars lesser beverages.

But what makes cognac the worlds greatest spirit, is not only its capacity to age but its sheer complexity. When the BNIC convened a hundred of the worlds leading professionals in early 2009 to discuss the individual tastes associated with the spirit they came up with over sixty adjectives shown in the Cognac Aroma Wheel on page 150 to describe cognacs of every age, from the overtones of roses and vine flowers of the young to the leatheriness and nuttiness obvious in the oldest brandies.

Next page